Some might consider this question to be a no-brainer with maybe the only dilemma being whether we can afford organic items. But to others, including scientists that I’ve worked with, the answer is not so obvious. So I think it’s worthwhile to dive into whether or not we should support organic agriculture. But this time I’m going to try to be brief!

Previous posts on the effectiveness of Fairtrade International, Rainforest Alliance, and the Forest Stewardship Council ran a little long as I wanted to cover as much of the literature as possible to try to clear up any uncertainty. In the case of organic agriculture there’s a ton of literature on the topic, but because there’s less uncertainty, we can actually do this pretty fast! Stick with me!

Organic agriculture: Definition and benefits

A review by researchers at Washington State University summarizes organic practices as follows:

Although requirements vary slightly between certifying agencies, they promote soil quality, crop rotations, animal and plant diversity, biological processes, and animal welfare, while generally prohibiting irradiation, sewage sludge, genetic engineering, the prophylactic use of antibiotics, and virtually all synthetic pesticides and fertilizers.

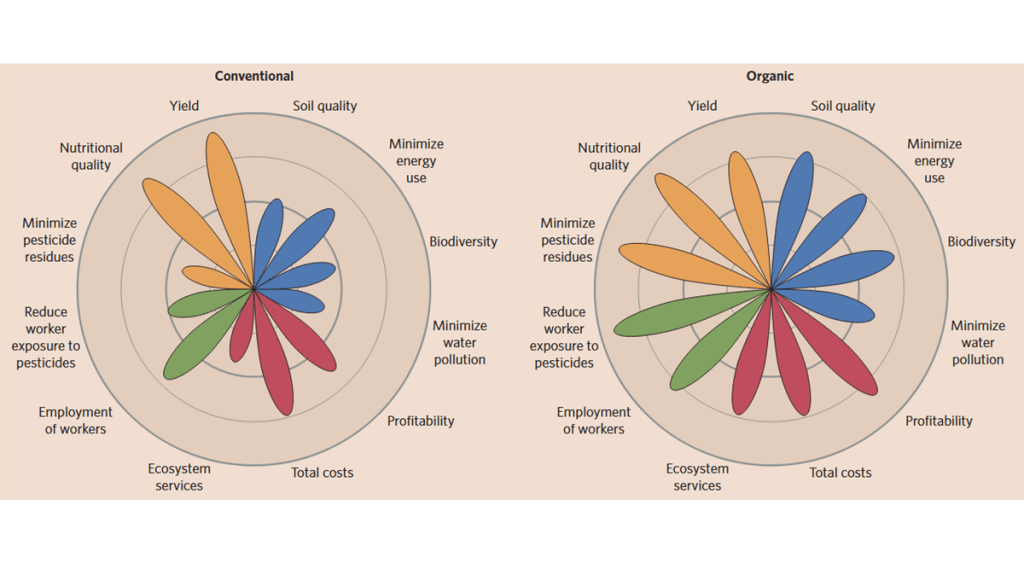

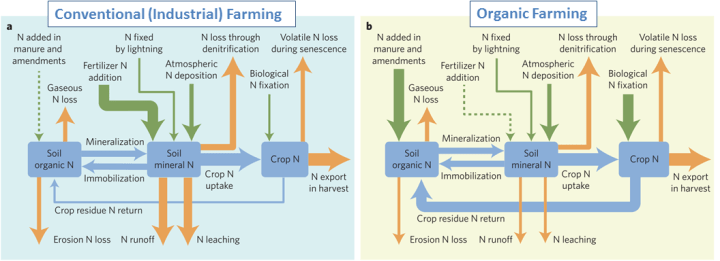

There’s a good scientific consensus that organic farming provides many benefits, improving soil quality, reducing soil erosion, increasing biodiversity, and increasing climate resilience, to name a few. The last benefit – increasing resilience in the face of climate change – is a big one. Industrial farming renders the land more susceptible to crop failure in droughts and also soil erosion from floods while also contributing more to greenhouse gas emissions than organic farming. So it exacerbates the biggest threat to agriculture – climate change – and also our susceptibility to that threat.

While organic agriculture aims to work in harmony with nature as much as possible, industrial agriculture works by suppressing nature using agrochemicals. A top reason for supporting organic agriculture is to avoid the pesticides that industrial agriculture relies on far too much. I’ll refer you to these posts on neonics, and a risk/benefit analysis of imidacloprid (one of the most widely used insecticides). Instead of coating seeds with a cocktail of pesticides, organic farms rely on integrated pest management (IPM) approaches: The prevention, avoidance, monitoring and suppression of pests.

So, is there a problem with choosing organic? Let’s look at organic agriculture’s biggest downside: lower crop yields.

Crop yield gap: Organic versus industrial farming

I’ve previously covered a key science paper on whether we will be able to feed the human population in 2050 without further deforestation. This paper explores a central argument for industrial agriculture: Because crop yields tend to be higher, industrial agriculture could help economize on land use and therefore prevent the further encroachment of farmland into the world’s forests.

In a meta-study co-authored by Jonathan Foley (who went on to start Project Drawdown) average crop yields were found to be around 25% lower on organic farms, compared to conventional farms. (Another meta-study, published the same year, estimated the yield gap to be a little smaller than this – around 20%). Some crops – especially legumes and fruits – fared much than this average, with yields on organic farms similar to those on conventional farms. Fruits do well because many of them are perennial crops, growing on trees, while legumes tend to do well because they fix their own nitrogen. Some annuals, such as wheat do a bit worse than average, with organic yields around 30% lower than conventional.

As the authors of that meta-study point out, one of the reasons why yields of crops such as wheat are higher on conventional (industrial) farms is that excess nitrogen fertilizer is applied – more than the crop can use. This is explained in a post on organic versus conventional bread. The nitrogen fertilizer that’s applied to industrial wheat fields is responsible for 40% of the carbon footprint of conventional bread. But even more critical than this, the nitrogen (and phosphate) runoff into water systems is a huge problem – it’s one of the six planetary boundaries that we’ve now transgressed.

That said, the smaller land footprint of industrial farming could help avoid deforestation to make way for more cropland to feed a growing human population. However, the study on feeding the population in 2050 and other research on food systems and population growth show that there are several ways to avoid deforestation. Here are four of them:

- Reduce our intake of animal products, especially red meat.

- Reduce food waste.

- Stabilize population growth by supporting a better standard of living in the Global South.

- Maximize short-term crop yields using industrial farming practices.

On that first point, see my post on the environmental footprints of meat and other foods. The land footprint of 1 kg of beef is around 90 times larger than the land footprints of either 1 kg bread or 1 kg tofu. Not 90% higher – ninety times higher! This eclipses any difference between the yield gap between organic and industrial farming as to make it almost irrelevant in the great scheme of things. If we cut red meat consumption then we’d have enough land to grow crops whatever way we want and also have plenty of land left over for rewilding and reforestation.

Moving to the second point on the list, food waste is also a big part of the solution. The human population may grow by around 25% by 2050 but we waste around 30% of our food. I’ll address the third point in an upcoming post as I plan to share a chapter from my book-in-progress that’s specifically about population growth. Briefly, by supporting a better standard of living in the Global South (e.g., by buying fair trade certified products) we help stabilize population growth.

So, the top three strategies on the list above all help ensure that there’s plenty of food for the human population without having to encroach on forests. Each of them is also critical to addressing our major environmental threats, including climate change and biodiversity losses. Combining these approaches with sustainable agriculture (e.g., certified organic) also addresses threats such as nitrogen pollution and soil degradation.

Then there is the fourth choice on the list: we continue to adopt industrial agriculture in order to get a short-term 20-25% increase in crop yields. I say short-term as this strategy is not sustainable long-term, due to the loss of pollinators and other essential species, soil deterioration, and vulnerability to droughts and floods. Although the yield gap is initially in favor of industrial agriculture, this changes over time – yields on organic farms are stable and often even improve over the years while industrially-farmed land faces a crisis.

The first three options are win-win scenarios that we should absolutely pursue, while the fourth is definitely not a win-win – it’s akin to running your car into the ground just to get a bit further, rather than taking time out to maintain it.

Criticisms of organic agriculture

Like any of the certifications covered here recently (or anything, really!) there’s room for improvement. Here are a few common criticisms of organic agriculture.

Restrictive rules

One criticism is that the rules of organic agriculture are restrictive and that some kind of hybrid system should exist that combines the best of organic and industrial. I often come across that middle ground when doing my regular shopping – it’ll be produce such as oranges that are labeled pesticide-free. The label (although unofficial) promises that although the farm hasn’t gone the full organic certification route, it does avoid one of the most problematic aspects of industrial agriculture. I guess this is a little bit analogous to fair trade versus direct trade – direct trade coffee isn’t officially certified but the seller makes some promises regarding equity in the supply chain.

But obviously informal labels can be abused and that’s why we end up with a formal third-party certification system – a compromise that took place in America between the pioneering organic farmers and the US Dept. of Agriculture. There are hybrid systems and many developments taking place to improve the efficiency of organic agriculture – I’ll cover them in the last section.

“Big Organic”

That brings us to a second criticism: Thanks to increased demand, we now have “Big Organic” – this was a chapter title in Michael Pollan’s 2006 book, The Omnivore’s Dilemma. As consumers, we sometimes have the attitude of wanting something such as organic agriculture to be bigger and then once it is, we reject it like hipsters, preferring the early stuff. Often, the scale-up of a process makes it more efficient and when we think about feeding the human population in 2050 a certain level of efficiency is required. I like some of Pollan’s writing, but his arguments on this topic are confused.

I thought that Pollan’s desire for a rhetorically useful structure (and furthermore rhetorically useful examples) ruled the book itself — as opposed to the content ruling the structure … As a small-scale organic farmer, I was also disturbed by the inclusion of only two farms … The over-simplified binary here quite honestly pissed me off. – Review of The Omnivore’s Dilemma by an organic farmer.

Pollan gives a couple of examples of organic farms that became big – Earthbound Farm organic greens and Cascadian Farm, which is now owned by General Mills. For the sake of brevity, let me just say this: Of course there’s a gradient of companies and brands, with some better than others. That can be said whether we’re talking about organic foods or any other group of products. Considerations such as how a product is packaged or how far it’s shipped are separate to the debate on organic versus conventional agriculture.

Yes, I prefer to buy organic produce from my local fruit and veg store but not everyone has a great little store or farmers market nearby. And price is a consideration too – I started Ethical Bargains, the sister site to the GSP, to highlight ethical products such as plant-based and organic food that we can access on a budget. Some of the brands that I cover are owned by large food corporations – that’s pretty darn hard to avoid, these days.

I covered Earthbound Farm on Ethical bargains, this week, as an extension of this conversation on Big Organic, so please check that out if you want to read a case study. I’ve also covered Cascadian Farm twice on that blog – the second time looking into the feasibility of the perennial wheat, Kernza. Taking into account multiple factors, including its ownership by General Mills, I scored Cascadian Farm’s organic breakfast cereal 4/5 Green Stars for social and environmental impact. Not perfect but certainly much better than average.

It’s easier when we just put a number on things rather than wringing our hands, unable to decide on anything.

[Instead of encouraging the use of AI here by generating an image, please imagine for yourselves a picture of Beyoncé doing her Single Ladies dance while telling Michal Pollan (who’s wringing his hands) that he shoulda put a number on it. Then feel free to contemplate how AI cheapens and degrades everything!]

The future of organic agriculture

While industrial agriculture is dominated by three agrochemical giants (Bayer, Syngenta, and Corteva), there are many more enterprises, for-profit and non-profit, working towards improving the efficiency and yields of a more sustainable version of agriculture. This does not mean turning away from all technology – on the contrary, it involves replacing the brute force approach of industrial agriculture with a sophisticated and intelligent approach that emphasizes soil health and biodiversity.

Large improvements can come from the adoption of sensors and management techniques that inform more efficient usage of agricultural inputs such as water and nitrogen, especially in the Global South. Traditional plant breeding has brought about most of the improvements in crop characteristics such as yield, shelf-life, and nutritional content, and continues to evolve with technology and demonstrate its relevance.

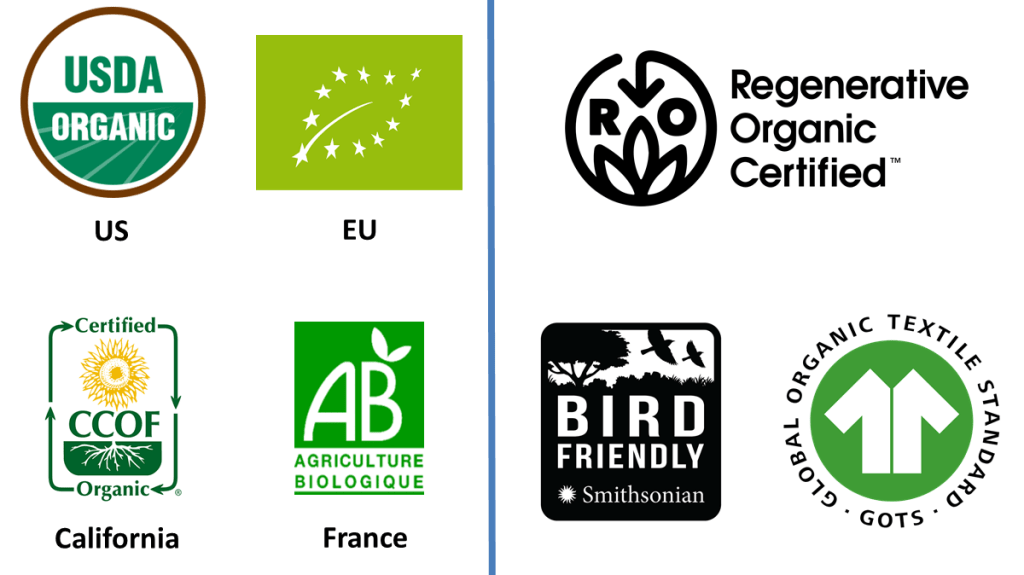

There have been many movements in sustainable agriculture over the years, so the terms can be confusing – organic, biodynamic, agroforestry, permaculture, and regenerative agriculture. But there’s actually quite a lot of overlap between them, with many prioritizing soil health, cover crops, crop rotation, reduced tillage, perennial crops, polycultures, integrated pest management, and preserving biodiversity via land sparing (a portion of land set-aside as a natural habitat) or land sharing (crops integrated into the natural habitat, such as agroforestry).

As far as certifications go, there are variants of organic that apply to specific sectors, such as the Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS) for clothing. This standard stipulates organic farming practices for the growth of raw material but also sets rules for chemical inputs (dyes, treatments) and wastewater management.

But there are also variants that take organic as a baseline and build upon it. A good one is the Bird Friendly certification from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (discussed in a post on Rainforest Alliance) which builds upon an organic certification by adding requirements for shade cover. A more recent development is Regenerative Organic Certified (ROC), which also builds on an organic certification by adding some of the less well defined practices of regenerative agriculture. ROC has a fast-growing list of participants, including Dr. Bronner’s (coconut oil from Sri Lanka), Lotus foods (basmati rice from India), Nature’s Path (oats from Canada), Tablas Creek Vineyards (wine from California), and Guayaki (yerba mate from Argentina).

Bottom line: Support certified organic?

Yes! As a pared-down ethical dilemma of whether to support organic or industrial agriculture, I believe that we should support organic. But we should combine this with a diet that’s mainly plant-based because a global diet of organic food + lots of red meat requires so much land that it threatens rainforests. Prioritizing those two dilemmas: [plant-based vs. red meat] and [organic vs. industrial agriculture], the first one – going plant-based – takes precedence. More on that later – this post is already longer than promised. D’oh!

You can also support sustainable agriculture in a more informal way by talking to your local farmers at farmer markets or through community-supported agriculture (CSA) programs. But when shopping at larger grocery stores, and especially when it comes to packaged products, an official organic certification is helpful – and meaningful.

Discover more from The Green Stars Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A complex issue, indeed, James, and quite a conundrum when it comes to feeding ourselves without more deforestation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It does look complex Rosaline, but once we really examine the options it becomes obvious that industrial farming (war-on-nature style with the full arsenal of agrochemicals) is just not viable. Especially when there are other, better solutions.

Cutting red meat from our diets is the key action to avoid deforestation.

Cheers!

James

LikeLiked by 1 person

I cut red meat from my diet since the 1990s, following my doctor’s recommendation at the time.

LikeLiked by 1 person