How should we think about ethical products when they are owned by multinational corporations with poor ethical track records? This question comes up many times when I review products and in comments on the blog, so I think it’s worth taking another look at it. I’d also like to hear your opinion on it, via the survey at the end of the post and/or a comment.

In some cases, brands claiming to be ethical or sustainable are established by multinational corporations and, in my experience, these brands are more likely to be greenwashed. But, more often, a company with a good reputation is bought out by a larger corporation. Here are a few examples, recently examined in the GSP’s sister site, Ethical Bargains:

- Silk vegan cream, owned by Danone

- Hu chocolate, owned by Mondelez

- Cascadian Farm cereal, owned by General Mills

In my opinion, the best way to deal with these dilemmas is with numbers – in other words, decide on an ethical score for the product in question. Your score will just be an estimate, of course, but I find that the practice of coming up with a number helps to keep everything in perspective rather than getting caught up in one or two details. A goal of the Green Stars Project is to encourage you to get into the habit of doing this on a regular basis and to share your scores online so that this practice becomes the norm.

So in terms of ethical scores, the question posed at the start of this post could be expressed as follows:

How would you adjust your ethical rating of a product when the parent company is less ethical?

Let’s say, for example, there’s an ethical product that would have scored 5/5 Green Stars for social and environmental impact when it was an independent company (i.e., it’s in the top 10%, in terms of ethics). Then it’s bought by a corporation that you would score 1/5 Green Stars (i.e., bottom 20%). How would you adjust the score of the ethical product, if at all?

Here are some factors to consider before deciding:

How else do we expect corporations to improve?

When we look at large corporations with poor track records on social and environmental issues, what do we want to happen in an ideal future scenario? Do we want the largest multinationals to disappear, replaced by smaller ethical companies? That would be nice, but most of these corporations are well diversified and will adapt to market forces.

This adaptation is not a bad thing – ethical consumption works via the market forces of supply and demand. For example, if a massive trend swept through society to largely avoid bottled water, the multinationals that contain a bottled water division (which includes many of them) would adapt. They would focus on other divisions, other products, and would most likely survive this hiccup.

One of the examples I listed earlier is vegan dairy brand Silk, now owned by Danone, a French multinational that dominates the dairy products category. As you probably know by now, we need to replace meat and dairy with plant-based alternatives if we have a hope of avoiding severe climate change, deforestation, and global food shortages. If we were to devise a plan for Danone to improve ethically, it would be to move away from dairy towards plant-based alternatives.

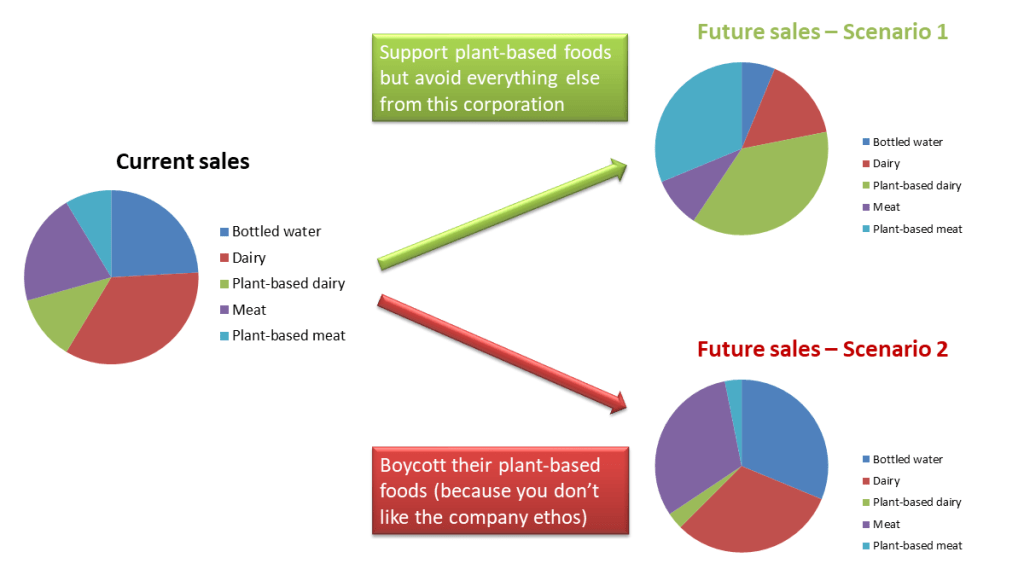

So, you could say that there are two ways of looking at plant-based dairy brands such as Silk (in the US) or Alpro (in Europe) that are now owned by Danone. One is to say that because Danone supports intensive dairy farming, etc., that all of its brands (even the vegan products) should be avoided. The alternative view is that we should support these vegan brands and thereby encourage Danone to invest further in plant-based foods.

I lean towards the second view. Danone will only produce dairy products (from intensive farms) as long as people buy them. Similarly, the company’s venture into plant-based alternatives will only continue as long as customers support it. Boycotting the plant-based brands will only drive the company back towards conventional, intensive dairy.

To labor this point a little, companies will only make what we buy and therefore we collectively guide the direction of multinational corporations with our purchase decisions. Danone is the second-largest producer of bottled water on the planet and although we haven’t yet given up bottled water, en masse, the percentage of Danone’s revenue from bottled water has at least slipped from 19% in 2018 to 16% in 2022. It’s gradually transitioning from a company that makes money from dairy and bottled water to one that makes money from plant-based dairy alternatives – but only if we nudge it in that direction.

What about the employees of the acquired company?

When a company is acquired by a large multinational corporation, this is largely a decision made between the CEOs and boards of directors. The employees rarely get a say in the decision and I think it’s worth considering them in all of this. For example, when Whole Foods was acquired by Amazon, my heart broke a little for the employees. They worked for a company they believed in because of its reputation for stocking ethical products, only to find, one day that it has been bought by a corporation that many of them had little respect for.

Many of the companies had a long history before acquisition – plant-based dairy brand Silk was founded in 1977 in Colorado while Alpro began in 1980 in Belgium. I discuss a few others in a post that’s a prequel to this one: should you always support vegan brands? For example, Sweet Earth has been making vegan foods in Northern California 1978 before being acquired by Nestlé in 2017. I don’t have much love for Amazon or Nestlé, but I will sometimes still shop in Whole Foods or buy Sweet Earth products as long as they haven’t compromised significantly on ethics since acquisition.

The leadership of smaller companies often justify selling to a larger corporation as a means of increasing the distribution of their products. This is a valid reason in some cases – more so for Sweet Earth than Whole Foods – and the owner/founder of a company does of course have the right to sell. But the employees and suppliers to the company weren’t likely to be part of the decision, so should they be punished?

That’s all as long as the acquired company keeps on doing what made it good in the first place. If the brand changes significantly for the worse then all bets are off. For example, if Hu Chocolate ceased to purchase organic, fair trade ingredients and instead switched to the Cocoa Life logo of its parent company, Mondelez, then the brand’s ethical rating would drop significantly. It would slip from better than average (>2.5 Green Stars and therefore worth supporting) to worse than average (< 2.5 Green Stars and not worth supporting). Hu has maintained its certifications so far, but this is always something to keep an eye on if you decide to continue supporting the brand.

Closing thoughts

It sounds like I’m steering us towards a decision to support ethical products from mediocre multinational corporations. Well, I do believe that we should prioritize ethical products from smaller, independent companies – especially for products from the Global South, where smaller companies are better positioned to avoid commodity market supply chains. But at the same time, I think that it’s not helpful to avoid ethical brands because their parent company is engaged in dairy, meat, bottled water, etc. Instead we should avoid the unethical products (obviously!) but also encourage any steps on the right direction.

Also, depending on where you live, you may have a pretty limited number of options when it comes to ethical products such as plant-based foods. Considering that choosing plant-based foods is the most critical action for many consumers and factoring in time remaining for us to adopt these changes, the widespread delivery that multinationals can achieve is a necessary part of the solution.

Should the ethical score of a product be reduced a lot because the parent company is engaged in quite a bit of unsustainable / unethical business? To take an example, I had originally scored Silk organic soy milk 4/5 Green Stars for social and environmental impact, more or less taking off 1 star because of ownership by Danone.

Recently I wondered if this wasn’t actually too harsh and actually adjusted the score to 4.5 out of 5 Green Stars. The milk was made from organic soybeans sourced from North America and not much else, besides some added vitamins and minerals. Milk make from legumes (soybeans, pea protein, bambara groundnuts, etc.) is not just a little bit better than dairy – it’s a more sustainable option by far.* Coupled with that, you could argue that supporting Silk supports a move away from intensive dairy farming by Danone.

*I’ll do a post in the near future with some numbers comparing different animal products as it’s very useful to know how they all compare: eggs, dairy, fish, chicken, beef, etc.

Survey – how do you feel about ethical brands owned by multinationals?

For the survey below, imagine that you’ve found an ethical product such as organic soy milk but then discovered that the brand is owned by a multinational such as Danone, Mondelez, General Mills, etc. (i.e., a corporation that’s worse than average, ethically speaking).

Also, please feel free to comment below with your opinion.

Thanks for reading! If you are interested in ethical consumption, climate change, food sustainability, plant-based food, etc., consider visiting my other blog, Ethical Bargains, which evaluates products for social and environmental impact. In recent posts on Ethical Bargains, I examine Tindle vegan chicken tenders and a couple of Australian wines.

Discover more from The Green Stars Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You make some interesting points, here. One issue is taking the time to research the products, especially since the facts may be somewhat hidden. Overall, the main problem that bothers me is that the ethical and plant-based products are almost always much more expensive!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for your comment, Becky.

You bring up a valid point. Here’s a quote from The Vegan Society, the British organization behind the Vegan Trademark:

Another way to look at this is that the cheapness of certain things (e.g., commodity chocolate, fast food burgers) comes at a great social (e.g., poverty in West Africa) or environmental (e.g., deforestation) cost. We need to get used to buying fewer, higher-quality things so that the price difference does not make such a big deal to our budget.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for that additional info!

LikeLiked by 1 person