A recent post examined the carbon footprint of the beef industry and compared it to the footprints of steel and cement production. Here’s a quick summary:

We produce massive amounts of cement and steel, worldwide, and they each account for 6-7% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. But the carbon footprint of beef production is actually as high as the other two, even though far less beef is produced, globally. This is because the carbon footprint per kilogram of beef is exceptionally high: 100 kg CO2 equivalents (CO2eq) per kg of beef.

There’s an update on that number, which I want to focus on here. The data above on the carbon footprint of beef comes from a seminal paper, published 2018, on the environmental footprints of food. One year later, the authors, Oxford University scientists Poore and Nemecek, issued a correction (erratum) that included vital new information.

The correction described an adjustment to the carbon footprint of animal products. In the original paper the authors had discussed how a vast amount of land would be freed up if we are less meat. But they had not recognized quite how much atmospheric CO2 could be captured on that land, once repurposed or rewilded.

Let’s take a look at the authors’ words:

Erratum to Poore and Nemecek (2018)

Corrections to Poore and Nemecek’s paper, Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers, were published in early 2019. Here’s a key conclusion from the original paper:

Moving from current diets to a diet that excludes animal products has transformative potential, reducing … GHG emissions by 6.6 billion metric tons of CO2eq.

The erratum added this:

In addition to the reduction in food’s annual GHG emissions, the land no longer required for [the production of animal products] could remove ~8.1 billion metric tons of CO2 from the atmosphere each year over 100 years as natural vegetation re-establishes and soil carbon re-accumulates.

Let’s put that into perspective: the total annual reduction in GHGs that would come from excluding animal products in our diets is 6.6 + 8.1 = 14.7 billion tonnes of CO2eq. That’s a 28% reduction in global GHGs.

(Global GHG emissions are stated in the paper as 52.3 billion tonnes of CO2eq, using 2010 as a reference year).

Factoring in carbon sequestration by the soil and vegetation is a huge deal: to have an 8.1 billion tonne reduction in GHGs every year for 100 years! (And then there are the benefits of returning of a huge chunk of the earth to nature.)

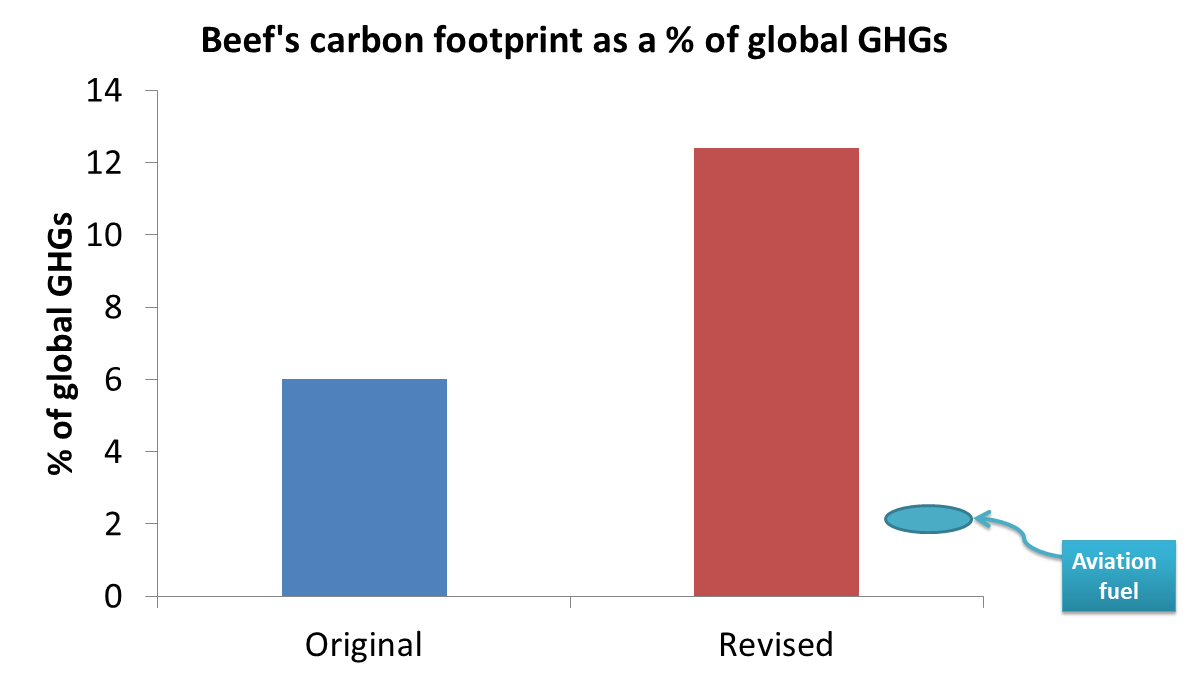

Here’s a little more perspective – think of all of the people working on sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) as a climate solution. That is important work, with aviation fuel responsible for around 2.5% of GHGs – but that’s less than a tenth of GHGs from animal products.

The impact of land footprint on carbon footprint

This revision to the climate impact of meat production comes down to the industry’s huge land footprint. Here’s Poore and Nemecek’s conclusion on the land impact of animal products:

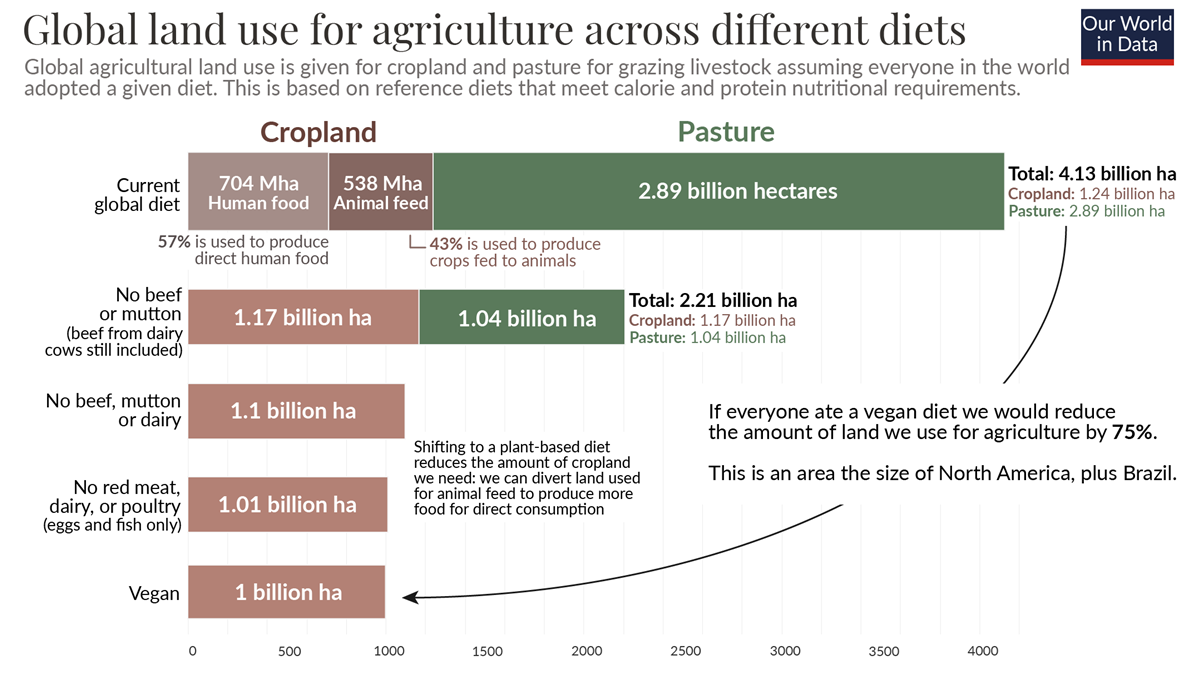

Moving from current diets to a diet that excludes animal products has transformative potential, reducing food’s land use by 3.1 billion ha (a 76% reduction)

Three quarters of the land currently used for food production (arable and grazing land) would become free for rewilding, reforestation, recreation, or whatever we wanted, if we all adopted vegan diets.

The shift in diet would also shift our status on several of the nine planetary boundaries out of the high-risk zone, or at least bring us closer to the safety zone. Poore and Nemecek provide data on meat’s contribution to five of these boundaries: GHGs, land use, acidification, eutrophication and water scarcity.

However, the whole world is unlikely to go vegan overnight, so let’s zone in on a realistic target: the animal product with by far the biggest carbon footprint. Based on Poore and Nemecek’s data, I’ll estimate how much of the 8.1 billion tonnes of GHGs sequestered in repurposed land could come from eliminating just that one item: beef.

The land footprint of beef

Beef production takes up a huge amount of agricultural land, either for direct grazing or to grow cattle feed. Take a look at the chart below on the land footprint of key foods that we consume for protein. Food products that come from ruminants have the largest land footprints – beef (from a beef herd) and lamb in particular, followed by cheese.

A revised carbon footprint for beef

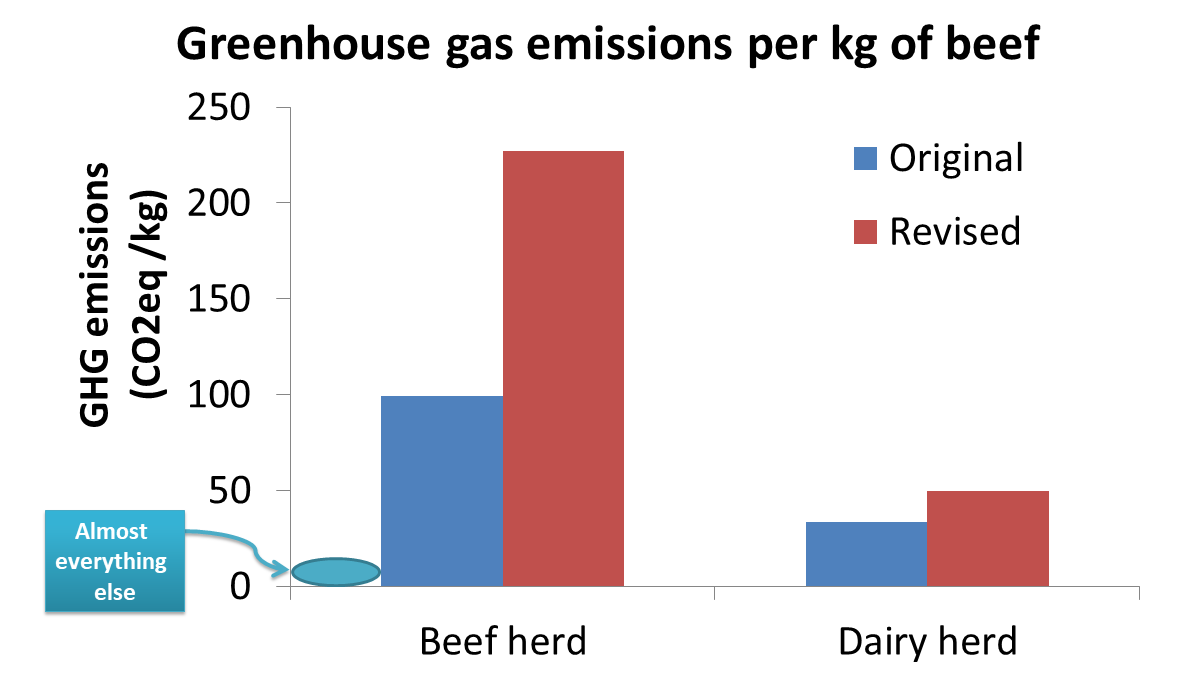

So the commonly accepted carbon footprint of 1 kg of beef was 100 kg CO2eq if the beef comes from a beef herd (e.g., steak cuts, Angus burger, etc.) and 34 CO2eq if it comes from a dairy herd. That’s from Poore and Nemecek’s 2018 paper.

Let’s factor in the data from the authors’ 2019 correction, specifically the carbon that could be captured on land if it was not needed for beef production. The carbon footprint of beef (from a beef herd) more than doubles to 227 kg CO2eq / kg beef.

Total GHGs from beef production

In the previous post, the total footprint of beef was comparable to the steel and cement industries, contributing 6% of global GHGs. Now, if we include this correction for land use, it comes to around 12.5% of global GHGs.

This revised data has not been so widely disseminated as the original paper. This is a missed opportunity as it clearly shows a path forward for climate change mitigation. Of all products made on the planet, including the massive amounts of cement and steel used for construction, beef is categorically responsible for the most GHGs, by a very wide margin.

And that applies whether you look at the total contribution to global GHGs (12.5%) or the footprint per kg.

What’s the carbon footprint of the beef in a typical diet?

Let’s complete this analysis by looking at how beef consumption contributes to our individual carbon footprints. Imagine a person who eats 1 lb. of beef (454 grams) per week that comes from a beef herd (a cut of beef, Angus burger, etc.). That amounts to 23.6 kg per year and using the revised carbon footprint of 227 kg CO2eq / kg beef, this corresponds to annual GHG emissions of 5.4 tonnes CO2eq.

At the beginning of 2024, I considered 7 tonnes CO2eq to be a reasonable immediate carbon footprint target for anyone living in the Global North. This is an achievable resolution for many, but clearly well out of reach for anyone consuming as much as 1 lb. of beef per week.

I’d like to hear your thoughts on this – please comment below.

Notes on my calculations

I believe that these estimates for the carbon footprints of beef (both the “per kg” number and the global total) are underestimates for a couple of reasons. One, I’m not including the very low intensity cattle grazing that takes place in Africa and parts of Asia (Kazakhstan, Mongolia). To include this data would push the land and carbon footprints of beef even higher. Two, I didn’t attempt to factor in the fact that some land (e.g., rainforest cleared for cattle grazing or growing feed) will have a higher capacity to sequester CO2 if allowed to regenerate.

[More detail: I used the total land footprint for animal products from Poore & Nemecek’s main dataset, which comes to 2.07 million hectares. 38% of that land is used for beef herds and 3.9% for dairy herds. I excluded the 1.36 million hectares of low-intensity grazing land (FAOSTAT) that was added by Poore & Nemecek to their total. If I had included this data, the percentage of land used for beef production would have been considerably higher.]

Total beef consumption (beef and dairy herds) averages well over 1 lb. per week (23.6 kg per year) in many countries. US residents consume a little over 1.5 lbs. of beef per week, on average.

On a global scale, if everyone on earth ate 1 lb. of beef from a beef herd per week, the GHG total would be 43 billion tonnes CO2eq – that’s almost as much as the entirety of current global GHGs. Most of our rainforests would also have to be removed to make room for beef.

Discover more from The Green Stars Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

To believe that people are going to become vegetarians is unrealistic. And a vegetarian diet is not healthy for everyone. Everybody’s chemical makeup is different. Most people have already expressed a revulsion to eating insects, etc. The methane from cattle can be converted into biofuel, as some companies are already doing.

LikeLike

Hi Dawn,

Thanks for your comment.

I already acknowledged that “The whole world is unlikely to go vegan overnight, so let’s zone in on a realistic target: the animal product with by far the biggest carbon footprint.”

Therefore, this post is specifically about the carbon (and land) footprint of beef and examines what would happen if we cut this one product from our diets. Omnivores can eat eggs, fish, chicken and pork instead of beef – this would be hugely beneficial.

This new revised carbon footprint of beef is vital information for anyone why wants to mitigate climate change.

Capture of methane from cattle (e.g., in anaerobic digesters) is already factored into the original carbon footprint (100 kg CO2eq / kg beef). The carbon footprint increase reported here (from 100 to 227 kg CO2eq / kg beef) is purely due to land use – it has nothing to do with methane production.

LikeLike

Plus it leads to colon cancer so why do people love it so much, James?!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, I guess people love lots of things that are bad for their health 😉

Substitutes have health benefits and huge environmental benefits – I think the cost just needs to come down a bit.

It’s why I usually buy mine at the Grocery Outlet – it’s a good way to try out beef-alternatives on a budget.

Cheers!

J

LikeLiked by 1 person