Certifications provide one of the more accessible ways to practice ethical consumption. Whether you’re shopping for bananas, a chocolate bar, or a pair of socks, seeing certifications such as fair trade (and/or organic, etc.) should give you some degree of assurance that it’s ethical – right? I’ll focus on the topic of fair trade in this post and since I’m aiming to be fairy comprehensive I’ll give a quick summary now, in case you don’t make it to the end. Fair trade programs, although not perfect, have been repeatedly demonstrated to improve income and quality of life in the Global South.

This is a timely topic for a few reasons. For one thing, Certifications is one of the remaining chapters to write for my upcoming book on ethical consumption (seeking a publisher/agent!). I’m also wrapping up a chapter on water, hence my recent post on how to reduce your water footprint, and will announce the last major chapter in a month or two. Book aside, this topic is highly relevant right now because of the systematic undermining of regulations, environmental protections, human rights, and corporate oversight that is taking place in America.

Why we need third-party certifications

When governments and corporations become too chummy and there’s little oversight over corporate behavior, then third-party certifications become critical. Laura Raynolds, Professor of Sociology at Colorado State University and Director of the Center for Fair & Alternative Trade puts it like this:

Over recent decades globalization has fueled the spread of neo-liberal policies around the world, undermining government regulations in national and international arenas. Deregulation in agro-food sectors – a traditional bastion of government control – has been particularly dramatic.

Note that this quote comes from a paper published in 2007! Well, thankfully we don’t have anything to worry about these days…

But seriously, third-party certification programs provide some assurance that corporations don’t run amok in a deregulated world. They provide a means of communicating to the consumer that a corporate supply chain maintains certain social or environmental standards. Of course, certifications are not a stand-alone solution to all of our social/environmental issues but they can be a valuable tool for deciding which products are worthy of support.

This still requires some research on our part: looking into whether the certification that we plan on trusting is actually effective. A goal of the GSP (and my book) is to do this work for you by providing objective, science-based advice on these topics. So, thank you for reading this – I do appreciate that everyone is stressed to the hilt, but consumer awareness of corporate ethics is more important than ever.

How many fair trade programs are there?

There are several fair trade certification programs, each with a different logo, as shown below. Rather than describing each one, I’ll refer you to the Fair World Project’s guide to the different programs (and the in-depth guide for more detail). To outline the promises of fair trade certification I’m going to focus on the biggest organization: Fairtrade International. It’s denoted by the logos on the left, with FAIRTRADE written as a single word in block capitals.

Fairtrade International logos are shown on the left while other programs are shown on the right. The FAIRTRADE mark on the upper left is used for single-ingredient products, such as coffee or bananas, while the FAIRTRADE logo with an arrow is used to indicate that one or more ingredients of a product is certified (e.g., the cocoa in a chocolate bar). The Fair World Project provides a quick guide to, and an evaluation of, the major fair trade programs, labels, and organizations. The Fair World Project recommends the organizations shown above, with the exception of a “proceed with caution” rating for Fair Trade USA (logo on lower right) which split from Fairtrade International in 2011, causing a stir in the community.

What does a fair trade certification promise?

The most critical features of the fair trade model is that it provides a price safety net as well as a price premium. The commodity market price for crops such as cocoa and coffee can fluctuate wildly – at times dropping to levels that can’t support any kind of living.Fair trade programs help protect against situations like this one, described by a cacao farmer:

The price we could get for cocoa was so low it was not worth harvesting. Many of us abandoned our trees. Some farmers went off in search of work on plantations. It was a very difficult time for us.

Let’s take a look at the standards and objectives of Fairtrade International.

FAIRTRADE International standards

The current Fairtrade International standards aim to achieve the following objectives:

- Set minimum prices for commodities that are based on farmers’ average costs of sustainable production.

- Provide an additional Fairtrade Premium which can be invested in business or community projects chosen democratically by farmers and workers

- Facilitate long-term trading partnerships between producers and their buyers

- Enable greater producer control over the trading process.

- Incorporate human rights and environmental due diligence (aligning with key sustainability legislation).

Most people are familiar with the Fairtrade’s social standards such as the minimum price safety net and the fair trade premium but, in many cases, certification also brings environmental benefits.

Environmental focus areas are: forest protection and deforestation prevention; climate change risk assessment and adaptation; environmental due diligence; minimised and safe use of agrochemicals; proper and safe management of waste; biodiversity; soil health; water protection and efficient water use; and no use of genetically modified organisms.

Fair trade programs can act as a bridge to organic certification by fostering environmental improvements and offering a higher market price for product that is certified organic.

Fairtrade International shows a good level of responsiveness to criticism (which I’ll get to shortly), updating the standards and adapting them to different situations, as appropriate. The organization website contains a library of documents on specific situations (e.g., updates on the scope and benefits of Fairtrade in different regions) as well as broader annual reports.

Total production volumes of Fairtrade International certified products, from the non-profit’s 2023 report.

Social science studies often highlight fair trade in general (and Fairtrade International in particular) as among the best certification programs, in terms of standards. For example, an evaluation of the most common coffee certifications, led by the aforementioned Laura Raynolds, concluded that:

Fair Trade has the strongest social justice standards, while Organic and Bird Friendly certifications have the strongest ecological standards. In contrast, initiatives like UTZ and Rainforest Alliance use standards largely to hold the bar and guarantee minimum requirements in the mainstream coffee industry.

Since then, UTZ and Rainforest Alliance (RA) have merged under the RA label and are now operating according to newer standards, set in 2020. I plan to cover RA in a future post as it’s one of the most common certifications. Raynold’s judgement is echoed in other critiques of third-party certifications: that fair trade is one of the strongest programs, together with organic and the Smithsonian bird friendly label.

The next question is, how well does fair trade work in real life?

How effective is fair trade certification?

The Economics of Fair Trade, a 2014 paper led by Harvard economists, evaluates all major studies published up to that point to make an assessment on whether fair trade works. The authors do a good job at examining the different statistical approaches to figuring out if fair trade certification is beneficial. Here are a few highlights, starting with the main conclusion of this meta-analysis:

There is overwhelming evidence that Fair Trade–certified producers do receive higher prices than conventional farmers for their products.

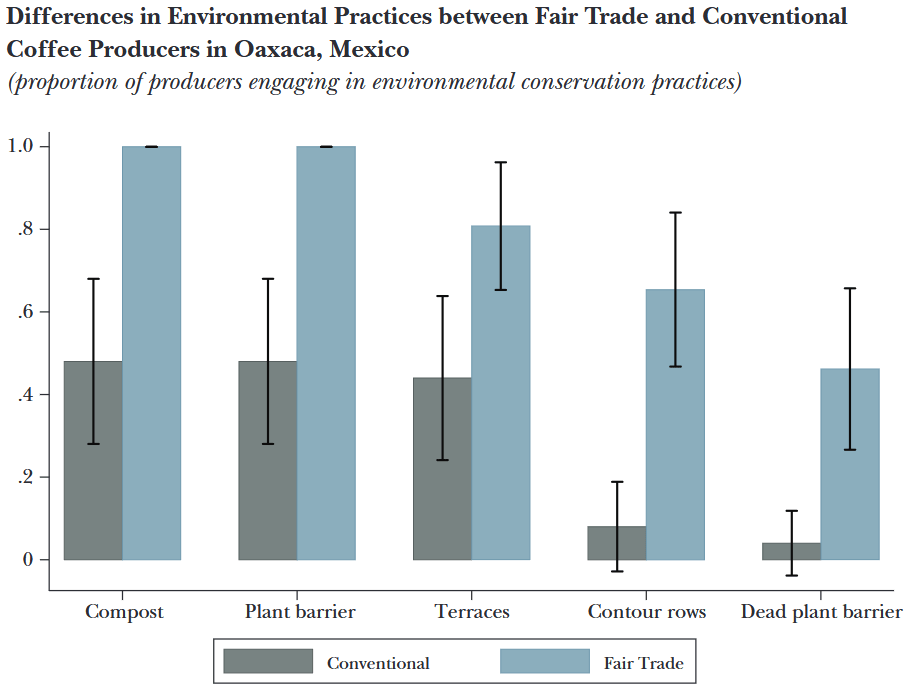

I was surprised to learn how effective fair trade can be at bringing improvements in environmental management.

Among Mexican coffee farmers, there is a strong association between Fair Trade certification and environmentally friendly farming practices

[In Nicaragua,] 43% of Fair Trade farmers had implemented soil and water conservation practices, while only 10% of conventional farmers had done so.

One of the areas with room for improvement is that while farmers almost always benefit from a higher market price, this doesn’t always trickle down to farm laborers. Studies that took place in Mexico, Nicaragua and Costa Rica (summarized in The Economics of Fair Trade) showed that while farmers received more income, laborers came out about the same as laborers on non-certified farms.

Although he finds that the average price obtained by Fair Trade–certified farmers [in Oaxaca] is 130% higher than for conventional farmers (13.22 versus 5.74 pesos per kilogram), the wages paid to hired workers are only 7% higher (47 versus 44 pesos per day).

Although not perfect, the fair trade program was considered by these economists to be more effective than simply giving aid (akin to the old give a man a fish proverb):

In our view, the largest potential benefit of market-based systems like Fair Trade is that they do not distort incentives in as deleterious a way as foreign aid. Instead, they work within the marketplace and reward productive activities and production processes that are valued by consumers and that are good for the local environment and economy.

Another aspect to consider is that fair trade certification can bring broader social benefits to communities that often aren’t being accounted for in studies that focus purely on income.

Broader social aspects of fair trade certification

The broader benefits of fair trade programs to communities are often overlooked in economics or social science studies. First, the fair trade minimum price provides a safety net that’s only obvious during a market downturn, a benefit (of protecting farmers from losing their livelihood) that’s missed by most short-term studies. Second, the fair trade premium is often invested by cooperatives in projects that benefit the whole community (clean water, education, clinics, etc.) but are easily overlooked in surveys of individual laborers. But there have been some studies that investigated the broader social benefits of fair trade certification.

In South Africa’s wine industry 91% of fair trade workers said that the fair trade certification (and their membership in the cooperative) was responsible for improving their living standards. 95% of workers reported that fair trade provided help with education and/or health and 51% reported being helped with both.

Non-certified farmers and workers can also benefit from fair trade activity in their region when community upgrades are funded by the fair trade premium. Studies on the benefits of fair trade can miss this nuance, concluding that certified and non-certified farmers have the same quality of life but overlooking the fact that both groups benefited from improvements brought about by fair trade. Here’s one example of a community benefit that was funded by fair trade:

Dragusanu and Nunn (2014) describe a scholarship program, Children of the Field Foundation, initially implemented in Costa Rica by COOCAFE using Fair Trade premiums. Since its implementation in 1996, the program has provided scholarships to 2,598 students and financial support to 240 schools. COOCAFE estimates that in total, over 5,800 students have been helped by the foundation.

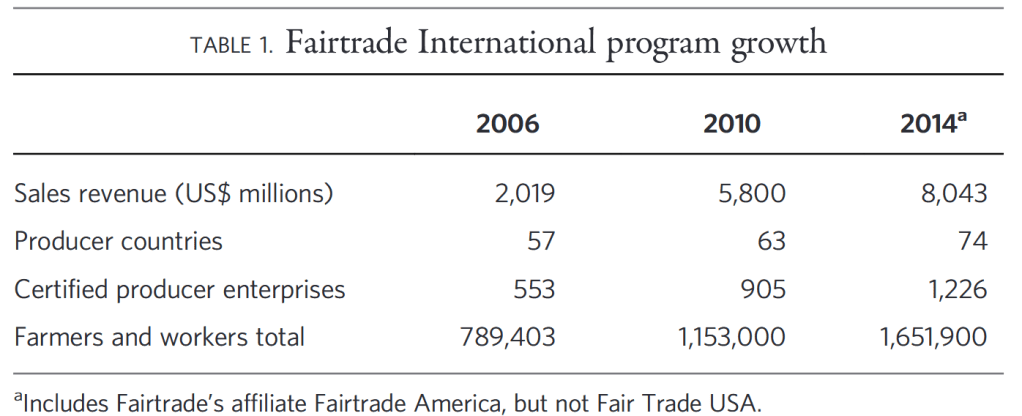

Fairtrade International program growth, 2006-2014, from Raynolds, 2018. (Fairtrade Certification, Labor Standards, and Labor Rights)

The Not Fit for Purpose report

A 2020 report, titled Not Fit for Purpose, attracted a lot of attention by concluding that third-party certification programs aren’t good enough. A few things to note – it’s a report rather than a peer-reviewed publication; the case studies referenced in the report are also not peer-reviewed publications; and it’s published by a non-profit which depends on making a splash to receive funding.

The authors of the report sometimes spun things a certain way when the opposite might actually be the case. For example, they bemoan that farmers have to take on extra paperwork for the certification, and at the same time claim the process is not transparent enough (You can’t have it both ways! – being transparent and compliant requires some record keeping and reporting). Another example is that farmers are selling exactly the same product as fair trade certified and also as non-certified. The explanation of that is pretty simple – the farmer qualifies for fair trade certification and would love to sell it all as certified product, but when the market demand is not high enough (as is often the case) then a farmer can only sell a portion of their product as certified.

So, basically I don’t think the report is particularly rigorous. But having said all of that, fair trade comes across much better than other programs in the report. Here are some highlights to that effect:

Only three of the seven MSIs we analyzed (Fairtrade International, FSC, and MSC) explicitly require compliance with international human rights or international labor standards, and on a very narrow range of issues, such as child and forced labor or the other ILO core conventions. [MSI = multi-stakeholder initiative; FSC = Forest Stewardship Council, MSC = Marine Stewardship Council]

Of the eight prominent supply-chain MSIs we reviewed for this chapter, only two explicitly recognize the need for responsible purchasing practices: Fairtrade International and the Fair Labor Association

One criticism in the report that does apply to Fairtrade certification is that the cost of certification is sometimes too much for producers to be able to absorb (i.e., when it’s not covered by the extra premium income). Clearly that only applies in a minority of cases – nobody would apply if a majority lost money by joining the program. It also sounds more like a bug to be fixed than an ethical flaw in the system. Also Fairtrade International specifically prefers producers to be organized as cooperatives, sharing the cost of certification.

Another criticism is based on reports of violations of standards, such as tea pickers paid a pittance. These cases have to be put in context – how many violations are there as a percentage of certified farmers, and is this offset by benefits for many others? Peer-reviewed publications are evaluated by experts in the field on technical aspects on the work such as statistical approaches. Reports are not subject to these oversights. I’ve no doubt that violations occur with any certification program, but they need to be put in perspective and balanced against positives. There may be some certification programs where the positives don’t outweigh the negatives (e.g., RSPO for palm oil) but for Fairtrade International, the opposite is true – it’s beneficial on the whole.

Although the Not Fit for Purpose report is flawed, it still serves a purpose of drawing attention to issues that need to be investigated further. Oversight and a healthy level of criticism is a good thing when they help keep an organization accountable. Of course improvement is needed for any program such as Fairtrade International that has ambitious goals and many challenges in execution.

Recent peer-reviewed publications on fair trade

I’ll wrap this up by highlighting some of the research since The Economics of Fair Trade that examine the efficacy of fair trade. A 2018 paper on the well-known partnership between Divine Chocolate and the Kupoa Kopoo cocoa farmer’s cooperative in Ghana concluded that:

The Divine – Kuapa Kooko partnership, which implemented a clear resourced gender equality strategy, has made a positive contribution to reducing inequality, empowering women cocoa farmers and improving their rights.

Two recent studies on the impact of Fairtrade certification on cocoa famers in Côte d’Ivoire were overseen by Matin Qaim, a respected German professor of agricultural economics.

First, a 2019 paper in Nature Sustainability reported that Fairtrade certification leads to definite improvements for cooperative members such as higher wages and improved worker welfare. The group also concluded that that wages and working conditions for farm laborers are not affected by Fairtrade standards.

Cooperative workers benefit from Fairtrade certification whereas farm workers do not. Fairtrade increases the annual wages of cooperative workers by about 160%, raises the likelihood of receiving at least the minimum wage by 59 percentage points and reduces the likelihood of living below the poverty line by 35 percentage points

Fairtrade increases the likelihood of having a written contract by 62 percentage points for cooperative workers. Compliance with labour standards at the cooperative level is typically closely monitored during Fairtrade inspections

Fairtrade has recently undertaken efforts to better understand and address labour issues in the small farm sector, which seems to be an important step.

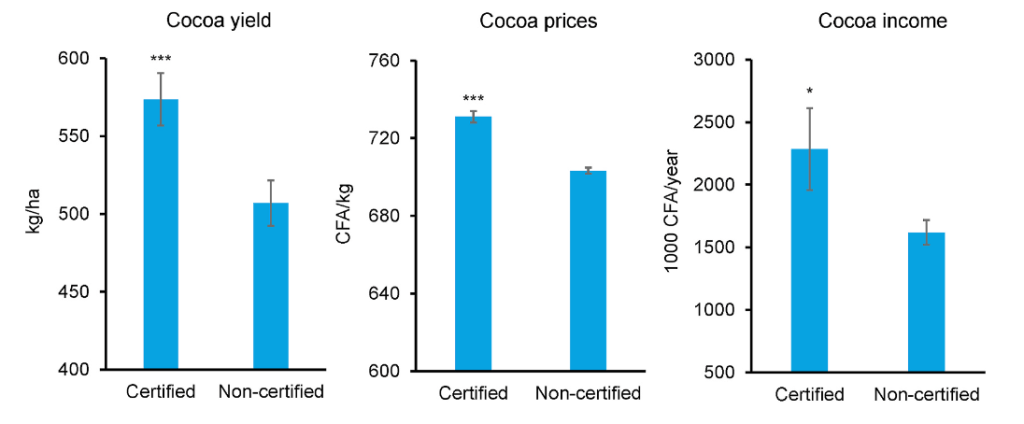

Two years later (2021) Prof. Qaim’s group published results of another study that also focused on cocoa in Côte d’Ivoire. This study also found that income from cocoa farming was significantly higher for Fairtrade-certified farms (see figure, below) but they also specifically looked at the impact of certification on the poorest households.

In comparing the poorest households to the average, the economists found that, “Fairtrade increases living standards with over-proportional benefits for poor households.” Or, to be more exact:

Regression models with instrumental variables suggest that Fairtrade increases aggregate consumption expenditures by 9% on average. For poor households, the effect is even larger (14%).

In her most recent paper on the topic (focusing on the flower industry in Ecuador) Laura Raynolds shows that fairtrade certification brings definite benefits: “has significantly increased individual empowerment”

Funding [from the Fairtrade premium] goes largely to educational, health, and low-interest loan programs. Surveyed workers credit the Fairtrade Premium with significantly improving their well-being, with 96% participating in capacity-building activities, 89% accessing medical services, 59% accessing loans, and 38% accessing scholarships.

She states that “Fairtrade is one of the few certifications to rigorously support freedom of association and require worker representation,” but that progress is limited by “competition from supermarket labels and business-friendly certifications with negligible buyer standards.”

So you can definitely say that it comes down to us – consumer demand for Fairtrade certified products is the main driving force for success of the program. In many industries examined over the last couple of decades the potential supply of fair trade certified product is greater than the consumer demand.

Conclusion on the effectiveness of fair trade certification

Virtually all of the evidence indicates that Fairtrade certification brings significant benefits to farmers and communities. An area for improvement is to extend to greater benefits for hired workers although at least one study showed that certification does particularly benefit the poorest households. Fairtrade International appears to be responsive to criticism and willing to improve.

In an earlier GSP post on coffee that compared fair trade to direct trade I basically said that both can work. You’d have to do a bit more work to figure out if a coffee claiming direct trade is actually benefiting producers. Laura Raynolds divided fair trade coffee into three categories – mission-driven, quality-driven, and market-driven. Her conclusion:

Fair Trade’s sharpest challenge comes from the entry of market-driven buyers who vigorously pursue mainstream business norms and practices. Dominant coffee brand corporations limit their Fair Trade engagement to public relations defined minimums, using the [fair trade] label to position themselves and their products within the market.

I would agree – fair trade is best supported by buying from companies that are also mission-driven rather than just a small side-product for a mostly unethical brand. For example, seek out products from an Alternative Trading Organization (ATO) – a mission-driven business aligned with the fair trade movement. Three examples are Equal Exchange, Alter Eco and Divine. And certainly don’t get duped into thinking that in-house programs and logos (e.g., Mondelez’s Cocoa Life) are a replacement for independent multi-stakeholder initiatives such as Fairtrade International.

Choosing products that are certified fair trade (or reputable direct trade) and organic is still one of the most effective ways to cover the social and environmental bases.

Discover more from The Green Stars Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Fair trade programs are very useful! Well shared

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Priti!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nice article! What I miss is that Fairtrade can also increase costs for input. So that a gain in yield and e.g. cocoa income might not translate into overall higher household income.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment. Studies do confirm higher household income for farmers but of course there are probably a few cases where it’s borderline. Note that the outcomes are usually better for small farmers under Fairtrade International than with Fair Trade USA.

LikeLike