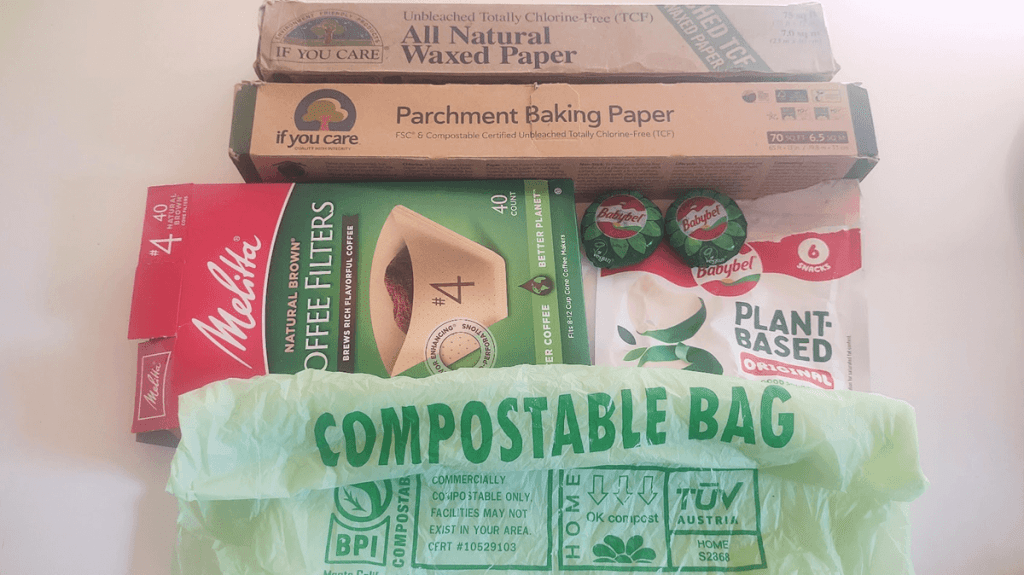

I’ve been looking at the efficacy of various third-party certifications lately and have covered most of the big ones – fair trade, FSC, B Corp, etc.). I’ll wrap this series up for now by examining certifications for compostable plastics (biodegradable bags, packaging, cups, utensils, etc.).

The two most common compostable materials are polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), which are produced by various bacteria, and polylactic acid (PLA), a polymer of lactic acid, which can also be made by microbes.

So the major compostable plastics can be produced, in part at least, by microbes fed with plant-based nutrients (sugars, starch, etc.). At the end of their life, these materials can be broken down again by microbes in compost facilities. They are clearly better than conventional, petrochemical-based plastics in terms of green design principles but how about in practice, when everything is factored in?

So, before we get to certifications, let’s start by addressing common criticisms of compostable plastics.

Criticism of compostable materials

Quite a few of the high-profile articles criticizing compostables are written by folk in the business of reusable containers. Yes of course we should choose reusable items whenever possible – a personal coffee mug, utensils for a party, etc. But the correct way to evaluate the environmental impact of compostable plastic is by comparison to conventional plastic.

Most of the critiques of compostables (such as this one from the Natural Resources Council of Maine) raise similar points, which I’ll address forthwith!

1. Compostable products contribute to confusion. There has been perpetual confusion, dating back way before compostables, over what goes where when it comes to our domestic waste streams. I feel confused sometimes too but this is where a certification comes in – a logo that makes it clear that your item does belong in the compost. Just because something is confusing at the moment, it doesn’t mean that it’s not worth persevering with.

2. Some molded fiber compostables contain toxic PFAS. There are bad examples in almost every situation but we shouldn’t let them define our opinion. The trusted certification programs for compostables (see below) have a list of disallowed chemicals, including PFAS, the fluorinated hydrocarbons nicknamed forever chemicals.

3. Disposable compostables still pollute our forests, waters, and ocean as litter. Like the first point, this is more of an educational issue – compostable items are not meant to be tossed away into forests or rivers! There’s also no evidence that this is happening any more than with conventional plastics.

4. Compostable disposables distract from what really needs to happen. And that’s switching to reusable cups, utensils, etc. No argument here that we should use reusable items, as much as possible. But there’s an increasing amount of freshly-made petrochemical-based plastic put into use every year, and it can’t all be replaced by reusable items.

So the real question is: do compostables make sense as a replacement for petroleum-based plastics? I’ll address that question in part 2 of this post but, spoiler alert, the science suggests that they do make sense. Further improvement is expected but many compostables already have significantly lower environmental footprints than conventional plastics.

Addressing most of these criticisms comes down to two things: use reusable items whenever possible and, when you buy a compostable item, make sure it’s third-party certified. Certification ensures that it’s PFAS-free, suitable for composting and clearly marked as such. And yes, don’t throw your compostable utensils in the ditch after your picnic!

What are oxo-biodegradable plastics?

Looking at peer-reviewed science pubs, a 2022 paper titled, Key issues for bio-based, biodegradable and compostable plastics governance, brings up similar points but also adds a warning that “oxo-biodegradable” plastics are not compostable and also generally not a good idea:

A recent example of materials claiming environmental benefits not delivered to consumers are the oxo-biodegradable polymers, formulated by the mix of pro-oxidizing agents with polyethylene or polypropylene which accelerate the initial fragmentation of plastic artifacts. Nevertheless, scientific evidence indicates incomplete degradation of these utensils after initial fragmentation. Furthermore, it has been suggested that oxo-biodegradable products may originate microplastics and therefore be more deleterious than conventional plastics. Hence, they were banned from Europe by the European Commission (EU, 2018).

The best way to avoid faux-biodegradable products like these oxo-biodegradable plastics is to seek out products that are certified to degrade when composted.

Third-party certifications for compostable items

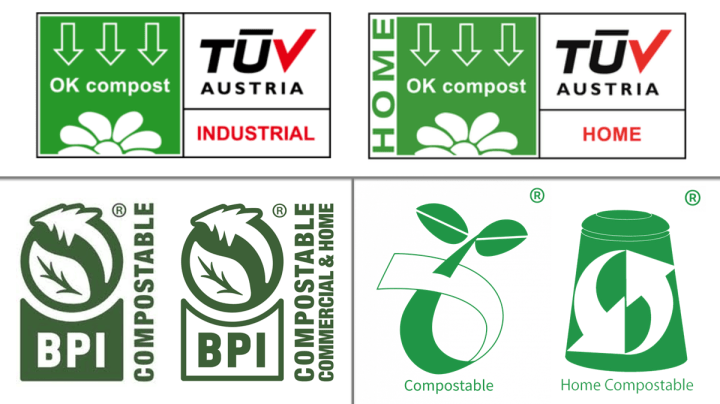

The biggest certification bodies for compostable items are the US-based Biodegradable Products Institute (BPI), the Austrian certifier, TÜV, and the Australasian Bioplastics Association (ABA). These bodies certify that the materials pass tests designed to measure biodegradability (as defined by a standards body such as ASTM). In addition, all three of them also verify that the certified material is PFAS-free by testing for fluorine content.

BPI used to only certify items for industrial composting but, in Sept 2025, launched a certification for items that are compostable both in commercial facilities and at home.

To earn the new certification, products must break down completely in the lower temperatures of backyard composting environments in addition to meeting existing certification criteria.

TÜV is the most extensive certifier, including categories for materials to be used in marine or soil environments. But for most consumers the two main options are certification for composting in an industrial facility or in a home compost pile. If an item is certified for home composting then it can also be composted in an industrial facility (i.e., dropped into your green waste bin for collection).

Here’s some general info on compostable materials from the ABA:

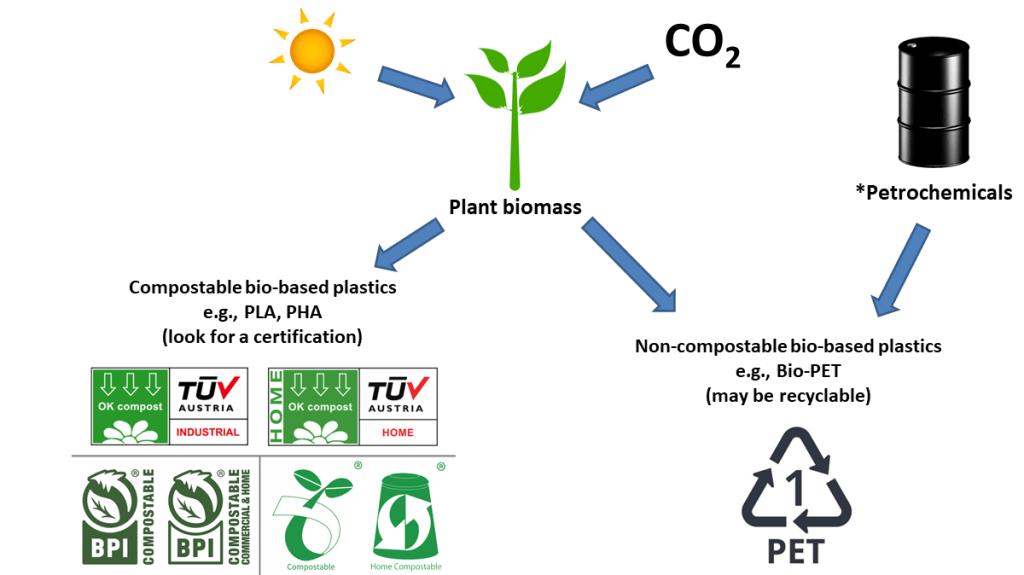

Compostable versus bio-based plastics

Some of the terms used to categorize plastics can be confusing, especially to consumers trying to figure out where to dispose of something – recycling, compost, or trash. Thankfully, oxo-biodegradable plastics are largely phased out, but there’s still another term to consider: bio-based.

The term bio-based (or biobased) refers to any kind of material that’s made from renewable feedstocks such as plant-derived sugars. Bio-based plastics can either be compostable (like PLA and PHA) or non-compostable, such as bio-PET (polyethylene terephthalate).

Most non-compostable bio-based plastics (e.g., Bio-PET) are chemically identical to their petrochemical-based counterparts (e.g., PET) but just made from plant-based sugars (or a mix of sugars and petrochemicals). Some of them have merit, particularly if we manage to make some long-awaited improvements in plastics recycling. The most common example is bio-PET but there are also others such as the polyamide used in some ON running shoes.

Bottom line: when confused by these terms, the best way to know if something is compostable is to look for a certification logo from a third party such as TÜV, BPI, or ABA.

In the next post I’ll examine the environmental impact of compostable plastics versus conventional plastics.

Discover more from The Green Stars Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.