We’re all used to hearing about plastic pollution – plastic in the oceans, microplastics in our bodies, etc. But we don’t talk a lot about the carbon footprint of plastic production. This is going to be a fairly brief post (really!) relaying recent data on the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of the plastics industry – data that deserves a lot more attention.

I’m wrapping up (and hopefully publishing!) a book on ethical consumption, updating a few chapters as new information becomes available. In my original draft of Chapter 5: Waste, I discussed how plastic, and specifically plastic packaging, has grown to dominate our waste stream:

On a global scale, around 400 million tonnes of plastic was produced in 2020 – more than the weight of the entire human population. Of the plastic waste generated globally to date, only around 10% has been recycled; 14% has been incinerated, and 76% has been disposed of in landfills or released into the environment.

(More than the weight of all of us humans – every year!!)

So, plastic pollution aside, what’s the carbon footprint of producing so much plastic?

GHG emissions from the plastics industry

A report titled Climate Impact of Primary Plastic Production was published in 2024 by scientists from Lawrence Berkeley National Lab (LBNL). Its main finding:

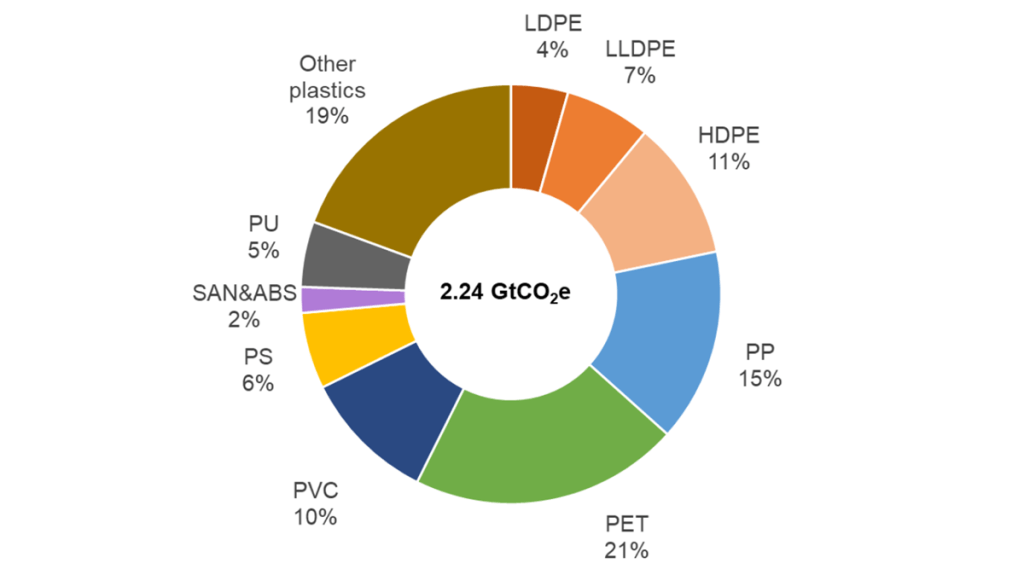

The annual carbon footprint of synthesizing plastic is now estimated to be around 2.2 billion tonnes of CO2-equivalents (CO2e) – that’s almost 4% of global GHG emissions.

This is more than double the number I had previously used for my book chapter (from this reference). Here’s the rest of my revised Chapter 5 paragraph, summarizing that data from LNBL:

Of the major industrial materials, the production of plastics is experiencing the fastest growth rates (close to 4% per year) posing a very significant threat to climate change. If this growth continues as projected, the plastics industry will be responsible for annual GHG emissions of 5-7 billion tonnes of CO2 by 2050. In that scenario, cumulative emissions from 2020 to 2050 are likely to reach 100 billion tonnes of CO2, which represents one fifth of the GHG emissions budget for limiting global warming to 1.5°C by 2050. Unlike other industries, such as transportation, petrochemical-based plastics have little scope for decarbonization.

That paragraph is a bit heavy on information but I think it’s worth taking a moment to consider it. Here’s another way of looking at it: Annual GHG emissions were estimated to be 59 billion tons CO2e in 2019 (IPCC AR6 report) and of course this need to be reduced* drastically by 2050. If the plastics industry ends up producing 5-7 billion tonnes of CO2 annually by 2050 it could rank as the largest or second largest driver of climate change by then. (Assuming we make progress on cutting meat consumption and increasing renewable energy.)

(*We need to reduce global GHGs to less than 20 billion tons CO2e by 2050 if want to keep global warming below 2°C.)

Funding for climate research wanes

As mentioned, this report on the carbon footprint of the plastics industry was published by scientists from LBNL, a US national lab, in 2024. The work was sponsored by the United States Government, funded through the Department of Energy. Would it be published in 2025? What do you think?

LBNL has recently experienced a round of cuts and layoffs due to cuts in government funding – particularly climate change research. As I’m writing this post a former colleague posted online about being laid off.

Personal action on plastic and climate change must rise!

Government support of climate initiatives and environmental regulation is clearly in peril. In the US, it’s openly being dismantled but it’s happening elsewhere too. It’s particularly obvious in the behavior of corporations and organizations that no longer feel that they need to behave themselves. Just this week, the highly successful Soy Moratorium was suspended, posing a serious threat to the Amazon rainforest in order to produce more animal feed.

Similar shenanigans are afoot in the petrochemicals industry, which provides the raw materials for plastic production. For example, British oil company BP, which was once re-marketed as Beyond Petroleum to indicate a move away from fossil fuels, ditched its climate targets in February.

All of this makes our actions as consumers more important than ever – that really can’t be overstated.

When it comes to plastic, my approach is pretty simple: set yourself a budget for the amount of landfill waste you generate each month. I’ll share an excerpt from Chapter 5: Waste, next month, that provides more detail on this idea.

Most of us will continue to buy a few items that are sold in plastic packaging – this is hard to avoid completely for the average, busy person. It can be especially challenging when combined with other steps towards an ethical lifestyle. For example, if you’re moving towards plant-based diet and at the same time trying to go plastic-free, this is a lot to handle. At the same time, we can do a bit of both, for example by shopping in bulk sections or checking out a zero-waste store.

No matter what your path, the most practical, balanced approach is simply to set a quota on the amount of landfill waste that you are comfortable producing (a small bag per month or per week) and then stick to that.

In the upcoming series of posts on the stuff we use in our daily lives, I’ll be looking at options that use little or no plastic.

If you want to read more about plastics, I highly recommend reading the UN Environmental Program’s 2021 report, Drowning in Plastics. It’s a wealth of information, clearly explained with nice graphics.

Discover more from The Green Stars Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Plastic is so ubiquitous that it’s a challenge to entirely avoid usage. Thanks for the link to the UNEP’s 2021 report.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Agreed, Rosaliene. That’s why I think setting a waste budget for ourselves is the best approach.

You’re welcome!

J

LikeLiked by 1 person

Why, in this technological world, haven’t “they” been able to develop more ethical packaging (or is there any motivation to even so so)?

Even though I have been known to complain to companies about their packaging, many times I am forced to purchase overly plasticized products. There are no other options. Frustrating!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Alanna!

Thanks for your comment!

A full response to the first question requires a blog post of its own so I will put that on the to-do list! I’ve worked in the bioeconomy area as a scientist and there are lots of people working on solutions to the plastic problem. Some are working on new polymers that can be truly recycled without degrading over time. Others are working on better conversion of plants into plastic-like polymers. An example of the latter that you’re probably familiar with is the compostable polymer PLA (polylactic acid). Lactic acid is produced by fermentation, starting from plant sugars (made from CO2 by photosynthesis) and then polymerized to make PLA. Some further improvements would be good here but a few companies are already making products with much lower carbon footprints compared to conventional plastic.

Then there are companies that have moved away from plastic packaging by finding paper-based products that will work. For example Beyond Meat sausages and the new packaging for Earthbound Farm salad greens, which I covered recently. It’s good to support these developments because these innovations in packaging won’t take off if customer demand is not high enough. (This has happened in the past – for example compostable packaging from Sun Chips. Unfortunately this was probably just a badly designed product and as a result Sun Chips’ parent company PepsiCo messed up the reputation for compostable packaging for quite a while.)

Please let me know the specific products that you find are always over plasticized and I will look out for good options 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks for your thorough answer. It’s hardening that there is some movement in this area. I look forward to your blog post in the future!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Changing packaging to more ethical options would be a major step. I wonder if packaging science students of today and recent years are being taught those options / if we could highlight those more. It mainly comes down to money, as you already know (choir 🙂 ). Can they do it for the same efficient cost as plastic? Until we can do that, it’s still the uphill battle. (Impressed that you are always fighting this good fight. Keep up the excellent work!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Andrea!

Thanks for chiming in 🙂

Doing it for the same cost as plastic is definitely a challenge.

But the good news is that the cost of packaging is usually a very small fraction of the cost of the product inside that packaging. Even still, the only incentive (other than altruism) for companies to use better packaging (even if only slightly more expensive) is if consumers appreciate it (and sales are slightly higher).

Thank you!

J

LikeLike

When I was growing up, everything came in glass containers, we had paper straws, and cloth diapers. Glass, paper, and cans were recyclable. On the positive side, some companies like Chevron are developing technology to break plastic down and even turn it into fuel. It’s important to highlight and give credit to the companies doing that since plastic is not biodegradable.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comment, Dawn!

For sure, there are several companies and even more academic labs working on solutions.

Chevron’s plan had some issues but maybe with some modifications it could be done safely.

Other companies, such as Carbios are working on technology to break plastic down to monomers that can be rebuilt into fresh plastic. The economics of that are challenging but it’s already happening on a small scale.

And yes, for sure we should support companies that are replacing plastic packaging with plant-based packaging that’s recyclable and/or compostable. Cheers!

LikeLike

Great post! I am so concerned about our environmental problems. My husband is a well known naturalist in the New River Valley and also concerned about what we are doing to harm the home our planet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

Hope it inspires you to set a budget on your landfill / plastic waste

LikeLike

Without federal legislation, the problem will continue to fester, killing marine life, and us, too, since we all have microplastics in our bodies. I honestly don’t know what it’s going to take for legislators to wake up, James, but it’s well past the 11th hour.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Pam!

Sadly, fed legislation ain’t happening anytime soon in the US, as you know, but state legislation might. Either way, it largely depends on our own decisions to cut back on unnecessary plastic purchases and support alternatives.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And that’s such a heavy lift for some, especially without a lot of options. Manufacturers need to start making more sustainable products for us to choose from.

LikeLike

😱

LikeLike

We’ve been trying to find ways to reduce our use of plastic but man it’s not easy. One thing is we stopped using the Keurig and went back to regular drip and/or French press coffee, and lately I’ve been trying to buy things like yogurt and olives that come in glass containers, but it’s not even a drop in the bucket. Still, do what you can, right?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for chiming in, James 🙂

Yes indeed – do what you can!

Good luck on your journey,

J

LikeLike