In Ireland, supermarket shelves are dominated by two kinds of butter: conventional dairy-based butter or plant-based vegan butter that’s made from palm oil. It was frustrating to see that almost every store that I checked – Lidl, Aldi, Tesco, and Marks & Spencer – only stocked products from these two categories. I searched widely and eventually found two plant-based butters that are palm oil free – I’ll get to them later. Before that, I want to explain why the first two options are not ideal.

Dairy butter is not an ideal choice for a number of reasons. There are the ethical issues with dairy farming that I outlined in my previous post. If you’re not familiar with the less humane aspects of dairy, which are almost universal in the industry, then take a look at that post. There are other animal welfare issues that vary from farm to farm – such as the raising of dairy cows in year-round indoor feedlots, common in Europe but also creeping into Ireland now too.

Vegan butter that’s made from palm oil avoids the animal welfare issues of dairy farming, but it has other ethical issues, related to palm oil, which you’re probably aware of to some extent. Is a spread made from palm oil (which may result in the destruction of rainforest habitats and high CO2 emissions from the burning of peatland) an acceptable substitute for dairy? Does RSPO certification guarantee that these destructive practices don’t take place? Let’s take a quick look before moving on to the best option of palm-oil-free vegan butters.

Carbon Footprint: Dairy vs vegan butter

Dairy typically has a significantly larger carbon footprint than plant-based butter and also larger footprints for land use, water use, and nitrogen and phosphorus pollution, depending on the situation. Here are a couple of specific examples of life cycle assessments (LCAs) that compare the carbon footprint of a plant-based butter to dairy butter.

Miyoko’s cultured vegan butter vs dairy butter

An LCA was conducted for Miyoko’s (my favorite plant-based butter) with the carbon footprints for dairy butter and Miyiko’s butter calculated to be 20.5 kg and 1 kg of CO2 equivalents, respectively, per kg of product. So Miyoko’s, which is made primarily from organic coconut oil and organic cashew milk, has a carbon footprint around 20 times lower than that of butter. Perhaps 12 times lower is a more realistic number, based on other assessments of the carbon footprint of dairy butter. That’s still a huge difference.

Upfield’s plant-based spreads (e.g., Flora) vs dairy butter

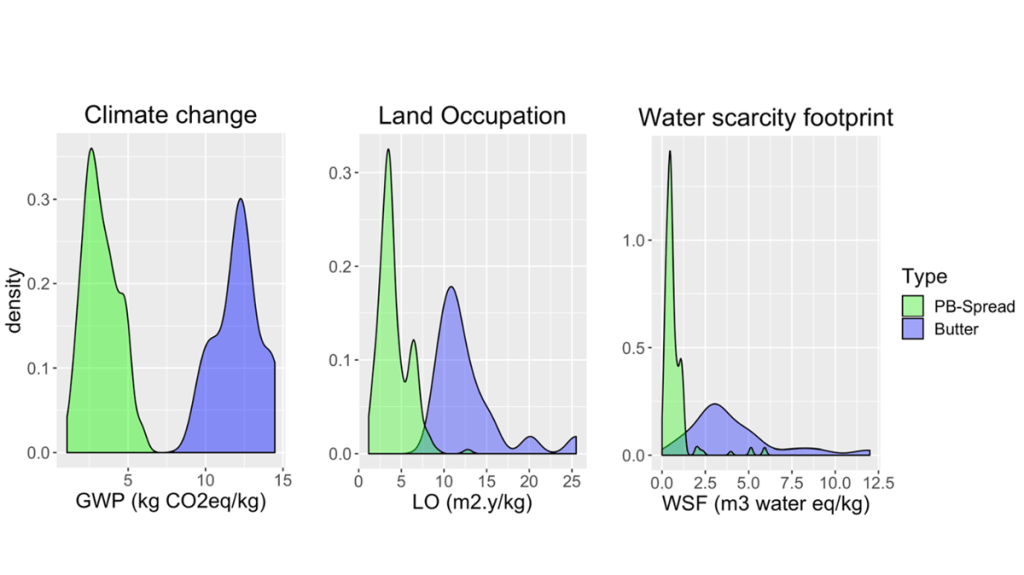

An LCA comparing all of Upfield’s plant-based butter products (such as Flora) to dairy butter was published in a peer reviewed journal in 2020. The carbon footprint for the 212 plant-based spreads sold by Upfield around the world ranged from 0.98 to 6.93 kg of CO2 equivalents per kg of product, with an average value of 3.3. The carbon footprint of the dairy butter products ranged from 8.08 to 16.93 kg of CO2 equivalents per kg of product, with an average value of 12.1. So, the average Upfield plant-based butter had a carbon footprint almost four times lower than that of butter. But the worst Upfield spread had a carbon footprint of around 7 kg CO2, which is pretty close to the footprint of the best butter spread, 8 kg CO2.

Why are some plant-based spreads worse than others? It’s mainly due to the impact of the agricultural methods used to grow the product’s ingredients. A large portion of the impact is often due to specific ingredients such as palm oil that are responsible for deforestation, or some other form of land use change.

Palm oil, land use change, and climate change

In my post on the latest IPCC report, from working group 3, I showed the following breakdown of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by sector:

Industry – 34%

Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) – 22%

Buildings – 16%

Transport – 15%

Energy supply sector – 12%

Here’s the shocking fact: about half of the emissions from AFOLU are specifically from land use change, predominantly from deforestation. That’s about 11% of global GHG emissions! Compare that to air travel, which is responsible for 2.5% of global GHG emissions.

This is a critical reason why I avoid palm oil, along with others that I outlined in a post on why is palm oil bad? But it’s also a reason why we need to be conscious of where certain products come from, like soybeans. I found the chart below to be very useful – it’s from the same 2020 paper. The length of each bar represents the carbon footprint (kg of CO2 equivalents per kg of product) of each oil/butter with the black part of each bar showing the portion of the footprint that’s due to land use change (LUC).

You can see that soybean oil has a low footprint, except when sourced from Brazil (BR) where there’s a large impact from land use change (i.e., impact on the Amazon rainforest). Palm oil from Indonesia (ID) also has a high carbon footprint due to land use change (deforestation, burning of peatland). Better options include rapeseed oil (also known as Canola) from most countries and olive oil.

I think we have to treat this data with some caution, particularly as some of the authors work for Upfield, which uses considerable amounts of palm oil in its products. The data that I checked are generally in line with values that I’ve found in other studies, but in the case of palm oil it’s quite likely that the carbon footprint has been underestimated. Upfield provide the following statement on palm oil sourcing on flora.com:

Flora buys 100% sustainable palm. As a responsible brand, we’re committed to ensuring that the palm oil in Flora is from sources that respect human rights, cause no deforestation or climate change impacts with public acknowledgement by NGOs. Upfield is a proud member of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO).

Does RSPO certification ensure that palm oil is sustainable?

The RSPO scheme has been widely criticized for being ineffective. A 2018 paper on the effectiveness of palm oil certification in achieving sustainability objectives found that:

Using Indonesian [palm oil] as a case study, a novel dataset of RSPO concessions was developed and causal analysis methodologies employed to evaluate the environmental, social and economic sustainability of the industry. No significant difference was found between certified and non-certified plantations for any of the sustainability metrics investigated

I just re-read that paper and actually the RSPO-certified areas look worse than the conventional palm oil in terms of orangutan population density.

I like to give programs a time to work out kinks, and there are probably some upsides to RSPO-certified palm oil, particularly when certification is at the highest level: identity-preserved. Researchers from Aalborg University, Denmark, published findings in 2020 that the carbon footprint of palm oil is around 35% lower when RSPO-certified.

However, it seems to me that any improvements in RSPO standard are not coming fast enough, considering that this decade is absolutely crunch time for dealing with climate change and habitat destruction.

Bottom line on palm oil spreads

You may be able to argue that spreads made from palm oil are a bit better than butter, from an ethical perspective. Upfield’s palm oil, used in a lot of it’s plant-based spreads (Flora, Blue Band, Country Crock, and many other brands) is certified at the RSPO segregated or mass balance (mixed) levels. That’s a step above Conagra’s Earth Balance, which is certified mostly at the lowest level (Palm Trace credits) but below RSPO’s top level (identity-preserved) and far from Nutiva (Palm Done Right) which is one of the few brands I trust for palm oil.

If you can manage to find one, I recommend switching to a plant butter that’s palm oil free.

After a good bit of searching, I found two of these in Ireland. There may be more in bigger stores, but the two that I found are both stocked in Dunnes Stores and my local health food shop:

- Naturli’ Organic Vegan Block

- Dairygold Plant-based Butter

Both of these work well as butter but from a sustainability perspective I particularly recommend Naturli’ vegan block. I’ve written a post all about this product on my other site, Ethical Bargains, discussing taste (compared to Dairygold, Flora, and others) and sustainability. Interestingly, the main ingredient is organic shea butter from Ghana. Read more here:

Thanks for yet another informative post. Sad to say, my plant-based vegan butter contains palm oil in addition to canola and olive oils. Time for a change.

LikeLike

Hey Rosaliene!

I recommend trying Miyoko’s butter if you haven’t already – here’s a review on my other site:

Since you’re in CA, you can often find it on discount at the Grocery Outlet. It’s also fairly affordable at Trader Joe’s.

Cheers!

J

LikeLike

Thanks for the recommendation. I’ll check it out.

LikeLike

Thanks, James. I’ll see if I can find these in my grocery. Between palm oil and beef, it’s a wonder we have any rain forests left!

LikeLike

Hey Pam! These brands are mostly sold in Europe market, except for Miyoko’s vegan butter, which is available in the US.

Let me know if you’d like to evaluate a brand – you can enter the Green Stars contest and win a subscription to Ethical Consumer!

LikeLike

Ever since I heard years ago that margarine – which was supposed to be more heart healthy than butter – was basically plastic I think I just checked out of the whole thing. I don’t use much butter and don’t even cook much with it, preferring olive, avocado and other oils for most things but cows do contribute greatly to climate change so perhaps it’s time to investigate, James. When I do I will share my results.🤔🙏

LikeLike