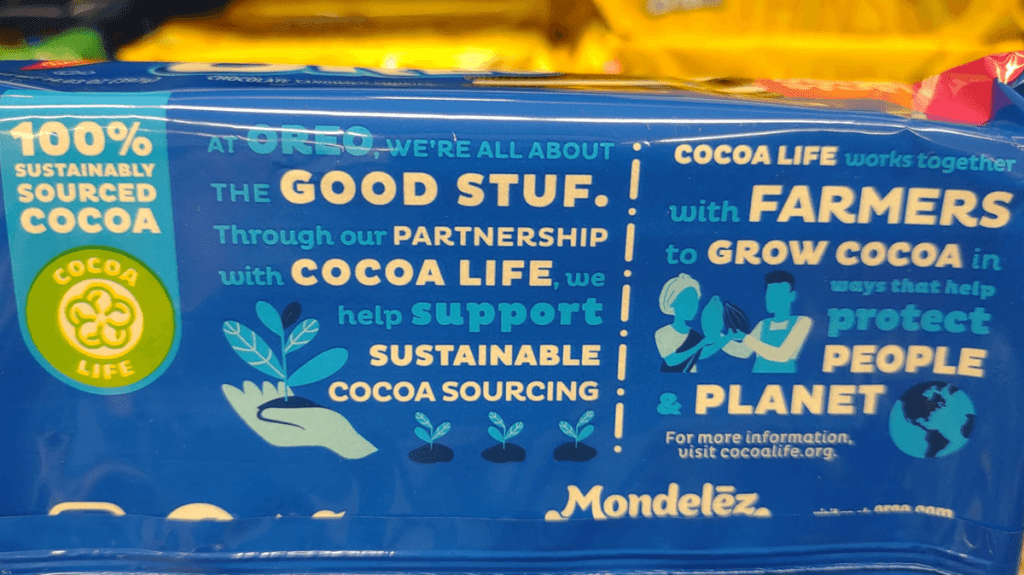

Many large food corporations tout in-house programs for ethical ingredient sourcing, usually represented by a catchy name and a logo. These are most common for products with large social and environmental impacts that are sourced from the Global South, such as coffee and chocolate. Examples include Nespresso’s AAA Sustainable Quality program, Hershey’s Cocoa For Good, Nestlé’s Cocoa Plan, and Mondelez’s Cocoa Life. Several now display logos on product packaging to persuade consumers that their products are ethical.

When it comes to these in-house logos, should we trust, avoid, or ignore them when aiming to make a responsible purchase? To answer that, let’s take a look at the best way to make purchasing decisions, from an ethical perspective.

How to make ethical purchasing decisions

Some companies are almost unanimously recognized as leaders in social and environmental responsibility. But how does this recognition come about? It’s almost always built on a foundation of products that speak for themselves, ethically, reinforced by third-party certifications and broader corporate social responsibility.

This is usually the order in which I’ll narrow down my selection process to make a purchase decision. In other words, I’ll first look for a product made of materials (and packaging) that are inherently more responsible – e.g., plant-based, renewable materials. Then I’ll look for a third-party certification that provides some assurance on the social and/or environmental impact. Finally, I’ll look at corporate responsibility of the brand(s) that I’m considering – renewable energy use, waste minimization, social equality, etc.

We shouldn’t underestimate that first step – considering the product from a very broad perspective – because it’s usually the most important one. Legumes are far better than beef, second-hand clothing is preferable to new clothing, and wood is generally better than steel or plastic. In other words, make your purchase decisions by starting with a fairly rudimentary comparison of the materials involved. Looking at the example of legumes vs beef, the land and carbon footprints of pea protein are 50 to 100 times smaller than the respective footprints of beef protein. That kind of difference makes the comparison no-contest, without even taking into account other factors (which also favor the legume anyway) such as animal welfare, water use, and the social impact of slaughterhouse work.

Let’s take another example: you want to buy a chopping board for the kitchen. In this case, we can confidently say that wood, a renewable material, is usually a better choice than plastic, a material that’s made from fossil fuels. This is pretty simple logic but it’s important to look at situations from this elementary perspective before getting into any exceptions or caveats. Wood is made of carbon that’s captured from the atmosphere: carbon dioxide gas (the main driver of climate change) is converted into solid wood via the magic of photosynthesis.

The next step is to choose between similar options, such as a selection of wooden chopping boards, recognizing that they are not all equal. This can be done by looking a little deeper into the material, perhaps deciding that bamboo is a good option, as long as it’s responsibly sourced. This is also where third-party certifications are a useful tool – we can check if the chopping board is certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), for example.

In cases where we want to buy product that’s ethically-sensitive, such as coffee or chocolate, we tend to rely more on third-party certifications and other information on corporate responsibility. By ethically-sensitive, I mean that the social and environmental impacts range widely: from slavery, child labor, and deforestation at one extreme, to bringing people out of poverty and maintaining biodiversity at the other.

Pretty much every third-party certification has received some criticism, and that’s the way it should be. Academic groups and NGOs frequently examine the efficacy of programs such as fair trade certification, suggesting improvements and helping to keep them accountable. I’ve covered some third-party certifications in previous posts (e.g., coffee certifications and sustainable seafood) but do plan to examine peer-reviewed studies on their efficacy in a future post. For now I’ll say that I tend to look for a good environmental certification (e.g., organic, bird-friendly, or regenerative organic certified) and a social impact certification (e.g., Fairtrade).

But what about those in-house programs, like Mondelez’s Cocoa Life, that are often promoted as logos on packaging?

Are in-house ethical sourcing programs to be trusted?

When I see a program such as Mondelez’s Cocoa Life, Nestlé’s Cocoa Plan or Hershey’s Cocoa For Good, I view them the same as I would any part of a corporate trade policy or social responsibility plan. It can be helpful to have policies mapped out in a document, although sometimes instead of firm policies we get a brochure documenting stories that are hard to put into perspective or judge in terms of efficacy. Of course, some of these programs seem better than others in terms of commitment made, but who knows which are better in terms of execution?

Coupled with that, most of these companies have historically performed poorly on ethical fronts – particularly when it comes to sourcing of sensitive commodities such as coffee and cocoa. They have constantly moved the goalposts on dealing with issues such as deforestation and slavery in the chocolate industry. Are we naïve to put any faith in their new programs? Is this a case of fool me one, shame on you; food me twice (or in this case, half a dozen times) shame on me?

One thing is for sure: displaying these in-house logos on packaging is deceptive simply because they can easily be mistaken for third-party certifications.

Many consumers probably don’t fully realize that these are not the same as third-party certifications and, for the rest of us, probably a small corner of our mind starts to believe in them. Or, perhaps more exact, if we have concerns about the company but don’t have time to dally (and we just want peanut butter cups) then the logo allows us to silence those concerns enough that we can get on with our day. This is modern marketing and public relations – just make consumers doubt their concerns enough that they won’t boycott you.

We need third-party certifications

Another way of describing why we should avoid in-house ethical logos is to look at why we specifically need third-party certifications. A lack of trust in the actions of large corporations, coupled with diminishing government control over them, is the primary reason that we increasingly look towards independent certifications for assurance on ethics. Third-party certifications have non-corporate coordinating bodies, typically NGOs, which set standards and monitor compliance. Laura Raynolds, Professor of Sociology at Colorado State University and Director of the Center for Fair & Alternative Trade put it as follows:

Over recent decades globalization has fueled the spread of neo-liberal policies around the world, undermining government regulations in national and international arenas. Deregulation in agro-food sectors – a traditional bastion of government control – has been particularly dramatic.”

Of course, there are also many companies and products worthy of support that have no certifications, such as those mentioned in the top 10 ethical chocolate brands and this post on direct trade coffee. But when it comes to those brands from large multinationals that only offer a logo denoting an in-house ethical sourcing program, I would say avoid.

Thanks for reading! If you are interested in ethical consumption, climate change, food sustainability, plant-based food, etc., consider visiting my other blog, Ethical Bargains, which evaluates products for social and environmental impact. In the most recent post on Ethical Bargains, I examine Hu Kitchen, a chocolate maker that was recently acquired by Mondelez.

Discover more from The Green Stars Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you. This was so informative , yet simple to put into active consumer choice practices.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Cecelia!

Much appreciated.

LikeLike

I don’t trust self-certifying corporations. After all, it’s the same Nestle that killed infants in Mexico in the 80s with their contaminated formula and didn’t even seem to care.

LikeLike