I wasn’t aware that social media influencers were vehemently warning about seed oils until I came across a few people talking about them in real life. A customer who walked into a local café was at first interested in a vegan milk option but then, looking at the ingredients, rejected it. Oh no, it’s made with seed oils! She exclaimed, and distanced herself from the product as if it were radioactive. (The seed oils in question were sunflower and safflower.)

Some concerns with seed oils (GMO crops, hexane extraction) aren’t specific to seed oils and, more importantly, are easily avoided simply by choosing organic. Articles like this one helped put the hexane extraction in perspective for me (our intake of hexane from gasoline fumes is way higher) but I still prefer organic cooking oils for reasons that I’ll get into later.

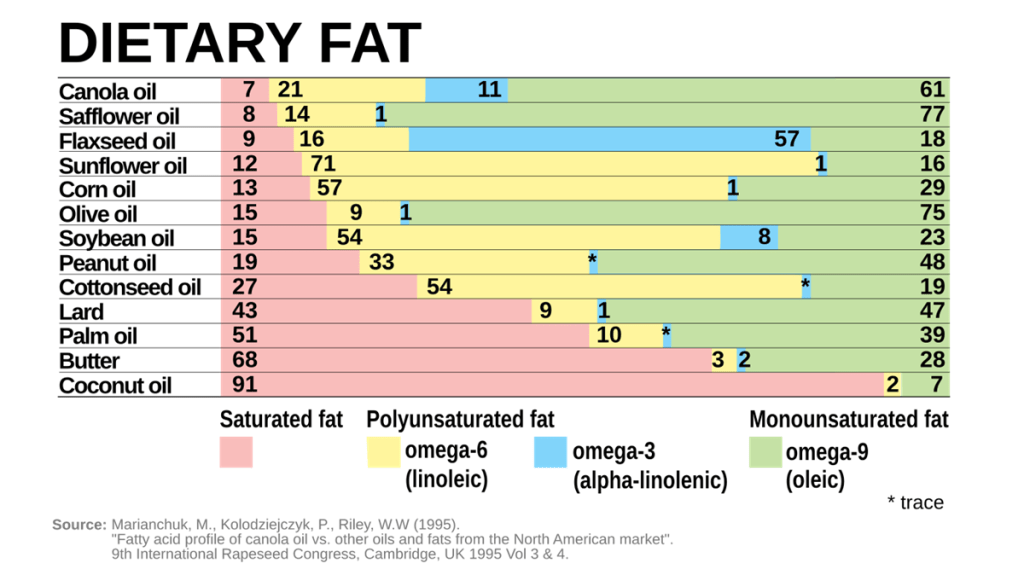

Most of the other concerns with seed oils are focused on the omega-6 fats that are abundant in many, but not all, seeds and nuts. There are many articles from field experts and scientists who have taken the time to go through the literature on the topic (this is a good one) so I won’t cover it at length here. Long story short: consuming omega-6 fats is preferable to a high intake of saturated fats.

However, there’s one remaining issue that’s valid and worth discussing: the ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fats in our diet. Some seed oils are very high in omega-6 fats and contain little omega-3 fats, but there are exceptions: notably rapeseed oil, also known as canola oil.

Why not just stick with olive oil?

It’s widely agreed that olive oil is one of the healthiest cooking oils but it’s expensive, has a high water footprint and is very low in omega-3 fats. So, after a bunch of research, I’ve come to the conclusion that a blend of canola and olive oils may be one of the best options, all-round.

Why a canola/olive oil blend is actually a good choice

Whenever I’m shopping for vegetable oil, blends are usually in my blind spot. I generally didn’t even consider them. A major reason for this is that when I see a bottle of an olive /canola oil blend (for example) it would make me mad. Not so mad that I’m ranting to myself and stomping my feet in the middle of the supermarket, but just a little annoyed. Because, very often, the packaging looks like it’s designed to make customers-in-a-hurry mistake it for pure olive oil.

My opinion has changed on blends – actually to the point where I now think a canola /olive oil blend* may be a great idea, overall. There are three main reasons for this: value, health, and sustainability.

*I’ll probably make my own blend, rather than buying them pre-blended, as it’s easier to find good oils in pure form.

Canola/olive oil blend from a value perspective

I’ll keep this short: canola oil is considerably cheaper than olive oil so a blend will be a lot cheaper than buying pure olive oil. Canola oil has a neutral taste so a blend will pretty much taste like the olive oil component. Sure, it’ll be a little weaker, but when I use a blend for cooking (e.g., pan-frying asparagus or potato) I don’t perceive a difference in flavor. Overall it seems that an oil blend can be a good budget-friendly approach to take as the price of olive oil increases.

Canola/olive oil blend: health perspective

This could turn into a PhD thesis, so I’m going to make an effort to be brief 😉

First off, let’s talk about the “perils of seed oils” and an optimum mix of omega-3 and omega-6 fats.

An optimum fat balance

Much as I scoff at alarmist reactions to seed oil, I have also wondered about them and spent a lot of time researching an optimal balance of fats in our diet. My opinions on this topic are in tune with the scientific consensus. Here’s a quick summary:

- We should minimize our intake of saturated fats, especially the long-chain saturated fats found in animal products and palm oil (strong scientific consensus). The medium-chain saturated fats found in coconut oil appear to be healthier than the long-chain fats because of the way they are metabolized.

- It’s healthier to consume unsaturated fats, present in most plant and fish oils, than long-chain saturated fats (strong scientific consensus). Within these unsaturated fats it’s useful to examine our intake of the three groups: omega-3, omega-6, and omega-9 fats.

- The omega-9 fats (monounsaturated fat) are considered to be good for health, lowering bad cholesterol and blood pressure. The most abundant omega-9 fat in our diets by far is oleic acid – it’s the main component in olive oil but also high in canola oil and even in sunflower or safflower oils that are labeled high-oleic.

- Then, the contentious issue is that the omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids compete with each other in our bodies. Both are required, but people are much more likely to have a shortage of omega-3 fats than omega-6 fats. So for most of us, we should aim to increase our omega-3 fat intake as it’s likely to be low.

Some seed oils (corn, soybean) are high in omega-6 fats while high-oleic varieties of sunflower and safflower oil are enriched in omega-9 fats and therefore omega-6 fats are reduced to moderate levels. Canola oil is high in omega-9 fats and also fairly high in omega-3 fats (alpha-linoleic acid, ALA), balancing the moderate omega-6 fat content.

Consider the typical fat content for olive and canola oils shown in the image above.

Olive oil has an omega-3, 6, and 9 fat content of around 1%, 9%, and 75%, respectively: not much omega-3 and quite a bit more omega-6, in comparison.

Canola oil has an omega-3, 6, and 9 fat content of around 11%, 21%, and 61%, respectively: pretty well balanced with almost half as much omega-3 as omega-6 fat.

So while both oils are fairly high in healthy omega-9 fat (oleic acid), canola has quite a bit more omega-3 (ALA) than olive oil. If you make a mix of 80% canola, 20% olive oil then the final content would look like:

Canola/olive oil blend (80/20): Omega-3, 6, and 9 content of 9%, 19%, and 64%, respectively. Still very high in healthy omega-9 fats, of course, and the ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fat is an almost ideal 2:1.

Omega-3 fat sources for vegans and vegetarians.

Having a balanced intake of omega-3 and omega-6 fats may be especially important for vegans, vegetarians, or anyone who doesn’t eat fish. Even then, conversion of the omega-3 fat ALA into the longer omega-3 fats (EPA and DHA) is not very efficient. The exact efficiency of this conversion varies, so to be cautious I’d recommend that vegans take an omega-3 supplement (algal oil) from time to time. Vegetarians could seek out humane omega-3 enriched eggs (hens are provided with ALA-rich feed such as flaxseed and convert this to EPA and DHA).

Canola/olive oil blend: sustainability perspective

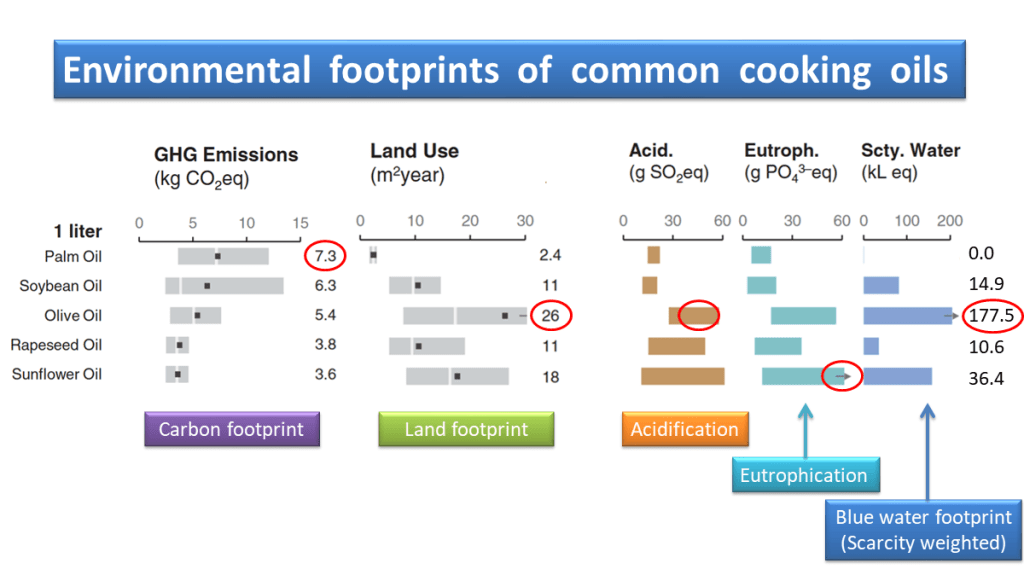

The image below shows data on the environmental footprints of five major oils. I circled the oil with the largest footprint in each of five categories – and you can see that olive oil has the largest footprint in three categories – land use, acidification, and blue water (irrigation).

In most cases these differences are not huge, especially compared to the environmental footprints of animal products. However, the blue water footprint of olive oil is considerably higher than any other oil, especially when local water scarcity is factored in. And with climate change exacerbating water shortages in olive oil growing regions (Mediterranean, California) it would be good if we didn’t go crazy with olive oil.

The obvious oil with which to cut our olive oil from a sustainability perspective is canola (aka rapeseed), which doesn’t have any red flags in terms of environmental footprint.

There are a few important things to look out for besides these footprints, which I’ll quickly list before we wrap up:

- Most soy and sunflower grown in the US starts from neonic-coated seeds. Neonics, a class of pesticide, are a major factor in the decline in bee population so I seek our organic oils when possible to avoid them.

- The impact of palm oil goes beyond the environmental footprints listed above as it’s usually grown in rainforest ecosystems and has a high impact on these sensitive habitats (e.g., orangutans in Indonesia and Malaysia).

- Most canola crops grown in North America are treated with glyphosate, so you can seek out non-GMO or organic oil to avoid this (same goes for corn and soy).

Overall, canola (rapeseed) oil is a good choice from an environmental standpoint, with most downsides avoided by choosing organic.

From the three perspectives of value, health, and sustainability, I think a blend of canola (rapeseed) oil and olive oil is a good option. Another reason for using a blend of two oils for cooking is to introduce more variety into our diets – the spice of life! Try mixing a little at home to see how it works out for you.

Discover more from The Green Stars Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

James, it’s difficult keeping up with what is best for our health. I used to use canola oil before learning that olive oil was healthier.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It can be tricky for sure, Rose. Olive oil is a good choice but mixing with canola doesn’t compromise on heath and makes it easier on the planet and your budget 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the info. I’m going to look for canola/olive oil blend. I hope that at least one of the markets I shop at carries it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Or just buy some pure organic canola oil and then mix it in with your olive oil at home 🙂

Cheers!

LikeLike

Hi James, thanks for this post, it’s very good. One question: once you’ve made your blended oil, do you store it in the refrigerator or a cool dark place like cupboard or pantry? I always keep our (organic) canola oil in the fridge, and the EVOO in a dark cupboard as it would go solid in the fridge. So which is right for a blend? Thanks,

Laurie

LikeLike

Hi Laurie,

Thanks for your comment and Happy New Year!

I would say that a cool, dark cupboard is fine for the blend.

The main factors that lead to oils going off are time, heat, oxygen, and light.

The time factor is important, so a good strategy is to buy quantities of EVOO that you’ll use in around six months after opening.

Storing in the fridge is important for perishable oils like walnut or sesame but, as you point out, is not practical for olive oil as it’ll solidify a bit. A 20:80 olive-canola blend may stay liquid in the fridge – I haven’t run that experiment yet 😉

But as long as you’re not exposing your oil to heat (like storing it right beside the stove top) I think you’ll be fine.

Cheers!

James

LikeLike