The conversation about ultra-processed food (UPF) has really taken off in the last few years and one aspect of it is deeply concerning. I’m talking about the fact that the discussion on UPF serves the purposes of the meat industry and has been successful in curbing sales of plant-based alternatives to meat and dairy. And that’s concerning because the future of the planet relies on us choosing plant-based foods more than any other single factor.

The original focus of the UPF discussion, which most scientists agree on, is that some highly-processed snack foods are calorie-dense but nutritionally-poor. In the last few years, however, research papers and media articles have become increasingly focused on plant-based alternatives to meat, which are now categorized as UPFs. “Focused on” is perhaps the wrong term, here, as most of these papers and articles lack hard evidence or any meaningful discussion on the health impact of plant-based meat. More insidiously, meat-alternatives are mentioned in passing, hinting at a health risk, which is often enough to sway the public.

In my last post I examined a recent, high-profile paper published in The Lancet that examined links between UPF and cardiovascular disease. The paper, which received a lot of media attention, claimed that “plant-based UPF” poses a health risk, several times implying that their study examines meat alternatives such as vegan burgers and sausages. However, the actual diet consumed by study participants mainly consisted of processed bread, cakes, biscuits, fries, pizza, confectionery, and soda. The language used in the paper was an egregious misrepresentation of the actual scientific content. Articles on the paper in major media outlets picked up on this language (and the language in the paper’s accompanying press release) and gave the impression that the researchers had actually found some evidence on the topic. They had not, but how many readers are going to check?

Then the kicker came when I noticed that the Lancet paper’s authors included Carlos Monteiro, who started the conversation on UPF in 2009. Prof. Monteiro and colleagues at the University of São Paulo introduced a food classification system, NOVA, which has since been adopted by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Administration (FAO). Here’s a quick summary of how UPF and the NOVA system came to dominate our conversation on food.

Origin of the NOVA classification system

For decades there has been much scientific interest in the health impact of processed food and a decent level of public awareness on issues with soda and fast food. But the idea of a classification system for UPFs is only a few years old.

Prof. Carlos Augusto Monteiro, a nutrition researcher at the University of São Paulo, sparked the current conversation on UPFs with a paper he published in 2009. It’s not a peer-reviewed paper but an “Invited Commentary,” which he titled: Nutrition and health. The issue is not food, nor nutrients, so much as processing. Monteiro gives a sense of taking on the establishment, citing soft drinks and biscuits made by giant multinationals as the enemies.

Ultra-processed products are typically branded, distributed internationally and globally, heavily advertised and marketed, and very profitable.

His conclusion is a bit heavy handed, however, stating that the “only rational approach” is to introduce “fiscal and other formal policies similar to those that make cigarettes and alcoholic drinks more expensive and less accessible.”

Way to spoil our fun – all we wanted was a biscuit to go with our cup of tea! But seriously, his message is understandable – we should eat less junk food and limit its availability in schools, etc. He certainly established the term “ultra-processed,” using it 19 times in his short commentary.

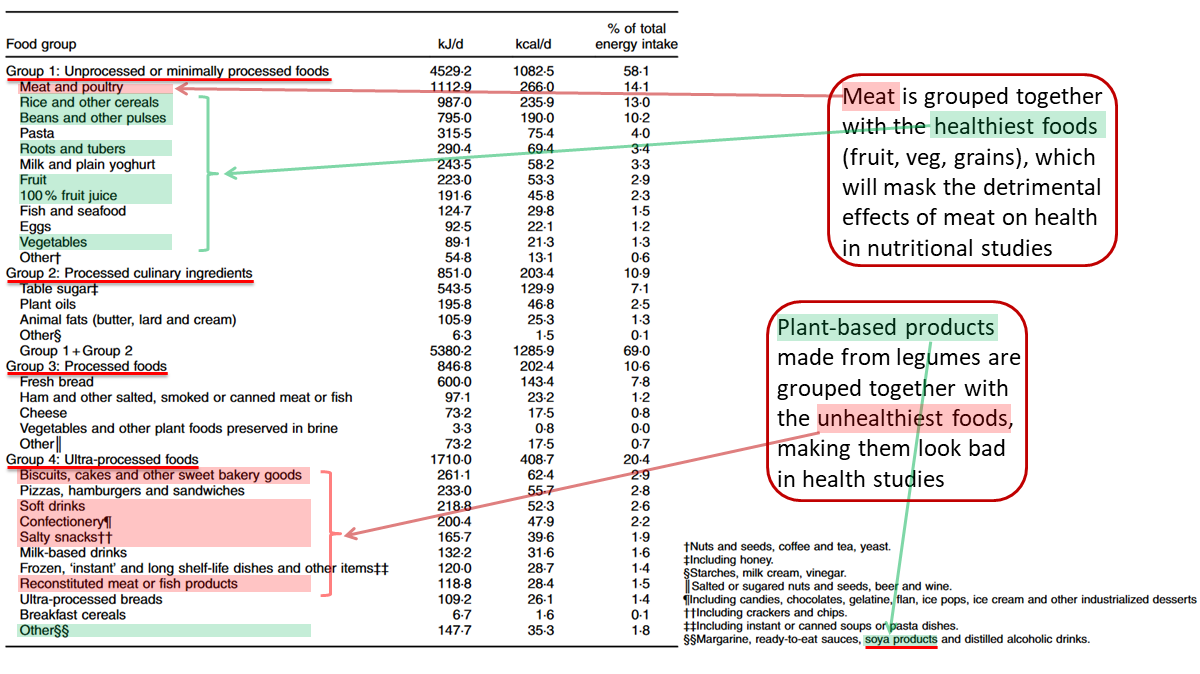

Building on this, Monteiro’s group, funded by the state of São Paulo and led by Monteiro’s PhD student Maria Laura da Costa Louzada (another co-author on the 2024 Lancet paper) published the “NOVA” food classification system in 2017. The NOVA system divides our food into four groups, with Group 1 comprising unprocessed foods that are good to eat and Group 4 comprising ultra-processed food (UPF) that we should avoid. This system has now been adopted by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Administration (FAO) as their preferred way to classify processed food. The table below shows how food is broken down into four groups and also highlights my major issue with this system (and the whole UPF topic).

Before getting into the meat issue, let’s look at some criticism of the NOVA system by other scientists

Criticism of the NOVA system

A study, published in 2022, asked the question, how functional is the NOVA system? The authors were concerned that:

Because its classification approach is purely descriptive in nature, it opens the door to ambiguity and differences in interpretation. Indeed, even experts face difficulties and have disagreements when employing it.

Their study showed that nutrition experts asked to categorize foods disagreed significantly on which foods belonged in the UPF category. The researchers concluded that their findings raise questions about the usefulness of NOVA and:

…on the reliability of conclusions from epidemiological studies that use NOVA as well as on NOVA’s ability to guide public health policy or provide useful information to consumers.

A debate on UPF took place between Carlos Monteiro and renowned Danish nutritionist, Arne Astrup, in the format of three papers. Astrup argued against the reliability of health studies on UPF because they are based on observational studies rather than randomized controlled trials. (The recent Lancet paper on UPF, discussed in my previous post, was based on an observational study that, in fact, was not designed to answer the questions asked by Monteiro and colleagues.)

Further, Astrup states that many of the observational studies on UPFs can be explained by simple factors such as energy density, fiber content, and added sugar. (Again, this looks to be the case in the Lancet paper.)

Clearly, many aspects of food processing can affect health outcomes, but conflating them into the notion of ultra-processing is unnecessary, because the main determinants of chronic disease risk are already captured by existing nutrient profiling systems.

In conclusion, the Nova classification adds little to existing nutrient profiling systems; characterizes several healthy, nutrient-dense foods as unhealthy; and is counterproductive to solve the major global food production challenges.

So what are we gaining by discussing the level of processing rather than fiber content, added sugar, etc.?

More critically, is the NOVA system and the UPF debate actually doing serious harm?

How the NOVA system favors the meat industry

In the debate on the NOVA system, Arne Astrup had argued that “UPFs also include foods generally considered healthy, such as vegan and most plant-based milk alternatives, as well as meat substitutes” and that “UPFs contribute ∼40% of total energy intake in vegetarian and vegan diets.”

In other words, the NOVA system takes the plant-based alternatives to meat and dairy and labels them as UPF and therefore BAD. Meanwhile, meat and milk are labeled as unprocessed and therefore labeled as GOOD.

It’s not just about the messaging, labeling them as good and bad – it’s also about the science. Take a look at the food groupings again:

As you can see from my highlighting in the table above, the NOVA scheme puts meat in a category (unprocessed) with the healthiest foods. Conversely, plant-based meat substitutes are grouped together with some of the unhealthiest foods. This grouping will greatly impact how meat and plant-based substitutes look in nutritional studies – meat will look better and the plant-based alternatives will look worse. (The same goes for dairy versus plant-based dairy.)

One could hardly devise a better system to make meat and dairy look good and meat and dairy substitutes look bad. It delivers an official good-versus-bad messaging in an authoritative, scientific voice and, to boot, the specific food grouping actually makes them look good and bad, respectively, in nutritional studies.

It’s a testament to the genius of this idea that it has been so widely accepted and rarely questioned.* Even your favorite liberal news sources are pointing out, on a regular basis, that UPF includes meat substitutes! (It’s an irresistible clickbait opportunity for lazy editors.)

*Prof. Astrup’s comments above are the closest I’ve seen to anyone pointing out that the current conversation on UPF is very bad news for climate change.

Whether or not the NOVA system, or any reporting on it, intentionally supports the meat industry, there’s no doubt that the meat industry benefits from it.

Last month, I outlined the war over the most critical ethical dilemma (beef versus legumes), mentioning two other strategies that are relevant here too:

- The amount of state funding to the meat industry eclipses that to plant-based food industries by huge amounts (1200 and 900 times larger, respectively, in the EU and US). Brazil, being the largest exporter of beef in the world, is unlikely to be any better.

- Industry groups such as the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association (NCBA) are very active in generating content online that promotes their product. The NCBA has a Masters of Beef Advocacy program (not an actual master’s) that trains content creators in influencing public opinion in favor of beef.

Moving on, I want to take a closer look at the decision to classify soy-based products like tofu and tempeh as UPF while meat is considered to be unprocessed.

Meat vs. Tofu: which is more processed?

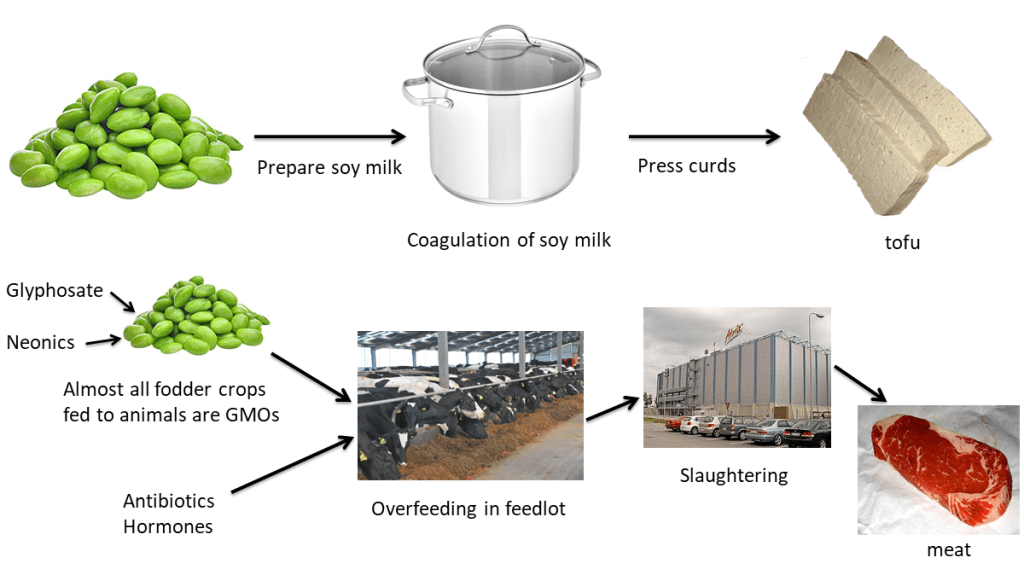

Tofu has been around for more than a millennium, possibly as much as 2000 years, and is quite simple to make. Soy milk, prepared from soybeans, is coagulated and then pressed into cakes. It spread throughout Asia with the spread of Buddhism as tofu was an important protein source for vegetarian Buddhist monks. Eventually it made it the US (the first US tofu company was established in 1878) and the rest of the world.

The method for making tofu is quite similar to that for making a basic cheese, such as cottage cheese. Most cheeses involve additional steps such as mold ripening and ageing and are therefore actually more complicated that tofu. And yet tofu is considered to be an ultra-processed food, while cheese is not. Then there’s meat, which NOVA classifies as unprocessed. Considering everything that goes into producing meat, how can this be?

I’ve simplified the processes shown above, but a description of the entire process would look even uglier for meat. It’s not long since we had BSE (mad cow disease), caused by feeding ground up animal carcasses to cows (which are herbivores). Even today, feeding of manure and chicken litter to cows is considered acceptable – think about that for a moment. Of course, choosing organic and pasture-raised meat is a better option, but the fact is that most meat and dairy consumed in the world comes from conventional industrial operations.

The entire process behind a food product should be considered – to call meat unprocessed because nothing is done to it after butchering is ridiculous. To classify tofu as ultra-processed is even more so.

(Aside: Buddhists choose tofu instead of meat to reduce suffering in the world. The suffering that animals endure during their cramped lives and traumatic deaths should be considered as part of the equation too. You are what you eat.)

What about more processed meat and dairy substitutes?

Of course, an item like a vegan chicken nugget is more processed than tofu. But personally, if I cook something like vegan chicken tenders, I’ll usually have some veggies to go with it – spinach sautéed with garlic, for example. Meat substitutes are designed to replace meat, not veggies, and that’s how we should evaluate them. Studies have demonstrated that processed meat substitutes are healthier for your heart than the meat that they replace – and these are actually controlled trials, not observational studies.

Of course, fresh veggies and fruit should occupy a large portion of our diet and I believe that cooking is one of the best forms of activism. At the same time, processed plant-based food has a very important place in the world. To help people reduce meat consumption (this is our most critical action, as consumers) we need tastier alternatives.

We’ve always had the option of following a whole-food, plant-based diet, but clearly that’s not for everyone. It’s much easier to ask a person who’s used to cooking a beef burger or chicken nuggets for dinner to switch to modern plant-based substitutes that are cooked the same way and taste as good.

The number of people adopting plant-based diets has increased considerably with the improvement in the taste and texture of plant-based food products. But this has been jeopardized as the narrative on UPF is co-opted by the meat and dairy industries. Their message is that you should feel free to go vegetarian or vegan as long as you don’t eat meat and dairy substitutes. Don’t get suckered into believing this.

If you’re interested in ethical consumption, climate change, food sustainability, and plant-based food, pop on over to my other blog, Ethical Bargains.

Discover more from The Green Stars Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.