You’ve no-doubt read or heard something about the perils of “ultra-processed food” (UPF) by now. If not, I’ll save you some time: Basing your diet predominantly on the kind of food you’d buy at the 7-11 store is not good for your health. In this sense, the discussion on UPF is basically a new way of talking about something we already knew. My issue with it, which I will cover over the next two posts, is that the conversation on UPF has become a front line in the war against plant-based food.

Following the conversation on UPF has been a slog, to be honest, because the science is often flimsy and media articles are often inaccurate, but I’ll share one useful finding. In a study, published in Psychiatry last year, Harvard scientists found a significant association between artificial sweeteners and depression. This is useful information that warrants further investigation, but the finding is not really related to the level of food processing – it’s related to a specific food ingredient. And long before the term ultra-processed food was coined, nutritional studies have informed us when certain ingredients are problematic – trans-fat, high sugar content, etc.

I love learning about nutrition (I did my PhD in an institute that specializes in nutrition) and have written on that topic several times here on the GSP. Perhaps my most critical learning, from both sustainability and human-health standpoints, has been that a high-meat, low-carb diet will shorten your lifespan.

A low-carb diet can be in alignment with both health and the planet if it’s plant-based (e.g., rich in legumes). But a diet that includes a good amount of carbohydrates (around 50% of your calories) is typically the best option for both your health and the planet. – Sustainability and health benefits of carbs.

And of course we also know that the healthiest carb-rich foods are whole foods such as veggies and whole grains. We don’t need the discussion on UPF to tell us to avoid refined sugary foods such as soda and donuts. With all that considered, what are we actually learning that’s new, when we talk about ultra-processed food?

I wouldn’t particularly care about the ineffectiveness of UPF as a research tool (a way of categorizing our food) except that it has become one of the most effective marketing tactics for the meat and dairy industry. To illustrate how this is playing out, I’m going to take look at the latest high-profile research study that made headlines around the world. I’m happy to look at further examples if there’s interest, but this is a perfect case study to start with.

Impact of plant-based UPF on cardiovascular risk

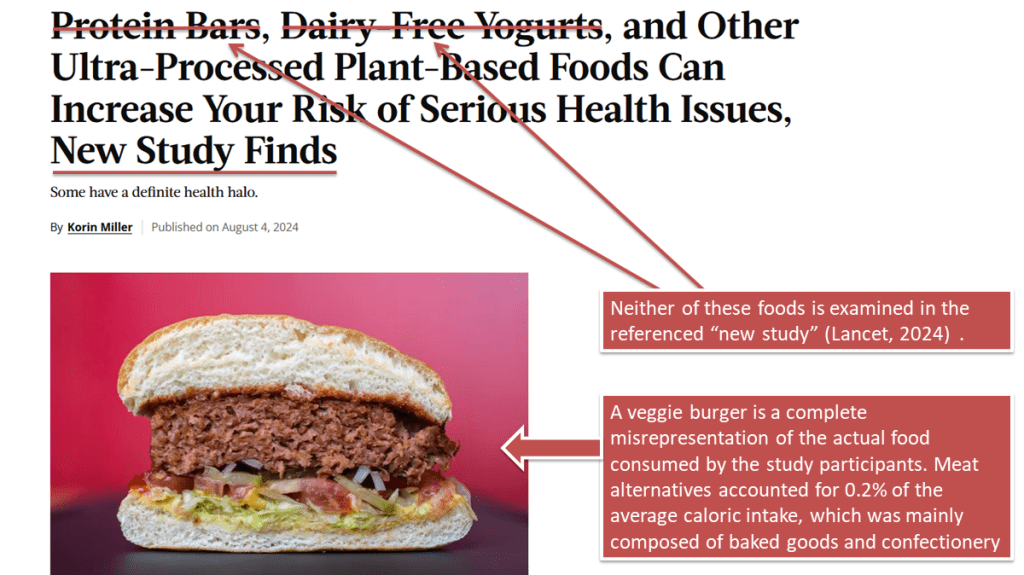

A paper on the impact of, specifically, plant-based UPF on heart disease was published in The Lancet in July 2024. It first came to my attention through an article by Korin Miller in Food & Wine (owned by Time, Inc.). Take a look at the article’s headline:

“Protein Bars, Dairy-Free Yogurts, and Other Ultra-Processed Plant-Based Foods Can Increase Your Risk of Serious Health Issues, New Study Finds.”

The main image for the story was a photo of a plant-based burger.

This sounds pretty bad, right? The main takeaway for readers is that plant-based food can cause serious health issues, and it’s based on research published in The Lancet. Here’s a key quote from the article:

In the plant-based category, snacks and convenience foods tend to be the most likely to be ultra-processed, Keatley says. But many plant-based burgers, sausages, nuggets, and protein bars are also problematic, per Cording.

Cording and Keatley, both registered dietitians, crop up regularly to provide quotes in Miller’s articles, in which they invariably receive plugs for their respective book and business. Neither is connected to the Lancet study.

Protein bars are not actually mentioned in the Lancet paper, nor are dairy-free yogurts – and yet they lead the article headline. In reality, the “new study” has nothing to say about these foods.

What about the plant-based burger, also mentioned by Cording and selected as the featured image?

Let’s take a look at the Lancet paper itself, titled:

Implications of food ultra-processing on cardiovascular risk considering plant origin foods: an analysis of the UK Biobank cohort.

The term “plant origin foods” suggests that the paper will deal with the plant-based products that can replace meat and dairy. There is also a prominent mention of meat substitutes in the introduction to the paper:

Modern plant-sourced diets may incorporate a range of ultra-processed foods (UPF), such as sugar-sweetened beverages, snacks, confectionery, but also the ‘plant-sourced’ sausages, nuggets, and burgers that are produced with ingredients originating from plants and marketed as meat and dairy substitutes.

Notice how this is almost exactly mirrored by the quotes from the two dieticians in the Food & Wine article.

So, actually, there is some judgement of plant-based meat substitutes in the paper’s introduction, which could well have prompted some journalists to focus on this. Plant based meat substitutes are specifically called out with a “but also,” as if to say they are perhaps more important than the sodas, snacks and confectionery. It’s like an academic version of clickbait and is mirrored by many news articles on UPF that use the more overt trope: The last one will surprise you!

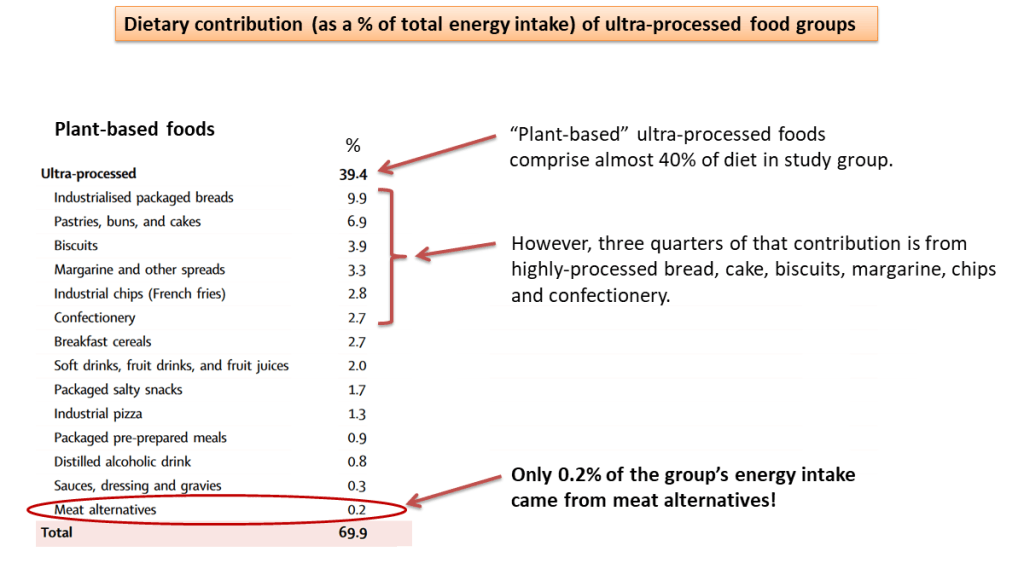

Calling out meat substitutes in the introduction would be fine if the paper had anything to say about them – I mean the actual data in the paper – and this is where things really get interesting. Here’s a breakdown of the ultra-processed foods consumed by participants in that study:

The amount of meat alternatives consumed by the study participants makes the smallest contribution to caloric intake. At 0.2% of total calories consumed, it’s almost negligible. The “plant-based UPFs” that the study actually examines is 75% comprised of pastries, biscuits (cookies), chips (fries) and sweets (candy!). These are certainly the kinds of foods (high added sugar, high fat) that we connect with heart problems but they are not what you would call “plant-based food” in the normal sense of the term (i.e., meat and dairy alternatives).

And yet, for a study that examined a diet consisting of almost zero plant-based meat, here’s what the authors have to say in the discussion section of the paper:

[One study] revealed that vegetarians and vegans consumed more UPF than meat eaters, primarily through the consumption of industrial plant-sourced meat and dairy substitutes. Emerging evidence has shown many harmful health effects associated with UPF consumption, this study provides evidence for the first time that the impact of plant-sourced UPF on cardiovascular disease should not be overlooked.

There is a clear implication here that plant-sourced meat and dairy substitutes are harmful. But since the authors provide absolutely no evidence to support this, the implied message is carefully delivered via two carefully juxtaposed, legally defensible statements.

In case the message isn’t fully received, the final sentence of the paper’s conclusion is this:

Future research and dietary guidelines promoting a plant-sourced diet should emphasize not only the reduction of meat, red meat, or animal-sourced foods but also the need to avoid all UPF.

Avoid all UPF – in other words, sure you can switch to a plant-based diet but you’d better not eat meat substitutes. All they are missing is a final, good luck with that, you damn hippies!

Again, there’s a strong implication here that this study has demonstrated that the consumption of plant-sourced meat and dairy substitutes has harmful health effects and increases the risk of cardiovascular disease. Let me state categorically – the study provides no evidence for this, unless the meat alternatives that we are talking about are cake and biscuits.

There is clearly a large discrepancy between the diet that the authors depict by the language used in the paper, quoted above, and the actual food consumed. Take a look:

Also note that the category of “plant-based” UPF includes plenty of items that contain animal products (they are just “primarily plant-based”) – cake and pastries made with eggs and butter, pizza topped with cheese and meat. In fact, these are the very animal-based ingredients what we tend to associate with cardiovascular disease – and yet they are in the plant-based column!

It’s worth mentioning again at this point that this paper was published in The Lancet – one of the most reputable journals in medicine. There is a tendency to simply trust a paper’s messaging because of the journal’s reputation, but sadly that’s not so straightforward these days, particularly in the field of nutrition. Marion Nestle (Professor Emerita at NYU and a legend in the field) has her hands full examining nutrition papers that have been funded by various food industry groups on her Food Politics blog (here’s a recent example). I’ve also discussed this topic in a post on the excellent book, Proteinaholic.

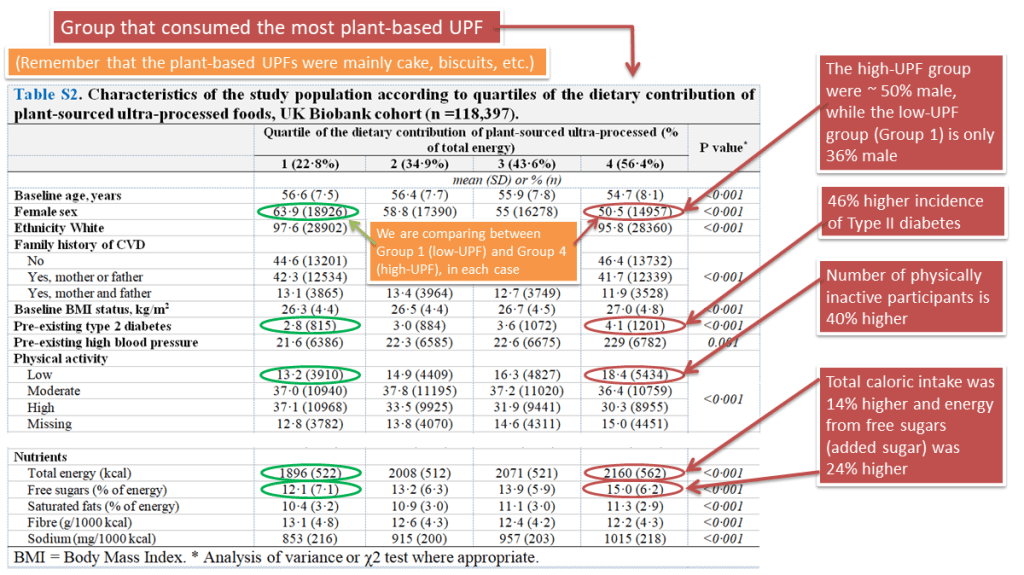

There’s another thing that I want to point out: reporting on the study participants is confusing / misleading. In the paper, various stats on the study participants (age, gender, etc.) are shown in Table 1 – and they are divided into four groups based on how much plant-sourced non-ultra-processed foods they consumed. Why would they show participants grouped by how much non-UPF food they consumed when the paper specifically looks at the impact of consuming UPF?

The more relevant data (available the paper’s supplementary data, often ignored by readers) is show below with some annotations. The study participants who consumed the most plant-based UPF were very different (in terms of cardiovascular disease risk factors) to those who consumed the least. There were significantly more physically-inactive males, for example, in the high “plant-based UPF” group.

The authors do comment on these differences and say that they were “adjusted for” in the data analysis. Then why not show the data in the main paper? I want to make two points about this:

- Adjusting for confounding factors such as physical activity in nutrition studies is notoriously difficult. This is why it’s hard to demonstrate causality in diet studies – especially when (as is the case here) the data was not collected to answer the specific question that the authors are asking. When there are multiple, large confounding factors (as is the case here) it becomes even harder to adjust for them and reach a meaningful conclusion.

- Seeing how the two groups (low-UPF versus high-UPF) differ – for example, that the high-UPF group consumed 24% more sugars in their food – is a reminder that the “plant-based UPF” consumed by participants was mainly sweet, baked items, not meat alternatives!

The authors use language that portrays the image of a person transitioning to a plant-based diet, implying risks connected to eating meat substitutes. But the actual “high plant-based UPF” group was distinguished by a higher proportion of physically-inactive males who ate a lot of cake, cookies, fries and other sugary/fatty foods.

Let me be clear – I’ve no problem with science calling out the hazards of junk food, or with any well-designed study on nutrition. But this paper has nothing to say about meat alternatives in terms of scientific content, but with a few strategic sentences it hints that it does. And what do the media pick up on?

Update: I found that the media press kit that was sent out with the paper deliberately misled journalists into thinking the paper is related to meat alternatives.

The press release also emphasized that interpretation, specifically stating in the first paragraph that products “intended to replace animal-based foods”—such as plant-based sausages, nuggets and burgers—were linked to the higher risk for cardiovascular illness. – Scientific American

So actually the story looks more like this:

The more I look into this the more it looks like the bulk of responsibility lies on the shoulders of the paper’s authors (and the Lancet). At the same time, good journalism involves fact-checking, and an examination of the paper in any detail would have revealed this large discrepancy.

Lancet paper authors include the originators of the NOVA system to classify UPF

I was surprised to see that this Lancet paper was co-authored by two of the main people behind the conversation on UPF. Carlos Augusto Monteiro (University of São Paulo) brought the term ultra-processed food into vogue with a 2009 commentary. Another author on the Lancet paper, Maria Laura da Costa Louzada, worked with Monteiro to devise the NOVA system, which classifies our food into four categories that range from unprocessed to UPF. In this system, meat is classified as unprocessed while plant-based alternatives such as seitan and tofu are considered to be ultra-processed.

All of this is deeply concerning to me and raises serious questions regarding the intentions behind the UPF conversation.

In the next post I’ll cover the broader picture of UPFs and the NOVA system.

Afterword

When I became vegetarian in the late 1980s there weren’t many options. In fact, I ate fish for the first few years and when the 1990’s rolled around I was delighted to be able to buy products such as Quorn that replaced meat in recipes. As a microbiologist, I understood how Quorn is made and applaud that we have found smart ways to sustainably feed ourselves. We should be grateful that much of the world’s population (mainly in Asia) has traditionally followed a vegetarian or mostly-vegetarian diet, relying on traditional products like tofu and seitan to add variety to their meals. Otherwise, climate change would be so severe by now that I probably wouldn’t be here writing this, with hope still in my heart.

Discover more from The Green Stars Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This terrifies me on one level while angering me on another.

Funnily, an hour or two before your post dropped into my inbox, I was complaining to a vegan friend that the algorithms on my social media feeds had suddenly gone wonky presenting me with meat-eating ads and anti-plant based reels. Now, reading your research, I see what my gut suggested – there is a concerted effort to discredit “us”.

J, I am SO over conspiracies, flawed research, and no credential experts. Mind, some of those in this paper you’re citing have expertise, of course. Still, they’ve not taken care to ensure their colleagues are presenting their findings correctly. Cheap ploys to “sell” have been around for ever, I’m just especially sick of it.

One question I have is, if seitan and tofu are demonized, why not cheese – or maybe cheese is listed as an UPF?

Anywho, bravo as always. I don’t know how you stay positive. 😜

Take care,

F

PdotS: you referenced a Lancet article 2025… was that a typo?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear F,

Thanks for your thoughtful comments (and spotting the typo!). Your instinct is correct about cheese: it is actually not categorized as ultra-processed, while tofu is! This certainly tells us something about the motivations behind the UPF conversation and NOVA classification system. It’s actually the subject of next Sunday’s post, so congrats on anticipating that!

Yes, it’s hard not to be triggered by all of this – especially when it’s in your news or social feeds every day. I look forward to a change in topic (although the new topic may be the US election – out of the frying pan and into the fire!).

And you’re totally right – it’s possible that some authors on the paper were not aware of any agenda. It reminds me of a paper claiming that the bestselling pesticides known as neonics pose no threat to bees. The paper’s first author had failed to disclose his prior funding from Syngenta, Monsanto, Bayer CropScience, Dow AgroScience, and Pioneer/DuPont. However, the last author on the paper (Dr. Jeff Pettis, a senior USDA scientist) was demoted after testifying to congress that the insecticides are harmful to bees. Pettis has since left the USDA and is now president of Apimondia, the International Federation of Beekeepers’ Associations.

So I guess the lesson is to channel the frustration into something positive!

J

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also, not sure if you’re seeing my comments as I’m not seeing them. Can you let me know? Of course, if you don’t see them you’re not likely to reply. LOL.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi F,

Yes, I saw your comments – thanks for checking! They require approval before they are visible on the site.

I responded to your main comment, above.

Cheers!

J

LikeLike

Thank you for your attempts to clarify this topic!

LikeLiked by 1 person