Here’s the third post looking at the evidence that neonics are harmful to bees. I’m a research scientist and have no agenda here, other than uncovering the truth. In parts one and two I’ve focused on the toxicity of the best-selling insecticide, imidacloprid, to honey bees. But nature is complex, particularly systems like a bee colony that work together as a collective, dependent on nectar and pollen foraged from within a few miles. Their abilities to navigate, learn, communicate, reproduce, and resist infections all depend on their health – and, like anyone, their health depends a good deal on the food they eat.

Communication: the honey bee dance.

If you’ve never seen the honey bee dance, take a look at the short video below. In 2014 UK scientists published a paper showing how the dance points the way to flowers. The angle of the dance indicates direction (relative to the sun) and the length of time that the bee waggles its abdomen indicates distance. Together these dance moves point other bees to a specific spot for foraging.

Here are a few findings from science papers that consider broader issues:

Subtle effects of neonics

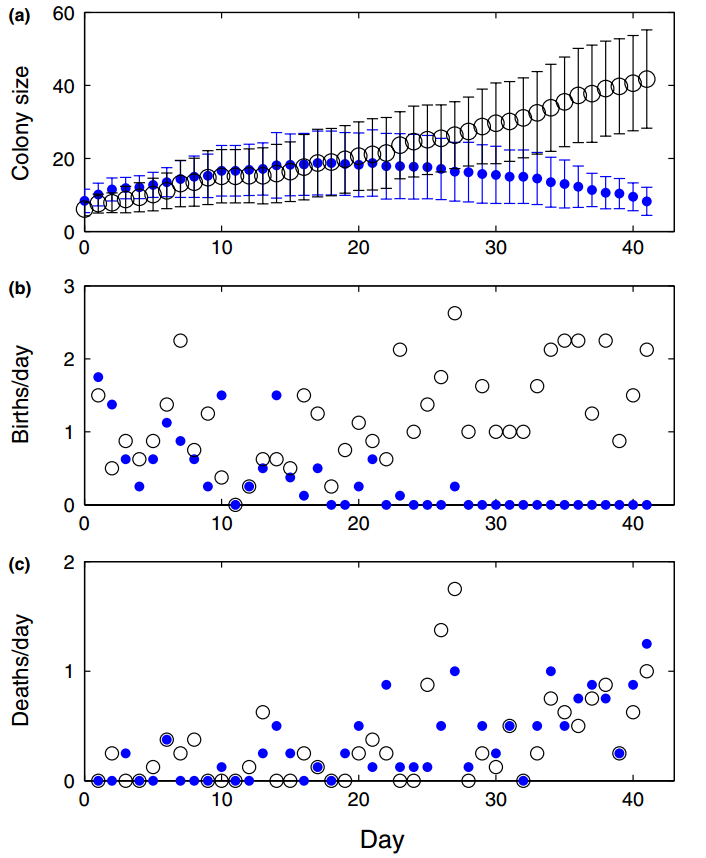

A 2013 paper from UK scientists, Chronic sublethal stress causes bee colony failure, describes their mathematical model for bee colony population dynamics. A key idea, also popping up in other papers, is the Allee effect (named in the 1930s after the ecologist Warder Allee) – the idea that a collective’s survival depends on maintaining a minimum population. For example, meerkats depend on cooperative defense (vigilance), so smaller collectives are more vulnerable. In the case of bees, there are many cooperative aspects (feeding being an important one) so it’s easy to see how a bee colony can collapse if the population drops below a critical level. The researchers tested their model by feeding bees with 10 µg/kg imidacloprid and found that the pattern of population decline matched their model.

“They have many workers and are able to buffer some effects of stress. However, if too many bees become behaviourally impaired, irrespective of the reason, the colony reaches a tipping point and is set on a path to failure through moderate, but chronic, levels of stress. There is, consequently, a critical stress level, where a small change in the amount of stress can mean the difference between colony growth or failure.”

You can see from the figure above that the population suffered more from lack of births than from increased deaths.

Tying in with this, a 2016 paper from US Dept. of Agriculture (USDA) scientists showed a 50% reduction in bee sperm viability following exposure to imidacloprid (20 µg/kg).

Bumble bees may be even more sensitive to neonics

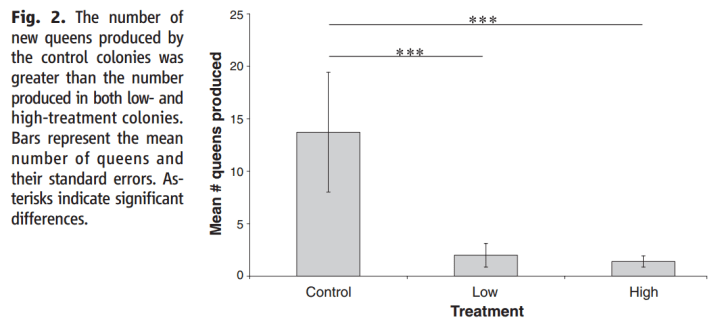

UK researchers reported in a 2012 Science paper that Bombus terrestris (the most common European species of bumble bee) experienced an 85% reduction in queen production over the season when fed for two weeks with pollen spiked with only 6 µg/kg imidacloprid and then allowed to forage independently.

Other insecticides also affect honey bees

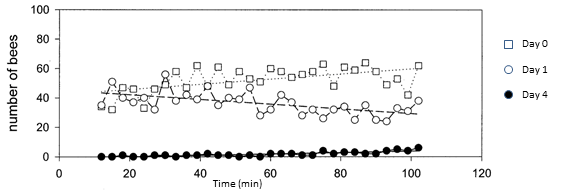

A 2004 paper, A Method to Quantify and Analyze the Foraging Activity of Honey Bees, describes how researchers used video to monitor and quantify bee foraging at various feeding stations containing syrup. Feeding on syrup that was spiked with Imidacloprid (6 µg/kg) induced a decrease in the proportion of active bees. The effect was even more pronounced when syrup was spiked with another insecticide, fipronil, at 2 µg/kg.

Fipronil is a different class of insecticide but, like neonics, also targets insect central nervous systems. BASF sell fipronil-coated corn and potatoes and although the US EPA banned fipronil for use on corn in 2009, BASF say that they can legally sell it until their supplies run out – and so they are.

Fungicides may also affect bee health

The authors of this 2014 paper studied apiaries across Belgium and tested for the presence of various viruses, fungicides, insecticides and herbicides to see if any of them correlated with honey bee colony disorders.

“A significant correlation was found between the presence of fungicide residues and honeybee colony disorders.”

“Interestingly, one metabolite of (the fungicide) boscalid, 2-chloronicotinic acid, is similar to the 6-chloronicotinic acid, a metabolite of imidacloprid.”

On the subject of fungicides, other researchers discovered a practice by bees of “entombing” pollen to lock it away. The entombed pollen contained high levels of the fungicide chlorothalonil and the practice of entombing pollen was associated with increased colony mortality.

The Problem: Industrial Agriculture

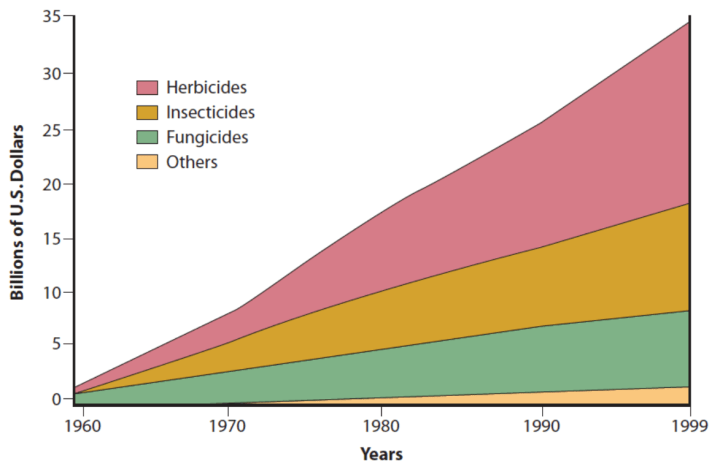

There are many other papers – I had to do a lot of weeding and editing here. I mentioned in a previous post that a new type of additive added to many pesticides (to increase penetration into the plant) is suspected to cause olfactory learning impairment (i.e., bees can’t use their sense of smell so well for foraging). When it comes down to it, I don’t think the problem boils down to only neoinics, or is restricted to only honey bees. Pesticide use has increased a lot since 1960, as you can see on the chart below. For more recent data, the US Geological Survey (USGS) has charts and maps showing how much the usage of pesticides such as imidacloprid has increased since 2000 (about 10-fold, not including coated seeds).

A recent UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) report calls for end to industrial agriculture.

In the words of the Director-General of FAO, we have reached a turning point in agriculture. Today’s dominant agricultural model is highly problematic, not only because of damage inflicted by pesticides, but also their effects on climate change, loss of biodiversity and inability to ensure food sovereignty.

When it comes down to it, industrial agriculture is approaching a level where the land is sterilized. Broad-range pesticides are used liberally, impacting species far beyond those that may pose a threat. Insects that control pests are also wiped out. The kicker being that the more ecosystems become out of balance, the more industrial agriculture actually depends on these products. It’s a negative spiral that we need to break out of immediately.

A final word from two entomologists

If you have a few minutes, take a look at this story from the Washington Post about two USDA scientists who appear to have been punished for speaking out against neonics. I’ll summarize the gist of it.

Dr. Jonathan Lundgren “ran his own lab and staff for 11 years, wrote a well-regarded book on predator insects, and published nearly 100 scientific papers” until his career at the USDA began to take a downturn.

He believes the problem began in 2012, when he published findings in the Journal of Pest Science suggesting that a popular class of pesticides called neonicotinoids don’t improve soybean yields.

The article also features Jeffrey Pettis, who served as Principal Investigator on many bee studies including the sperm viability research mentioned above and the 2015 paper that dominated my last post. The Washington Post article suggests that Pettis was demoted after suggesting that neonics were a problem while testifying in front of congress.

My guess is that Dr. Pettis was overruled when it came to writing the conclusion to the paper I discussed in the last post. So I’ll leave the final words to Lundgren and Pettis (Source: Washington Post):

“I have seen more direct evidence that Congress was influenced by industry than I ever felt with regard to the USDA.” Dr. Jeffrey Pettis.

“Pesticides, herbicides, fungicides should be something we resort to, not a first option.” Dr. Jonathan Lundgren.

“What we have is a biodiversity problem.” Dr. Jonathan Lundgren.

What you can do to protect bees

Choose food that’s sustainably grown – organic, pesticide-free, or from a farm that uses integrated pest management. Here’s a review of a winery and farm that plants specific cover crops to attract beneficial insects.

If you use honey, choose organic or buy from local beekeepers who practice sustainable beekeeping. Industrial beekeepers often remove all of the honey from the hive and provide syrup for the bees. According to this paper:

The widespread apicultural use of honey substitutes, including high-fructose corn syrup, may thus compromise the ability of honey bees to cope with pesticides and pathogens and contribute to colony losses.

Plant wildflowers. Here are some guidelines for creating a bee garden from The Honey Bee Conservancy.

Make sure seeds that you buy are not coated with neonics! Many garden centers and home supply stores stocked seeds that are actually coated with neonics. There’s an increasing awareness about this now and some stores have ditched neonic-coated seeds.

Join campaigns and check out the Pesticide Action Network and this Bee Action page from Friends of the Earth (FOE).

If you ever need to buy pesticides for your garden check out a guide to safer options such as the list at the end of this pdf from FOE.

If you frequent an area with managed land (school, university, park, golf course, etc.) encourage the owners to avoid neonics and use integrated pest management. Pass on the Municipal Purchaser’s Guide to Protecting Pollinators from FOE.

Also, see this update post on the EU formally instating a neonics ban in 2018 while the US continues to use the insecticides liberally. Action is most needed in the US.

Thanks for reading! Please share these bee posts if you get a chance.

Next week I’ll cover something a little lighter – and shorter 🙂

You post came at the right time! It couldn’t be anytime better. Someone at my end, just ask this question. Please see my post “What I learn today – May 15, 2017”. I have shared this post at my end. So that he and others can read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha – thank you! There really is a lot of confusion about the issue and some of the media coverage is not helping. So, thanks a lot for taking the time to share it 🙂

LikeLike

commendably researched & expressed!

i’ll gladly share it with others 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, on behalf of the bees and other pollinators 🙂

LikeLike

I hope for positive change. I taught organic horticulture here in Ireland in local schools until last year and people are definitely getting more mindful of these issues.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Have you read this ?

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.3896/IBRA.1.53.5.08

It seems that only in a laboratory do bees ever receive a harmful dose. Even when placed in the middle of neonic coated monoculture with no other available forage, neither bumblebees nor honeybees suffered.

No conspiracy theory, just the opinion of the 2 top scientists in apiculture in the UK, that when it comes to identifying the threats to pollinators, neonics was a dead end.

Tbey (and me) are in complete agreement with you on the subject of habitat loss though.

LikeLike

Hi Stuart,

Thanks for your comment and for sharing the article. I’ve looked into it and here are my thoughts.

The article that you shared is a review (i.e., it contains no original research but provides a summary of research that others have done).

The authors of the review have published several reviews or opinion pieces all closely mirroring the Bayer/Syngenta stance on the issue.

The research mentioned in the review that you refer to (“..placed in the middle of neonic coated monoculture with no other available forage..”) comes from Thompson et al. (2013). The Thompson et al., document is actually a report rather than a peer-reviewed paper. Have you read it? Here it is.

The authors state that “This study was not a formal statistical test of the hypothesis that neonicotinoid insecticides reduce the health of bumble bee colonies.”

It should be noted that the study was conducted by DEFRA (UK Dept for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs) under Owen Patterson, who at that time was engaged in chummy correspondence with Syngenta in which he expressed his disappointment with the EU ban.

Even considering all of these red flags, it’s worth taking a look at the data in the DEFRA report.

For example, Figure 3 shows that that bumble bee colonies exposed to imidacloprid-treated crops (oilseed rape, site C in the paper) grew to less than half the weight of control colonies.

Also, Figure 5 shows that queen production in bumble bees in site C was half that of the control bees (site A).

So here’s my take on it:

1. The conclusions by the DEFRA group (Thompson et al.) don’t match their actual data (similar to the USDA paper I discussed in part 2).

2. The authors of the review that you shared are setting the bar low by citing Govt. reports rather than peer-reviewed science papers.

3. On top of that, their conclusion:

“A study of free-foraging bumble bee colonies in the UK (Thompson et al., 2013) failed to detect the reduced queen production found in laboratory based studies (Whitehorn et al., 2012) even though the colonies all foraged on treated oilseed rape,” is directly at odds with the data that they are quoting (Figure 5 in Thompson et al.).

It looks like they either didn’t actually read the full Thompson report and took their executive summary conclusions at face value without checking them. Or they knowingly ignored the data and quoted the erroneous conclusion by Thompson because it fit with their agenda.

In any case it’s a good lesson in fully investigating the data behind any claim.

If anything, the DEFRA report (despite their misleading summary) supports the hypothesis that imidacloprid is harmful to bumble bees in realistic field situations.

Please feel free to discuss further after you have a look a the DEFRA report.

Cheers!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m going to have to come back and read all these posts later. It’s clear that you’ve done a great deal of research. Why must industrial agricultural role the dice with all out futures, eh?!😩

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. Yeah, they are a bit long. I tried to be as thorough as possible and then edit it down as much as possible but they still ended up being pretty long. Unavoidable, I suppose, to cover the topic properly. If you have limited time (and don’t need convincing) then you could skip to the last part of this post – What you can do. Thanks for getting in touch!

LikeLike

Do you know if there has been any research done to the effect of neonics on other animals besides bees?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Mira!

Hope you are doing well. I just posted a new article about the impact of the neonic pesticide imidacloprid on many species, from insects and crustaceans to trout and birds.

https://greenstarsproject.org/2021/03/31/risk-benefit-analysis-bayer-imidacloprid-admire-sds-toxicity/

Note that the UK almost said yes to using neonics again, last month 😦

J

LikeLike

Q from Gloria: Good and eye-opening article. Thank you! Do you know if Seresto collars for pets are a problem (negatively affect bees)?

Hi Gloria,

Thanks for the comment. Well, the Seresto collars are definitely an issue for some pets. The bees are most impacted by pesticides in their food (pollen, nectar), so the most important thing is to avoid imidacloprid, which is the main active ingredient in the collars. Support pesticide-free farming and avoid imidacloprid in gardening products.

LikeLike