In this post I’m going to take a look at the topic of preserving the world’s remaining forests. As usual, I’ll do this by focusing on a seminal science paper (or two) that has proven to be a trusted authority on the topic. Thank you for reading these posts, by the way – I know they require a little effort, but we live in a time when getting the story straight is important. This is the third in a series examining the impact of our diets on the largest environmental threats to the planet.

I’ll mainly be discussing a 2016 paper: Exploring the biophysical option space for feeding the world without deforestation. The title brings up two points that highlight why the paper is significant:

1. Food production systems determine humanity’s survival on two levels: food security and environmental stability. Can we feed ourselves without ruining the planet?

2. Of all our environmental impacts, deforestation is arguably the most critical. That requires a little explanation, so let’s get into that, briefly.

Forests are of primary importance to the planet

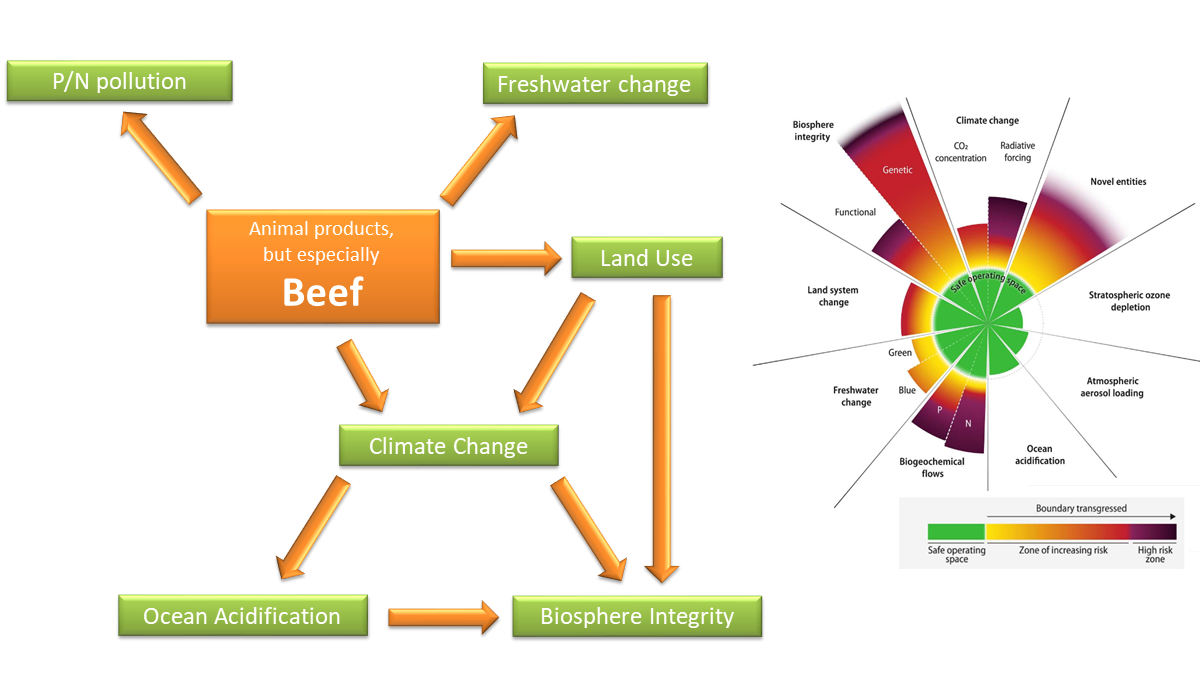

The authors of this paper (scientists at the Institute of Social Ecology in Vienna, Austria) acknowledge that there are many environmental consequences of food production, including climate change, eutrophication (nitrogen and phosphate pollution), and biodiversity losses. These are three of the nine major environmental threats to life on Earth, known as planetary boundaries, discussed in my last post. But, having to choose one for the study they selected deforestation (the planetary boundary is called land system change or land use change) as the most important.

One of the reasons why avoiding further deforestation is so critical is that it’s a driver of several other planetary boundaries into the danger zone. Here’s a quick review of the ways deforestation impacts other planetary boundaries:

- Climate change: Land use change (mainly deforestation) is responsible for around 11% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (last IPCC report).

- Biodiversity losses: Deforestation has a huge direct impact on diversity as that’s where most of the planet’s unique species live. It also has the indirect impact on biodiversity by worsening climate change.

- Ocean acidification: CO2 emissions from deforestation (and other sources) drive acidification of our oceans.

- Freshwater availability: Deforestation impacts this indirectly by driving climate change, but also directly by causing soil to dry out.

- Air pollution (atmospheric aerosol loading) is significantly worsened by the burning of forests and peatland.

Forests also play a major role in cleaning the air and buffering the climate against extremes. Bottom line: we really need them! As the authors of this paper put it:

Protecting the remaining forested ecosystems is a central desideratum in this context. Forests store more carbon than any other land-cover type per unit area and host a considerable fraction of the global biodiversity.

Our diets determine the rate of deforestation

The authors of the paper explored various scenarios for feeding ourselves. The options included whether we: Grow crops organically or intensively (the latter bumps yields around 25-30%, but at a price); Convert some of the best-quality grazing land into cropland; Raise animals on pasture or on grain; Follow a vegan, vegetarian, global average, or meat-rich diet; Eat animal products from ruminants or monogastric animals. I’ll get back to that last one 😉

These are all good factors to consider as they all impact land use (deforestation) and are almost all consumer-facing decisions. Together, these factors determine the likelihood of being able to provide food for ourselves without having to remove forest to provide more land for agriculture.

So, the central question of the paper is: Which scenarios are feasible if we want to feed a human population of around 10 billion people in 2050 without further deforestation?

It turns out that the most important variable in all of these scenarios is not crop yield or grazing land conversion but simply our diet – specifically how much meat we consume. This shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone who has read the last two posts on the environmental footprints of meat and the planetary boundaries. But there are some nuances of interest here that make the paper worth examining. The scientists have evaluated the feasibility of several scenarios that people often wonder about, such as pasture-raised meat and organic produce.

Before getting into those nuances, I’m going to show an edited version of the main figure from the paper, showing 200 different scenarios. Each square represents a different scenario and is shaded green when feasible and brown when not feasible without further deforestation. See the paper for more detail and a figure showing all 520 scenarios. This figure captures the most important extremes. Don’t worry if it’s not very understandable yet – I’ll explain in more detail later.

I think the best way to describe the findings is to go through the variables that the authors evaluated and look at how they impact our forests.

The American diet is not compatible with organic/pasture-raised food

The Rich diet that the scientists examined is based on the average American diet – rich in animal products. As you can see from the block of brown squares (lower left) in the figure above, there is no scenario where we can all eat this rich diet and also grow crops organically without destroying forest to make room. The combination of the large land footprints of meat and the lower yields of organic farming means that forests have to be cut to make room for more meat.

Even if we grow crops by intensive agriculture and improve crop yields by 10% (the high-yields/rich-diet scenarios occupying the top left block of squares) deforestation is still likely. Only a few scenarios work in that instance, and they are restricted to the following conditions:

First, global consumption of animal products at American levels would require that the animals are intensively raised in feedlots. There is simply not enough grazing land to support pasture-raised animals. Additionally, in order to provide feed for these these animals, most/all suitable grazing land must be converted to cropland. And, as mentioned, crop yields have to be raised 10% above the current average, meaning that we would need to rely even more on industrial agriculture.

There are a few scenarios where we can combine modest levels of meat consumption with organic agriculture and even some pasture-raised animals. They still require that a good amount of grazing land is converted to cropland but they can, at least, avoid deforestation. These scenarios entail that we follow something close to the global average diet (The BAU diet in the image above) with a lower intake of animal products than the rich diet.

Meat consumption in the US is three times higher than the global average (and beef consumption is four times higher). To match the global average, meat consumption in the US should drop from current levels of 5.5 lbs. (2.5 kg) per person, weekly, to 1.8 lbs. (0.8 kg) of meat per week. In addition, if we want the option for animals to be pasture-raised, then a good amount of our animal products should come from monogastric animals (chickens and pigs).

Why are ruminants more problematic than monogastric animals?

Why are the scenarios for consumption of animal products more likely to work when they rely less on ruminants? In the post on the environmental footprints of protein-rich foods, we saw that beef and lamb have massive land footprints and also massive carbon footprints. Cheese, another ruminant product, didn’t do so well there either – much worse than eggs. Curiously, these large carbon and land footprints come down to the fact that cows and sheep are ruminants.

Ruminants have special digestive systems (four stomach compartments, including a rumen) that allow them to digest grass and other fibrous plants. The other animals that we commonly eat for food – chickens and pigs – are known as monogastric animals, meaning that (like us) they have one stomach. There are two main reasons why food products from ruminants have larger land and carbon footprints than monogastric animals:

- The conversion rate of feed into meat is much lower in ruminants than in monogastric animals.

- When ruminants digest fiber, some of the carbon is emitted as methane, a potent GHG.

Reducing our consumption of ruminant products (beef, especially) is one of the best ways to preserve our forests and also mitigate other planetary boundaries such as climate change. When we reduce our overall meat consumption, the benefits extend to avoiding the need for cropland expansion or higher crop yields.

The downsides of cropland expansion

Total cropland on Earth could be expanded by 70%, if needed, by taking over all of the grazing land that’s flat and rich enough for agriculture (that’s roughly a fifth of total grazing land). An ethical downside, discussed above, is that this conversion is part and parcel of the intensification of animal farming (to meet a higher demand for meat). A major environmental impact is that more cropland means more agricultural inputs (fertilizer, water, and pesticides). Another downside is that agricultural land is not a hospitable place for wildlife (small mammals, migrating birds, pollinators, etc.) compared to wild or grazing land.

The expansion of cropland becomes less problematic if the method of farming is more sustainable – organic, for example. Agricultural inputs are lower and land is more wildlife-friendly. But crop yields are typically lower on organic farms, so that also needs to be taken into account.

The tradeoff of higher crop yields

Getting good yields from agricultural land is important if we want to avoid deforestation. But there’s a tradeoff here since the highest yields often come with a high price for the environment. There’s also a pretty high risk that land becomes degraded if agricultural practices are too intensive. Land becomes less resilient to weather extremes when higher yields are gained at the expense of soil quality, water retention, and local biodiversity.

Besides this, further increases in crop yields are going to be hard to achieve, especially when most evidence shows that yields will actually suffer due to climate change. The cost of squeezing out another 10% increase in crop yields has to be weighed against any benefits and it obviously depends on how that increase in yield is achieved.

To be frank, the scenario of continuing to eat meat-rich diets by doubling down on intensive, industrial agriculture is a very dangerous bargain. Even just from the perspective of food security and feeding the population in 2050 (which is not that long away!), it’s not scientifically sound. Besides the likelihood of the higher yields of industrial agriculture being unsustainable, the environmental footprint of this way of life poses an existential threat to the planet. – My upcoming book (seeking a publisher!)

Vegan and vegetarian diets

If everyone followed a vegetarian diet, almost all of the scenarios examined (113 out of 120) are feasible. Even when combined with organic farming, pasture-raised animals and zero cropland expansion, most scenarios are feasible with a vegetarian diet. If everyone was to follow a vegan diet then every scenario is feasible and we would also have a lot of land left over. In fact, the scenarios described in this paper on feeding the world without deforestation may have even underestimated the benefits of vegetarian and vegan diets. Two year after this paper, Poore and Nemecek released their seminal paper on food’s environmental footprints. They expressed it the land preservation benefit of a vegan diet as follows:

Moving from current diets to a diet that excludes animal products has transformative potential, reducing food’s land use by 3.1 billion hectares (a 76% reduction). In addition to the reduction in food’s annual GHG emissions, the land no longer required for food production could remove around 8.1 billion metric tons of CO2 from the atmosphere each year. [8.1 billion metric tons of CO2 is around 14% of global GHG emissions, as reported by the IPCC.]

So the amount of land we use for food production would be cut to around one quarter of current needs in a vegan diet scenario. All of the land that is freed up can be rewilded, reforested, or in some other way returned to nature.

Discover more from The Green Stars Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

And yet, here we are, voting against our self-interest time after time after time…

LikeLike