Anyone who eats animal products but wants to reduce their environmental footprints should consider fish over meat. Like many, I continued to eat a little fish while transitioning to vegetarianism and found it to be a helpful way to kick the meat habit. This also works long-term for many: around 3% of the world’s population follows a pescetarian diet which includes fish but no meat. I’ve now largely cut dairy from my diet, after studying its environmental and ethical impacts, and can see some valid arguments for choosing seafood over cheese.

Of course it’s even better to just go plant-based, as much as possible, but I want to be realistic and discuss some of the best non-plant foods – and also to cater for readers who serve furry overlords!

So are seafood certifications helpful in making responsible choices? I would say yes right now, but I haven’t finished my research yet. Let’s see if I still think yes by the end of this post! But the specific kind of seafood that you choose is just as important, if not more so, than whether it’s certified.

In my recent post on the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), I used the example that choosing a wooden chopping board is, a priori, a better choice than a plastic board – that’s the first level of your decision-making process. Then the second level is to choose a board made from wood that’s responsibly managed.

Same thing here with seafood: First choose a type of seafood based on broad environmental factors and then look for a certification that the fish stock is responsibly managed.

Step 1: Choose the right kind of seafood

Before getting to seafood is certified sustainable or not, it’s worth considering that some types are inherently more environmentally friendly. I’ve covered that topic broadly in a previous post on sustainable seafood and I also plant to cover a few specific kinds of seafood in an upcoming series of posts on the ethics of our most common purchases.

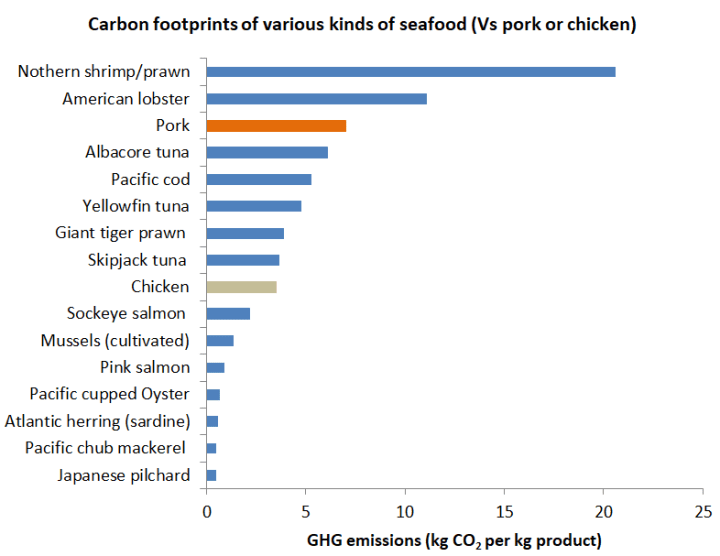

For example, three categories of seafood score have the lowest greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions:

- Small pelagic fish (sardines, herring, mackerel, anchovies, etc.)

- Farmed bivalves (mussels, oysters, clams, cockles, and scallops)

- Wild salmonids (salmon, trout, char, and other fish in the salmonid family)

As you can see from the chart below, wild crustaceans (shrimp, prawns, and lobster) generally have the highest carbon footprints. I’ll refer you to that post on sustainable seafood for some detail on issues such as avoiding bycatch (small pelagic fish and fish caught by pole-and-line are good here) and why shrimp can be an environmental disaster. You can also consult the Seafood Watch guide to get an idea of some of the best choices.

Coming up, I will examine whether third-party certifications are useful for identifying responsibly-caught seafood. But before that, there’s one more factor that we should consider.

Step 2: Choose locally-caught fish, when possible

It’s generally much better to buy fish that has been caught in your own country. There are a few reasons for this. Transportation is a factor here for frozen or chilled seafood because refrigerated transportation has a higher carbon cost than regular transport. But that’s not the main reason – I think its fine to buy products that have been transported a long distance if they support people and the environment where they originate (e.g., Beyond Good chocolate that’s made in Madagascar).

For seafood imported from the Global South, however, much of what’s sold in conventional supermarkets does not support people or the environment. It risks depleting fish stocks in nations where seafood is a key food source for locals, while also exploiting workers. (There are some notable exceptions, however, and a hope that certifications can protect against these downsides – see Step 3, below).

The state of global fish stocks

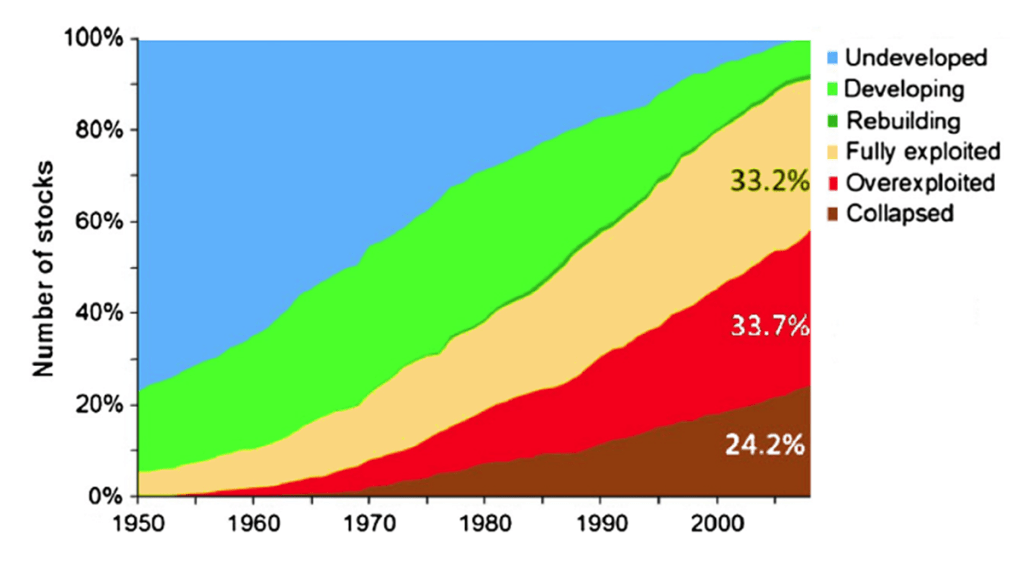

In a key 2013 paper on the state of global fisheries, the authors pointed out that fisheries in the developed world are in better shape than those in the Global South:

While there is indeed some evidence of small improvements to fisheries management in the developed world, over 80% of the world’s fish are caught elsewhere and so this does not support a message of confidence. – Fisheries: Hope or despair? (2013)

An update on this paper, published 2024, reported that:

While there is a growing recognition of the need for sustainable fisheries management and ocean protection, the overall status of fisheries has not improved.

A critical step toward sustainability is to reduce the overall fishing effort and shift to lower-impact fishing methods.

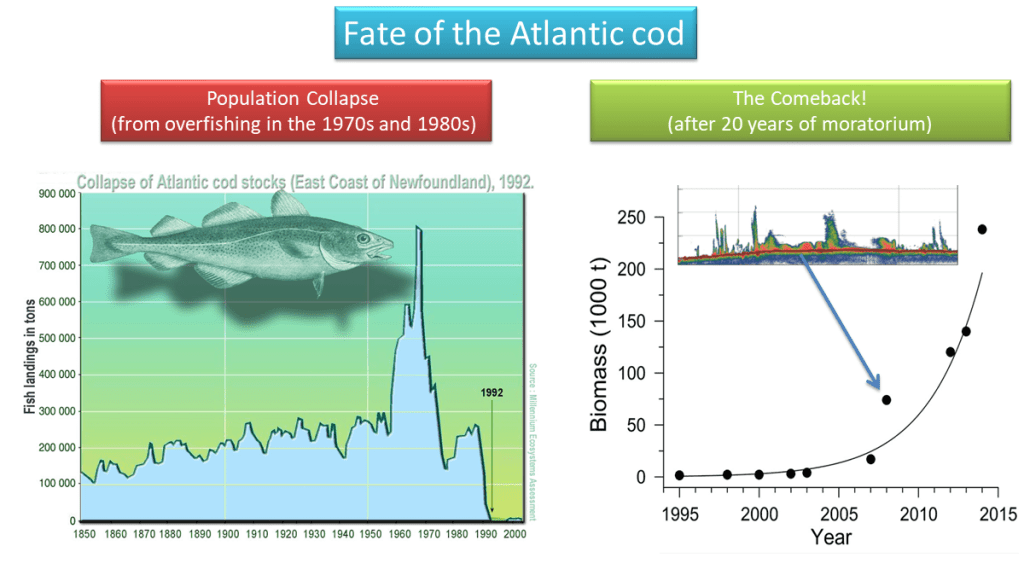

But just to show a bright spot – there are cases where fish populations have rebounded, showing that it is possible. The very thin dark green line in the chart above shows the small proportion of cases where rebuilding of stocks is taking place. The Northwest Atlantic cod fishery is one such example, shown in the two charts below.

But most fisheries in the Global South are unlikely to experience this kind of recovery while competition among multinationals and major supermarkets results in the erosion of price, worker welfare and fishery health.

Up to a third of imported fish is illegal

It was estimated that Illegal and unreported catches represented 20–32% by weight of wild-caught seafood imported to the USA in 2011. The research highlights many cases where seafood imported from China or Thailand is often only processed in these countries. Illegal catches might come from Russian boats that are exceeding quotas or from deals made at sea to avoid citation for overfishing. The seafood is frozen, shipped to China/Thailand/Indonesia, etc., thawed, processed, and then refrozen or canned for export. That number may be lower today but it’s certainly still going on.

Whether we buy local or imported seafood, does a third-party certification help mitigate overfishing?

Step 3: Look for third-party certifications

The seafood certifications that you’re most likely to come across include the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) and Friend of the Sea (FOS). However, I first want to mention that you can also find fair trade certified seafood.

Fair trade seafood

Fair Trade USA certifies various kinds of seafood, including shrimp, tuna and tilapia. One example that I’ve come across is canned skipjack tuna from The Mind Fish Co., which I bought for my cat a few times and she enjoyed. Besides being fair trade certified, the tuna is also pole-and-line caught in the Maldives, which virtually eliminates bycatch issues. In fact the Maldives has banned the less-discriminating practice of long-line fishing in order to protect ocean biodiversity, including threatened shark species.

Fair trade certification helps secure livelihoods and communities against the ravages of price competition, such as that reported for the shrimp industry. Research from Sustainability Incubator, a Hawaii-based nonprofit that advocates for better conditions in the seafood industry, found that conditions have deteriorated in response to shrimp market prices reaching a record low in 2024:

The typical working conditions in India, Indonesia, and Vietnam include 9 to 14-hour workdays for 20-60% lower earnings than before the pandemic, no payment for overtime, and lost bonuses and benefits.

With worker exploitation rampant in the industry, I think fair trade certified seafood is a good choice, especially coupled with some reassurance on sustainable fishing practices such as pole-and-line caught.

Marine Stewardship Council (MSC)

The broad requirements for certification by the MSC are: only fishing healthy stocks, being well-managed so stocks can be fished for the long-term, and minimizing their impact on other species and the wider ecosystem. The MSC certifies a lot of seafood and has received quite a lot of criticism over the years for being too industry-friendly.

For example, a 2020 paper reported that the imagery used in MSC promotional material features a much higher proportion of small vessels and passive fishing gear than the reality of MSC-certified fisheries. That’s hardly surprising (marketing material is not totally accurate?!) but I guess useful to point out.

A scientist from the aforementioned Sustainability Incubator published her findings last year, attesting that there are plenty of human rights abuses aboard boats in MSC fisheries. The MSC responded that they’re not really about human rights – their focus in on addressing overfishing and maintaining healthy fisheries. The FSC added that it does require that a vessel is withdrawn from certified fishery if cited for forced/child labor.

That paper lacks context (e.g., number of violations on MSC-certified fisheries compared to non-certified) and I take the MSC’s point. When I was reviewing the Rainforest Alliance I argued that its protection of rainforests has weakened as it tried to compete with fair trade by including social issues. When it comes to a certification program, I’d prefer to see one thing done right than four things done badly.

The MSC published a dataset on its fisheries in 2025 – the data was also used in a separate paper (also by MSC authors) that examined some fishery stats in the context of MSC certification. The content of these papers is not that interesting but publishing a public dataset is a positive step.

Research published 2019 (including some authors from the MSC) found that 30% of seafood species are mislabeled (e.g., farmed catfish is labeled as cod) but this number dropped to less than 1% when dealing with MSC-certified fish. That’s something!

Friend of the Sea (FOS)

Friend of the Sea was established by the founder of the dolphin-safe label – it’s a partner organization to the United Nations and is based in Milan. The Wikipedia entry for FOS is quite succinct, so I’ll refer you to that for more detail. Briefly, requirements for FOS certification include no overfishing, no disruption of the seabed, no bycatch listed as ‘vulnerable’ or worse in the IUCN Redlist, only certain fishing gear allowed.

While the MSC is more focused on fisheries in the Global North, FOS is more focused on the Global South. The FOS looks to be at least as effective as the MSC – possibly more effective at preventing overfishing. I’ll get into that in the next section.

How effective are the seafood certifications, MSC and FOS?

First I want to quickly mention a 2019 paper that compares the impacts of Fair Trade USA versus MSC certification, concluding that:

Results from this study suggest that Fair Trade USA better aligns with the FAO Guidelines, delivers benefits more quickly to fishing communities, and seems to rely less on national level requirements.

The most useful paper that I’ve found on the efficacy of the MSC and FOS is titled Evaluation and legal assessment of certified seafood. It’s based on independent research (funded by the German Research Foundation) and tackles the core question: how effective are these certification programs at preventing overfishing and the depletion of our oceans?

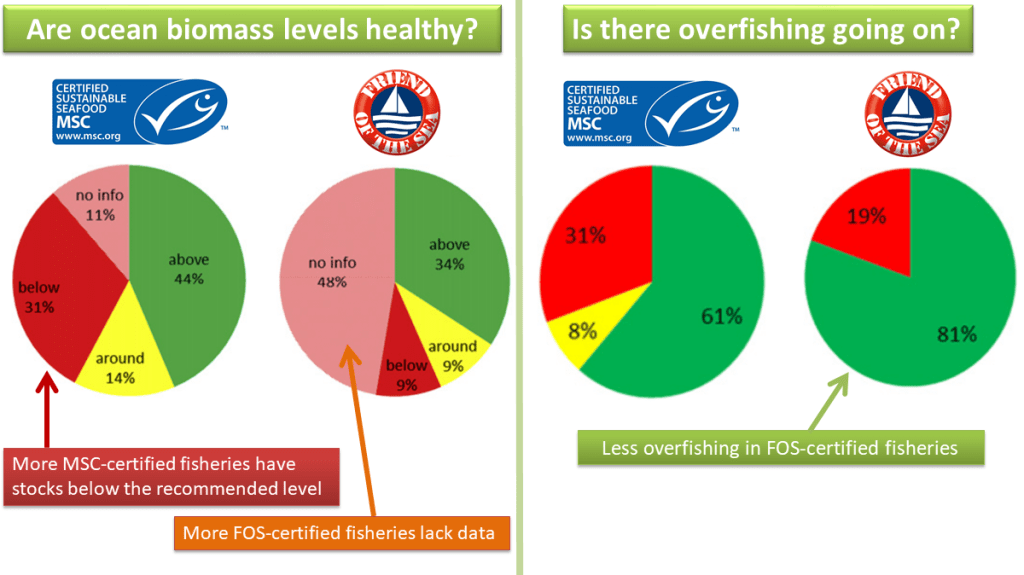

The two pie charts on the left above show that a higher proportion of MSC-certified fisheries are low on stock compared to FOS-certified fisheries. The two charts on the right show that there was more active overfishing going on (at the time of the study) in MSC fisheries compared to FOS fisheries. However, a much higher proportion of FOS fisheries lacked information compared to MSC fisheries (the pink segments in the pie charts on the right).

The authors of the study were quite skeptical of the level of rigor at the MSC:

After reading through over 100 assessments and related documents, we could not help the feeling that these assessors were biased towards bending the rules in favor of their clients.

MSC is financed about half from contributions by donors and half from license fees, i.e., a share of the price paid by the consumers for certified products. Thus, not certifying a fishery or withdrawing an existing certification means less income for the MSC.

In response to a draft of the paper, here’s how the two certification bodies responded:

FOS response: ‘FOS welcomes this external review. Although we do not agree with every single assessment, we decided to critically review all stocks not marked as green and remove FOS certifications if necessary.’’ FOS has meanwhile de-certified three stocks that were marked red in this study. This raises their share of green stocks from 81% to 88% in the FOS pie chart on the right, above.

MSC response: MSC did not provide a comment, but certification was suspended for four stocks as the paper went to press.

Even with all this criticism (particularly of the MSC) the authors found that the proportion of fisheries with healthy level of stocks and a healthy level of active fishing was in the range of 47–69% for certified fisheries, compared to only 15% for all fisheries. Therefore, they concluded that:

It is still reasonable to buy certified seafood, because the percentage of moderately exploited, healthy stocks is 3–4 times higher in certified than in non-certified seafood. – Marine Policy, 2012.

The authors recommend that the MSC and FOS withhold or withdraw certification from fisheries that are actively overfishing. They also recommend that the certification bodies should “be honest with retailers and consumers, e.g. by showing a different label for products from stocks that still need to rebuild biomass.” I don’t think anyone would argue with these recommendations.

Conclusion: support certified fish?

Clearly, the certification bodies can do better. Other papers and reports (e.g., a Greenpeace report on the MSC) generally agree with the conclusion above: certification programs are not perfect but supporting them is better than buying non-certified seafood. There has been much more criticism of the MSC than the FOS (e.g., that it suffers from a conflict of interest) but this difference could be largely due to the fact that the MSC is older and more established.

Based on everything I’ve read, I would give preference to Friend of the Sea (or Fair Trade coupled with some reassurance on sustainability) over the Marine Stewardship Council, but all three have some value (as well as some problems). The FSC may have a slicker logo and website than the FOS, but the latter may be doing better in terms of actual impact.

Before worrying about certifications, though, I think it’s important to take a step back and to think more broadly about the kind of seafood (and its origin) that may be appropriate.

The problem with some seafood guides or certification programs is that they don’t want to exclude or upset any specific industries. I’ll leave you with a helpful paragraph from the California Academy of Sciences post on seafood that will suggests skipping the shrimp and going for some of these options (in the US):

Several fishery stocks are well managed, sustainable, cause little or no damage to non-target species, and by the way, are quite delicious. On that list are the Pacific albacore, yellowfin or ahi tuna, some wild-caught Pacific salmon stocks, dolphinfish a.k.a. mahi mahi, Pacific halibut, primarily those from Alaska, Pacific sardines, mackerels, squids, farmed oysters, mussels, and clams, and Dungeness crabs. Farm-raised catfish, trout, barramundi, Arctic char, striped bass, tilapia, some sturgeon, and some coho salmon are also okay to eat.

Discover more from The Green Stars Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

clear and excellent review!

LikeLiked by 1 person