In the last post I covered third-party certifications for compostable items, and also addressed some of the common criticisms of compostable materials. The upshot: when compostable materials are certified by a reputable third-party organization, it avoids many of their perceived problems (confusion over sorting, presence of PFAS).

There’s still the argument that compostables distract from a much needed move back to reusable items. This is valid in some circumstances but it’s naïve to think that plastics don’t need improvement because they will just go away.

For sure, we should adopt good habits like carrying a personal water bottle and/or coffee mug, or asking folk to bring their own utensils for the birthday cake at the office. However, there are many situations where some kind of plastic is needed (or at least is not going away soon) so we need a more circular alternative.

As discussed in a recent post, the plastics industry is one of the fastest growing manufacturing sectors and already has a larger carbon footprint than global air travel. If its growth continues on course, plastics production would account for 25-33% of the IPCC’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions budget for 2050.

This GHG data alone should be enough to convince anybody that change is badly needed, both in our consumption habits and the plastics industry. There’s so much focus on pollution from plastics that the carbon footprint is often overlooked. This footprint can only be reduced by decreasing the total amount of plastic produced and/or developing new materials with a lower footprint.

This brings us to a point about compostable materials: a comparison to petrochemical-based plastics is not just about the end-of-life but also the environmental footprints of manufacturing them. So let’s start at the beginning.

Are compostable plastics better by design?

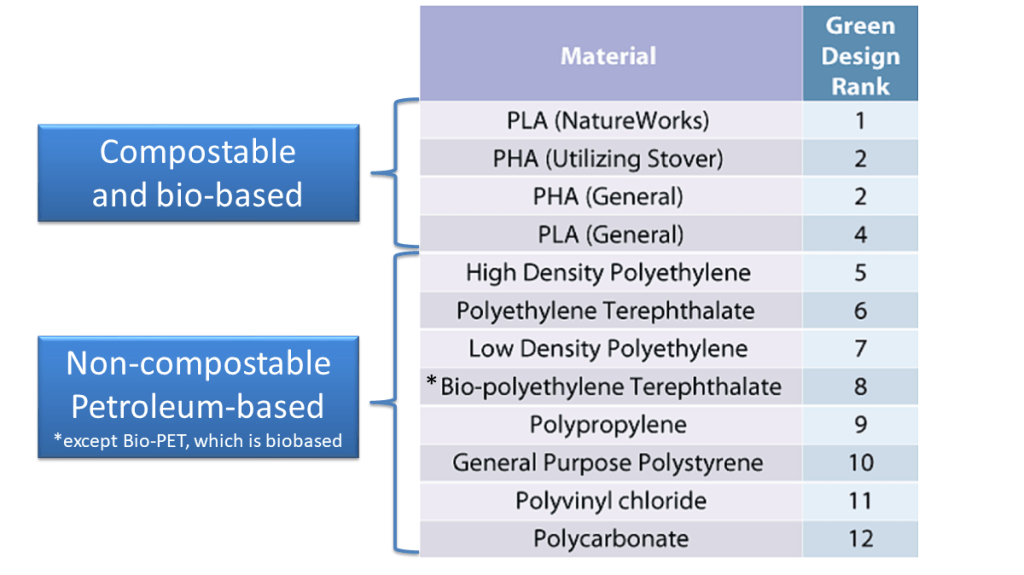

Researchers from the University of Pittsburgh analyzed the environmental impacts of the most commonly used plastics, both bio-based and petroleum-based polymers. The term “bio-based” refers to plastics that are made mainly from renewable materials (i.e., plant-based), including some compostable plastics and also some regular (recyclable) plastics.

The authors included three kinds of bio-based plastics in their analysis. Two of them, polylactic acid (PLA) and polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA), are compostable while the third one, Bio-PET, is not. Bio-PET is chemically the same as the regular PET (polyethylene terephthalate) that’s used to make most plastic water/soda bottles – it’s just made partly from plant-derived chemicals instead of petrochemicals. See the previous post on certifications for compostables for more on bio-based plastics.

The compostable plastics, PLA and PHA ranked highest among all plastics in terms of green design principles – which are a set of green chemistry and green engineering principles for more sustainable design (e.g., the use of renewable feedstocks, safer chemicals, energy efficiency, and design for end of life). The Bio-PET did not do so well in the green design ranking but future improvements to the production process are possible.

The carbon footprint of compostable plastics

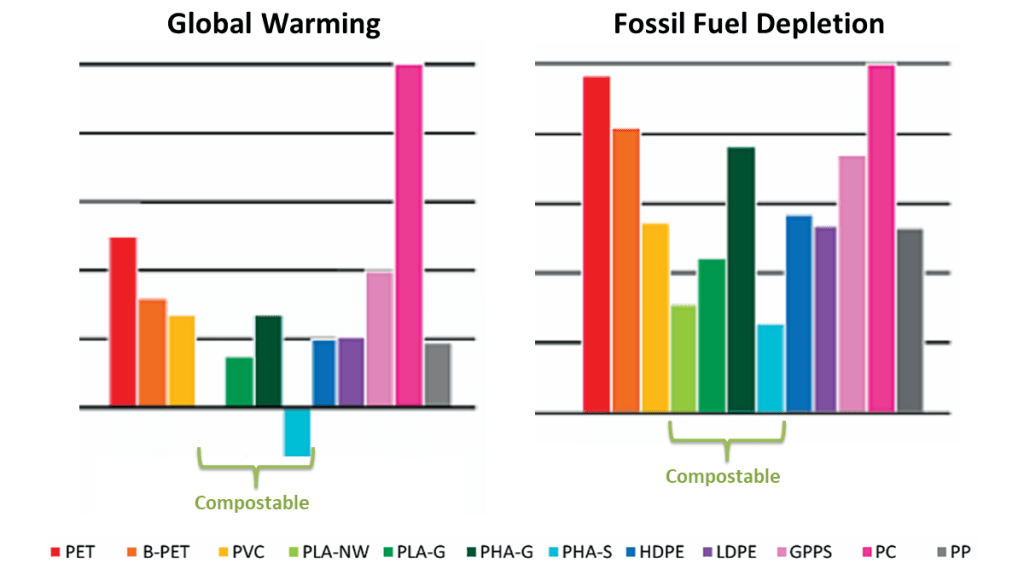

The data above indicates that the bio-based compostable plastics are better in principle. How about in practice? Below is a detail from the same paper showing estimates for the carbon footprint (global warming potential) and fossil fuel usage for making the same set of plastics.

Again, the compostable plastics, PLA and PHA are among the best options when it comes to reducing the carbon footprint of plastics. The exact size of these footprints depends on how the compostable plastics are made.

For example, the general process to make PLA (PLA-G in the charts above) has been improved by a major PLA producer, Nature-Works, bringing significant reductions in fossil fuel usage and carbon footprint (PLA-NW, above). Both versions of PLA are better than all petrochemical-based plastics on these climate-related metrics and in fact the Nature Works process is approaching carbon-neutrality. Nature Works has also published a series of life cycle assessments (LCAs) of their PLA product in peer-reviewed journals (2007, 2010, and 2015) showing a 70% reduction in carbon footprint over this time. This kind of reduction is unlikely to occur with petrochemical-derived plastics.

Let’s look at the data for the other major compostable plastic, PHA. Two routes for the production of PHA were considered in the figure above – from sugars derived from corn grain (PHA-G) or from corn stalks (PHA-S). Making PHA (or PLA) from corn stalks or other agricultural byproducts would bring large reductions in carbon footprint – the trick is to make this process economically feasible.

There are direct parallels to the replacement of fossil fuels with biofuels. The first generation of biofuels was dominated by ethanol made from sugars (corn grain in the US, sugarcane in Brazil). But the goal then became to move beyond sugars and start using cellulose-based feedstocks such as corn or rice stalks. It’s all technically doable but the difficult part is to make it competitive with the price of petroleum.

It seems that some of the bio-based compostable plastics are already ahead of biofuels, when it comes to competing with petrochemical-based products. Further improvements will come over time, perhaps even reaching the carbon-negative status of PHA made from agricultural waste like corn stover (PHA-S in the figure above).

To me, this demonstrates the potential for bio-based materials such as the compostable polymers PLA and PHA. The plastics industry can be converted from a major climate change threat to a fairly circular low-carbon industry.

Is it okay to landfill compostable materials?

A study from Nature Works addresses one of the concerns with compostable materials such as PLA: What happens if we send it to landfill instead of compost facility? The trials demonstrated that PLA is unlikely to generate any methane if disposed of in a landfill, under normal conditions.

Some argue that, when sent to landfill, PLA is a form of carbon capture and storage – CO2 that’s captured by plants is converted to PLA and then stored in landfill. However, another study disputes this, suggesting that if landfill temperatures become elevated (to 55°C, above the normal operating limit), PLA can degrade, resulting in methane production.

Considering all of this (and acknowledging that there’s some uncertainty here) I think certified compostable plastics like PLA should be disposed of in your green waste bin for industrial composting. Here’s another reason:

Compostables help prevent sending food waste to landfill

Some of the best uses for compostable materials are when they help prevent food waste going to landfill (food sent to landfill is likely to lead to methane generation). Examples include compostable tea bags, coffee filters, compostable waste bags, and some kinds of food packaging. There are also several scenarios where compostable food trays, cups, and utensils make sense: closed situations like music festivals or work canteens where food waste and containers can be collected together as compostable waste.

Often when food is packaged in recyclable packaging – a frozen dinner in a polypropylene tray or a take-out pizza in a cardboard box – the material is not suitable for recycling in the end. When you’re in doubt (a food-encrusted frozen dinner tray or greasy pizza box) it’s better to put it in the landfill waste (dinner tray) or green waste (pizza box) rather than risk contaminating recycling waste streams. Compostable packaging can help avoid these situations as it doesn’t matter that it’s food-encrusted when you put it in your green waste bin – even better, in fact!

Bottom line on compostable plastics

Compostable plastics are not perfect across all environmental metrics but they are better than petrochemical-based plastics in the critical categories of carbon footprint and fossil fuel usage. On the basis of this, and the other factors discussed above, I support compostable plastics as one of the better options. I’m not saying that we should go crazy on disposables just because they are compostable (Again, carry a reusable water bottle and coffee mug!) because it’s not a zero-consequence material.

Compostable plastics are better in principle (the green design ranking, shown above) and it’s often best to back the options that are better in principle, even if not perfect yet. There’s a pretty high likelihood that further improvements will come: tweaks to materials, production methods, and waste systems. The recycling of PLA would offer additional environmental benefits – it’s not yet an option but would be a good long term goal (and we need to think long term).

The arguments for compostables like PLA and PHA become even stronger when you add in the end-of-life considerations – the fact that compostable plastics can decompose, completing a biological cycle. Plus, they can help avoid sending food waste to landfill, where it can generate methane. Just make sure to check that the items you are thinking of buying or throwing in your green waste bin are certified compostable.

Green Stars ratings for compostable products

In the early days of the Green Stars Project I reviewed and compared three brands of compostable plastic bag: If You Care, World Centric, and BioBag. I’ll revisit this topic when I get around to my reboot of the ethical shopping guide, but long-story short, all three of these brands score well (4 to 5 Green Stars).

On Ethical Bargains, I’ve covered Alter Eco truffles, which come in compostable wrappers, and Earthbound Farm greens, which now come in a recyclable cardboard tray that’s in the process of being certified compostable. When I see a food item in compostable packaging, I think of it as a definite plus.

Discover more from The Green Stars Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The human race is good at creating harmful, difficult problems. That’s an understatement.

LikeLike

Thanks for this deeper dive, James. I often wonder if we aren’t substituting one problem for another such as when corporations say “here’s the fix.” I’m particularly thinking of PFAS — replacing PFOA with GenX as the safer alternative, only to later read a study that said it was worse for marine life. So often, corporations hide the real threat, hoping to squeeze a few years of profit out of the fix that it makes my head spin trying to keep up. Your blog definitely helps suss it all out. Kudos to you for continuing this important work.

LikeLike

Great helpful post! I think we could use a lot more glass like we used to have.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes indeed. Is also just nicer when food products like peanut butter or jam come in glass jars rather than plastic

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great and informative overview of compostable materials and their environmental benefits! 🌍

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike