This is a follow up to my last post on Bill Gates’s 2021 book, How to Avert a Climate Disaster, covering what I believe is the biggest opportunity missed in the book: a clear comparison of the carbon footprints of steel, cement, and beef.

My biggest issue with Gates’s book on climate is that it sometimes gives the impression that the mitigation of climate change is much more reliant on researchers, entrepreneurs, and policymakers than on consumers. But it’s very much a job for both sides – producers and consumers. The success of entrepreneurial products like plant-based meat is entirely dependent on consumer adoption.

So why should we specifically look at the carbon footprints of steel, cement and beef in this blog post?

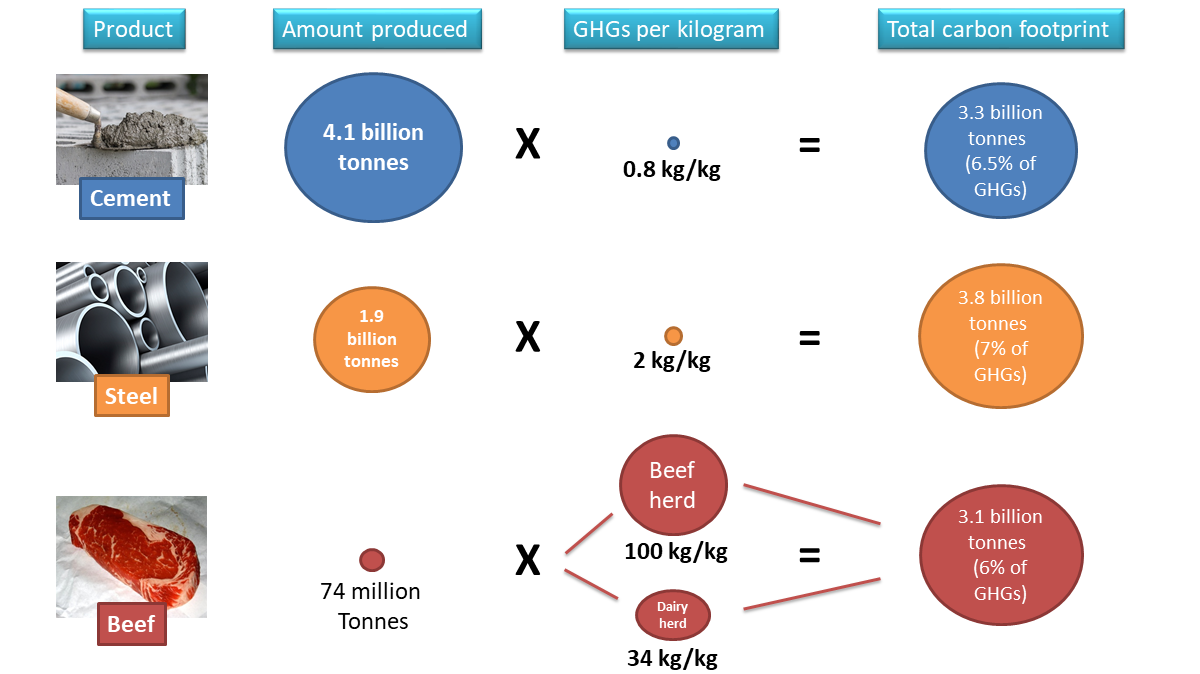

Well, the first two – steel and cement – are each responsible for 5-7% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Together, they account for almost half the GHGs from the entire manufacturing sector (plastics come in third). So they are a big deal and do somewhat rely on technological solutions, but many are actually already in the market – I’ll cover solutions briefly at the end. And then there’s beef.

Globally, we produce (consume) way less beef compared to steel and cement and yet the beef industry’s total carbon footprint may be the largest of the three. The fact that the carbon footprint of global beef production is as high as (or higher than) those of steel or cement is not really an obvious fact. Different sources – and AI engines – give quite different answers.* Bill Gates discusses details like methane from cows but doesn’t mention the total carbon footprint of the beef industry in his book.

*Don’t get me started on the accuracy of information from AI (e.g., on Google search) – a topic for another post.

Cement and steel have high total carbon footprints, because of the massive amounts produced globally, but their footprints per kg are not especially high. The carbon footprint of beef, per kg, is 50-100 times higher than steel and cement – that’s critical data for anyone concerned about climate change.

Let’s look at the data in graphic form, below. The numbers for beef come from a respected paper (Poore and Nemecek, 2018) that I covered in a post on the carbon footprint of various foods. Thanks to Dr. Joseph Poore for kindly providing additional information for this blog post.

The total carbon footprint of beef shown above is actually a large understatement. In erratum for the Poore and Nemecek paper, the authors pointed out that the benefit of reducing meat consumption is actually far greater than they had originally thought.

Basically the land that would be freed up if we avoided animal products “could remove around 8.1 billion metric tons of CO2 from the atmosphere each year over 100 years as natural vegetation re-establishes and soil carbon re-accumulates.” Beef would account for a lot of that as it has a massive land footprint.

So that’s really significant and I’ll revisit it in a future post. Going back to the key point in the image above: A high carbon footprint per kg of product makes a huge difference. Let’s call this the carbon footprint multiplier.

Carbon footprint multipliers

Let’s examine the carbon footprint of beef that you’d buy as a consumer. Most beef, such as a cut of steak or an Angus beef burger, comes from a herd of beef cattle (as opposed to a dairy herd) and has a carbon footprint multiplier of 100. In other words, each kg of beef that you eat has a carbon footprint of 100 kg of CO2 equivalents (CO2eq).

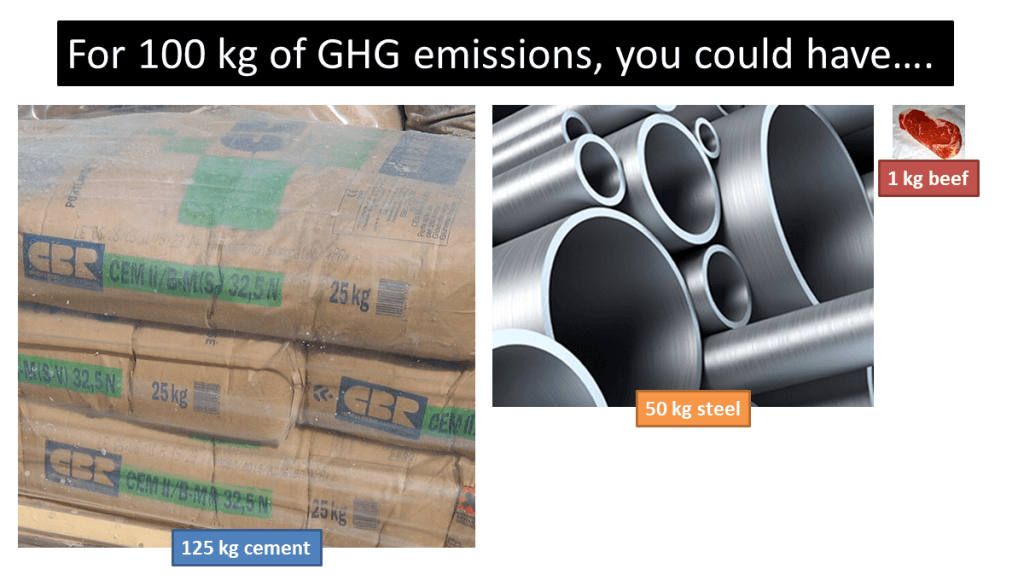

So the carbon footprint multiplier for beef is 100 is while for cement and steel it’s only around 0.8 and 2, respectively. In fact, most things have a multiplier in the low single digits and very few* items come even close to beef.

*Hydrofluorocarbon refrigerants have very high carbon footprints per kilogram, which is why the development of green refrigerants has been very helpful. But you’re not likely to go through kilograms of refrigerant, unless you’re in the habit of trashing air conditioners or freezers.

Many of the products with the highest carbon footprint multipliers are foods (predominantly animal products) which is obviously an issue as we consume a lot of food. Beef tops the list with a multiplier of 100 and the only products that come close are lamb (40), beef from a dairy herd (34), farmed crustaceans (27) and cheese (25). NO – not CHEESE! I hear you scream.

I actually would have thought that we consume more cheese than beef, worldwide, but no. Around 23 million tonnes of cheese is produced globally and then factoring in the carbon footprint multiplier (25) and food waste, this amounts to a total carbon footprint of less than 0.5 billion tonnes CO2eq (around 0.8% of GHGs). That’s still a lot but not nearly as high as beef’s footprint.

So when we consider both the multiplier, the amount consumed globally, and land use, beef takes the trophy for the product with the largest total carbon footprint. If you’re an omnivore, take a look at the environmental footprints of food and consider animal products with lower footprints such as fish, chicken, pork, or eggs.

Also consider how long a product lasts. Stainless steel for consumer products may have a higher carbon footprint multiplier (around 6) than steel for construction, but it’s still not a big deal when you consider that a stainless steel cooking pan or coffee mug lasts for years. Beef is gone in one meal.

It’s always good to put things in perspective. If you needed to buy 100 kg of cement for a construction project, consider that the carbon footprint multiplier is 0.8 so the carbon footprint for that cement is 80 kg CO2eq – less than that of 1 kg beef.

Since this is a continuation of last post on Bill Gates’s 2021 book, How to Avert a Climate Disaster, let’s take a look at what Bill has to say about beef.

Bill Gates on meat

In How to Avert a Climate Disaster, Bill Gates does discuss the importance of cutting down on beef. But he also says that “a hard-core vegan might propose another solution” – to stop eating meat. I’m not sure why he hyphenates hardcore but perhaps it’s to emphasize how square he is while dissing the vegan proposal.

He continues, “I can see the appeal of this argument but I don’t think it’s realistic.” His reasons include that meat plays an important role in human culture. Here’s a quote:

In France, the gastronomic meal – including starter, meat or fish, cheese, and dessert – is officially listed as part of the country’s Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. According to the listing on the UNESCO website, “The gastronomic meal emphasizes togetherness, the pleasure of taste, and the balance between human beings and the products of nature.”

FFS, Gates! Is that all you can come up with? The UNESCO quote doesn’t even mention meat, and even still, you can go for chicken instead of beef reducing the carbon footprint 10-fold (coq au vin instead of boeuf bourguignon).

He does go on to talk about meat substitutes being very good now and how he has invested in companies in that space. But it’s his mixed messaging that’s most disappointing. The reader’s impression will be that, yes, it’s alright to eat lots of beef because it’s part of my culture. And that those vegans and vegetarians are just hardcore extremists.

He discusses steel and concrete at length but fails to emphasize that cutting beef is the easiest and most impactful change we can make as consumers.

Climate solutions for steel and cement

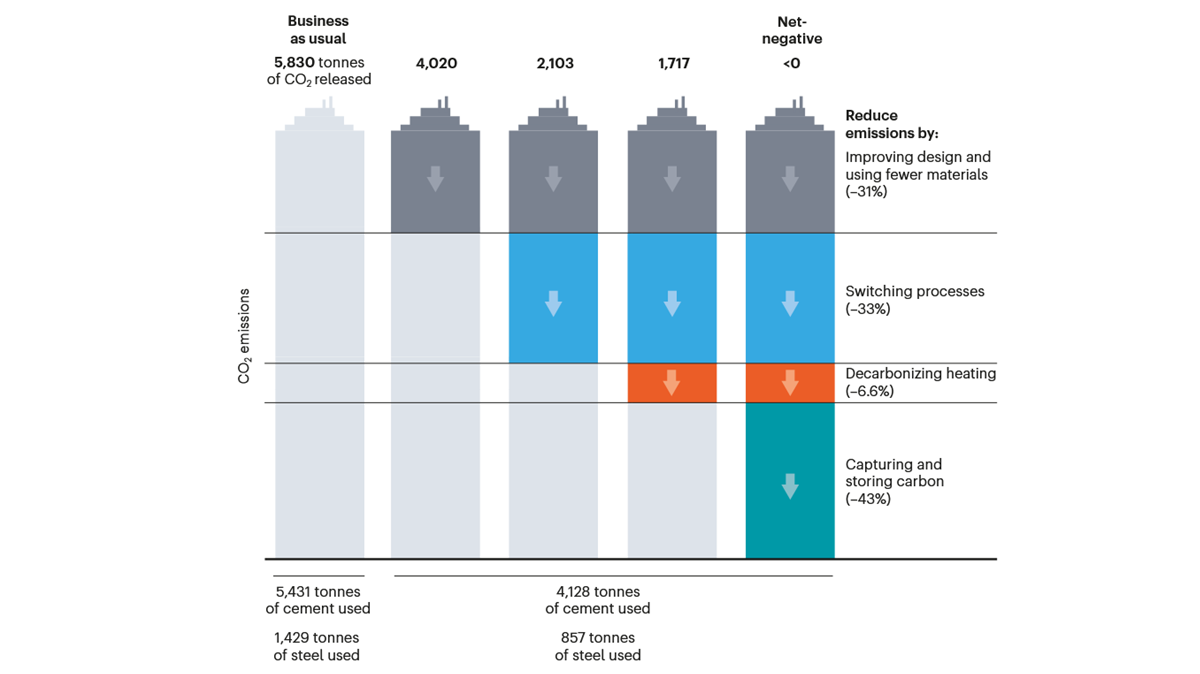

As a quick wrap-up I want to briefly touch on reducing the carbon footprints of steel and cement.

Of course, most cement and steel is used in buildings like skyscrapers, and a lot of that construction is going on in countries currently undergoing development. This is why books that focus on these topics can make climate change feel out of our hands at times. However there are clear paths to reducing the carbon footprint of construction materials.

One of the most useful science papers on this topic is Going net zero for cement and steel (2022). It’s a practical paper that mentions cement and steel producers that are already employing (or at least developing) some of the solutions.

One promising example is limestone calcined clay cement (LC3). With similar properties to ordinary Portland cement, it’s already close to being commercialized and would be easy to switch to. Some companies already include LC3 technology in their net-zero strategies, among them [Swiss-based Holcim] and Germany-based Heidelberg Materials.

Here’s a chart from that paper, describing various ways in which GHG emissions from cement and steel can be reduced (and the bars are in the shape of skyscrapers!).

Optimizing carbon capture in concrete is an active area of research. Leaders such as CarbonCure in Dartmouth, Canada, are already injecting CO2 in concrete at a large scale: it reports that it has delivered nearly 2 million truckloads of CarbonCure concrete, saving 132,000 tonnes of CO2.

So, solutions are in progress for reducing the carbon footprint of steel and concrete production, using less of them in construction projects, and replacing them with more sustainable materials in some situations.

That leaves us, as individual consumers to focus on minimizing consumption of products with very large carbon footprint multipliers, especially beef.

Discover more from The Green Stars Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

👌👌

LikeLiked by 1 person